Nigeria and Ghana’s health systems stand in contrast

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

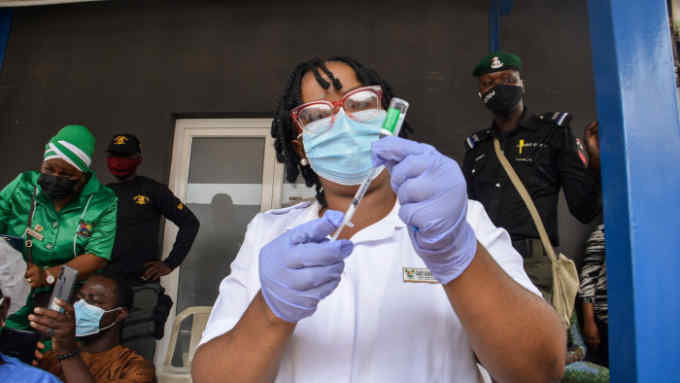

When Covid-19 hit Nigeria in early 2020, there were fears its chronically understaffed healthcare system would be overwhelmed. Frustrated by the pay and conditions, many of its most qualified workers had left for better opportunities abroad.

Yet, while Nigeria ended up avoiding the worst predictions for the pandemic — thanks to a young population with a median age of 18 — the country still has some of the worst health outcomes in the world.

Life expectancy in Nigeria is just 55, the fourth lowest in the world. The country has the highest mortality rate among under-fives and is the most dangerous place for pregnant women: Nigeria accounts for 20 per cent of all deaths related to pregnancy and childbirth worldwide, according to the World Health Organization, despite having 2.6 per cent of the global population.

The Nigerian government says it has already implemented some of the reforms highlighted in a recent report in The Lancet health journal and “will carefully consider” other recommendations as it seeks to improve health outcomes for its 206mn people. The WHO says the absence of affordable treatment and delays in accessing adequate healthcare are the principal reasons for Nigeria’s high maternal mortality rate.

Childbirth is perilous in the country’s rural areas, where poverty and poor health infrastructure exacerbate an already risky environment for pregnant women, says Abiodun Adereni, founder of HelpMum, a health start-up working to reduce maternal mortality in Nigeria.

Adereni says pregnant women should be encouraged to seek help from qualified healthcare workers in their communities. “Mothers should not be having deliveries with untrained personnel and that’s why it’s important for them to understand that, if they go to quack workers, they’re putting their health in danger,” he says.

In Nigeria, 917 women die per 100,000 live births and 72 babies die per 1,000 live births. That compares with 308 and 33 respectively in Ghana, where people on average live nine years longer than in Nigeria.

Ghana has a much smaller population than Nigeria, but a similar gross domestic product per capita at about $2,400. However, its government has been able to deliver better healthcare because it has a more holistic approach to provision, says Ibrahim Abubakar, a professor of infectious diseases epidemiology at University College London and chair of the commission that produced the Lancet report.

“Quality healthcare is the whole package,” he says. “Quality of staff in the health centres, medicines, supply chains to provide authentic medicines, recording of information, data systems, and training of healthcare workers.”

Ghana provides subsidised primary healthcare via a national service, launched in 2003, which gives roughly 40 per cent of its citizens access to routine treatments — such as antimalarial drugs.

Peter Hawkins, the Unicef representative in Nigeria, says government funding at all levels must increase to enable primary healthcare to keep up with the growing population, especially in rural areas, where health services are sometimes non-existent.

“Eighty per cent of [health] issues could be resolved or prevented at the primary healthcare system but many people go straight to secondary or tertiary hospitals,” Hawkins says. “The investment is disproportionate to the impact. That needs to be addressed.”

Only a handful of African countries meet the WHO-recommended ratio of 10 doctors per 10,000 people. For Nigeria and Ghana, the figures are 3.8 and 1.7 respectively. Both countries committed 15 per cent of national budgets to healthcare spending as part of the African Union’s Abuja declaration in 2001. But Nigeria earmarked only 5 per cent for health in its most recent budget while Ghana allocated 7.6 per cent of its 2022 budget to health spending.

Almost 70 per cent of the population in Ghana have some form of health insurance, either through the national health programme or private schemes that can be afforded by the country’s middle class. That compares with only about 20 per cent in Nigeria who have health cover to defray treatment costs. A 2012 study found that Ghana’s national insurance scheme increased access to the formal healthcare sector.

And, for 1.5mn of its poorest citizens, Ghana provides direct monthly cash transfers worth about $20 to cover healthcare costs. Nigeria has a similar project covering 8mn people that equates to $12 a month but, crucially, Ghana provides insurance in addition to the cash transfer. This ensures that far fewer Ghanaians have to pay for primary healthcare costs themselves.

Nigeria’s government must boost healthcare spending at all levels and provide a national insurance programme for its poorest citizens, argues Abubakar — while also ensuring there is accountability for the money already being spent.

“It’s in the interest of health and other sectors that fiscal spending increases and is used responsibly,” he says.

Comments