East Africa’s manufacturers hit by costs and imports

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

For Navalayo Osembo, the “Made in Kenya” tags on the running shoes her company produces are a hard-won source of pride.

“It has been an extremely difficult job,” says the founder and chief executive of Enda, the first manufacturer of professional running shoes in Africa. “I was saying: ‘I want to create this product, there’s no infrastructure to create it, there’s no skillset to create it.’”

Enda — Swahili for “go” — started out in 2017 making whole shoes in China. But it has since moved much of the work to Kenya. Depending on the model, between 40 and 80 per cent of work is now done in the country, which is home to some of the world’s greatest runners.

But after six successful years — taking annual production to 24,000 pairs of trainers, creating 80 direct and 2,500 indirect jobs in Kenya — Osembo is considering outsourcing most production to China again, leaving only the design and marketing in Kenya. “I think we can be a Kenyan brand without necessarily being made in Kenya, because the business has to survive,” she explains.

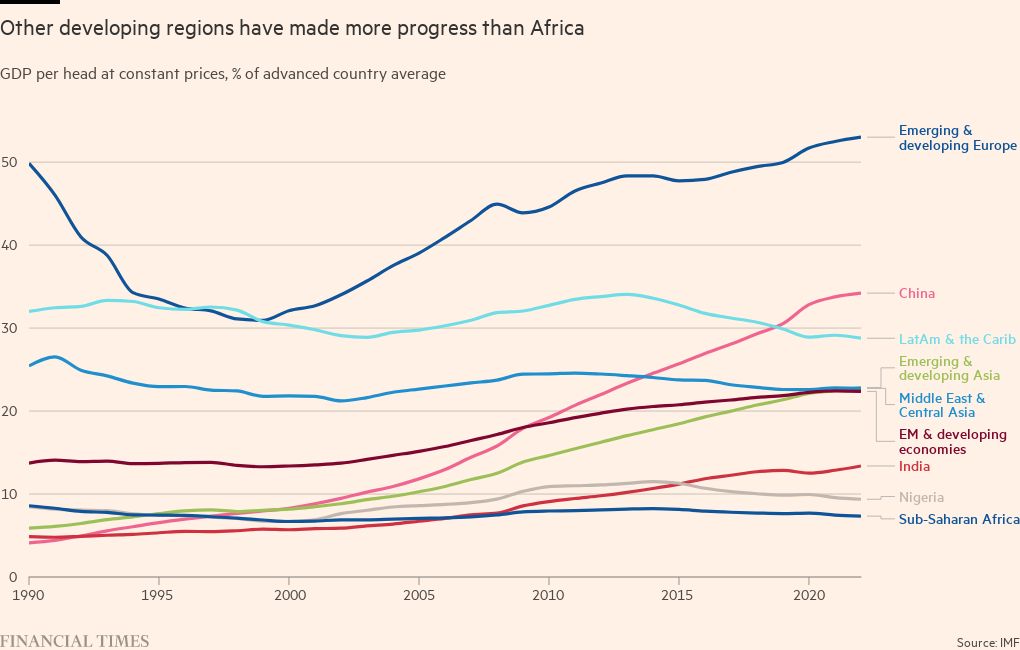

Many countries globally have pursued economic development through manufacturing and exports. In east Africa, for example, Kenya, Ethiopia and Rwanda have all sought to emulate approaches taken by South Korea or Mexico.

However, manufacturing has recently gone backwards in many African countries, as local producers such as Osembo face being overwhelmed by rising costs, infrastructure problems that hamper logistics, high energy prices, unreliable power grids, tax and customs burdens, as well as cheap Chinese imports.

In Kenya — despite the country’s reputation as a freewheeling business environment — manufacturing has struggled to sustain a transformative rate of growth. As a sector, its share of GDP almost halved from a peak of 13 per cent in 2007 to 7 per cent in 2021, according to the World Bank.

Osembo cites high import taxes on supplies, customs bureaucracy and supply chain disruption among reasons to move manufacturing to Asia: “I am such a big believer in development, but also from a practical perspective, I need to be able to plug in the global supply chains.”

Rajan Shah, chair of the Kenya Association of Manufacturers and of Capwell Industries, a food processor, says that “low competitiveness, regulatory burden, and then tax unpredictability are probably the three major challenges”.

He says corporate taxes and levies raise manufacturing costs by about 45 per cent. “If you compare that with other developed economies, that’s probably where they are — but, in a developing economy, where we are still building a middle-income class, it’s high.”

In some countries, such as Rwanda — where, four years ago, Volkswagen rolled out the country’s first domestically built car — manufacturing has gained ground. Nevertheless, it still represents just 12 per cent of GDP across sub-Saharan Africa, according to World Bank data. That compares with 16 per cent in Latin America and 15 per cent in South Asia.

A growing specialised workforce and a focus on renewable energies offer fresh advantages, however. Roam, founded by Swedish entrepreneurs in Kenya, has launched an electric motorcycle and bus made in Nairobi and developed alongside Kenyan engineers. For the motorbike, sophisticated components including the power train and batteries are imported from China and India, but other parts are made locally.

William Ruto, Kenya’s president-elect, has told the Financial Times he wants to boost manufacturing, especially the textile and leather sectors, as his country imports most fabrics, including the local kitenge staple, from Asia. “We can produce that in Kenya with our cotton farmers,” he says. “Strong manufacturing also goes along the chain of leather — we’re talking about the whole chain from production all the way to value addition and manufacturing at the very end.”

In Ethiopia, since 2016, manufacturing has been underpinned by a garment sector fuelled by state-led investments. To develop a strong textile and leather sector, Ethiopia built industrial parks able to manufacture at lower costs. This initially attracted global investors such as PVH Corporation, owner of the Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger brands.

But local inefficiencies and political uncertainty spilled over into manufacturing. In November, PVH closed a facility in Ethiopia, transitioning to a local manufacturing partner, soon after the country lost duty-free access to the US over the conflict in the Tigray region.

“Behavioural response from investors and buyers that are sourcing in Ethiopia is one of the challenges,” says Ethiopia’s industry minister, Melaku Alebel. “Buyers are choosing to place new orders outside Ethiopia, investors have temporarily scaled back operations, and manufacturers like PVH have exited.”

He says the government is negotiating with the US, and believes the African Continental Free Trade Agreement offers a “new opportunity”. Analysts say it could establish Africa as a global manufacturing centre and smooth cross -border trade.

“It is often cheaper to import from China,” says Landry Signé, a Cameroonian senior fellow in the Africa Growth Initiative at the Brookings Institution. But he adds: “Trading between African countries will contribute to unlock Africa’s manufacturing potential.”

Comments