Africa’s search for lasting route out of poverty proves elusive

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When KY Amoako was growing up in 1950s Ghana, he hung on every word of Kwame Nkrumah, the liberation leader and, later, the country’s first prime minister and president. Amoako, who spent a lifetime working in “development”, remembers the heady feelings that Nkrumah inspired in a young man whose country and continent were on the verge of throwing off colonial oppression.

“Africa was going to be prosperous, strong, united, and respected,” he wrote of Nkrumah’s project to “raise up the lives of our people” in what would become 54 independent nations.

Amoako built a career at the World Bank in the 1970s and became head of the UN Economic Commission for Africa — two institutions he believed could help realise Nkrumah’s vision. Writing in his memoir some five decades later, he was clearly disappointed: “So why is Africa still poor?” he asked.

The answer to that question is complex and disputed. Much research points to factors such as poor leadership, weak institutions, corruption, and lack of infrastructure. But these proximate causes fail to explain why those elements are present or lacking — and why similar obstacles have been at least partially overcome elsewhere, particularly in Asia.

The depredations of the transatlantic slave trade and the short, brutal history of European colonialism go some way to explaining subsequent disappointments. New countries with random borders struggled to build modern nation states and to break free of the extractive economic models they had inherited.

Yet such analysis goes only so far. As Stefan Dercon, professor in development economics at Oxford university and author of Gambling on Development, says: “The only lesson here is: get a better history.” The key to breaking free, he argues, is what he calls an “elite bargain” in which those who control the levers (and wealth) of their new states agree to roll the dice in favour of development and expanding economic opportunity.

In Dercon’s view, development is primarily a matter for countries themselves. Outside assistance in the form of overseas development aid, loans, or technical transfer can only play a peripheral role, he says, bolstering nation-building projects that are already under way. In some cases, he argues, overseas assistance can warp incentives and actually do damage.

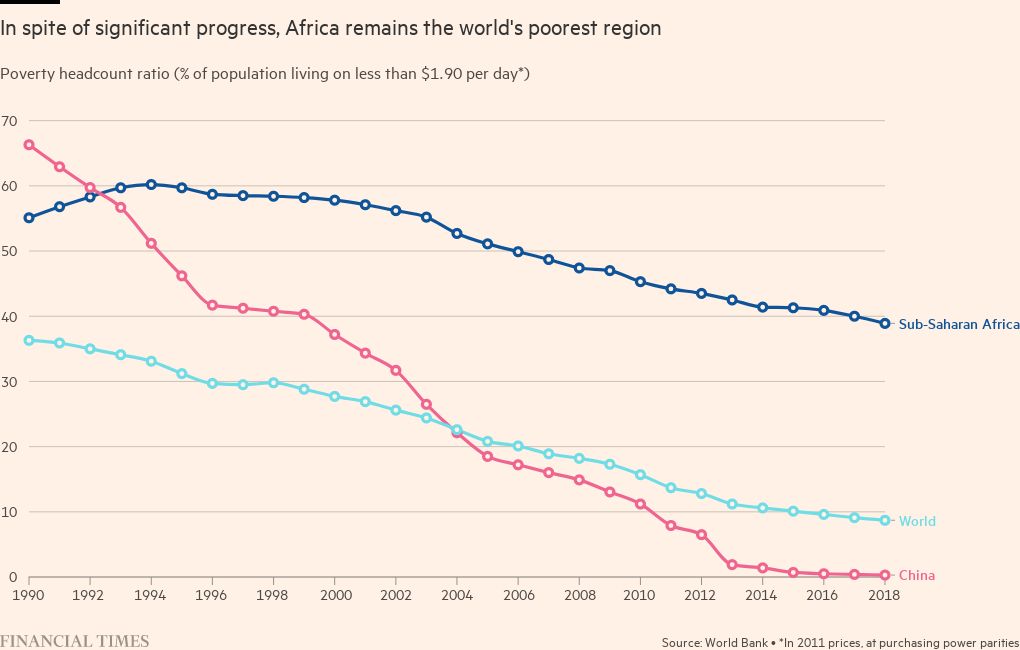

Whatever the reasons, Africa remains the world’s poorest continent by almost any measure — a picture that did not seem inevitable when leaders like Nkrumah were fighting for independence.

According to the World Bank, in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms, which adjusts for local costs, oil-rich Equatorial Guinea, at $18,000, has the highest per capita income of any continental African country, though highly unequal distribution renders that figure near meaningless. The poorest country is the Central African Republic which, along with others such as South Sudan, Niger and the Democratic Republic of Congo, barely clear income levels of $1,000 per capita.

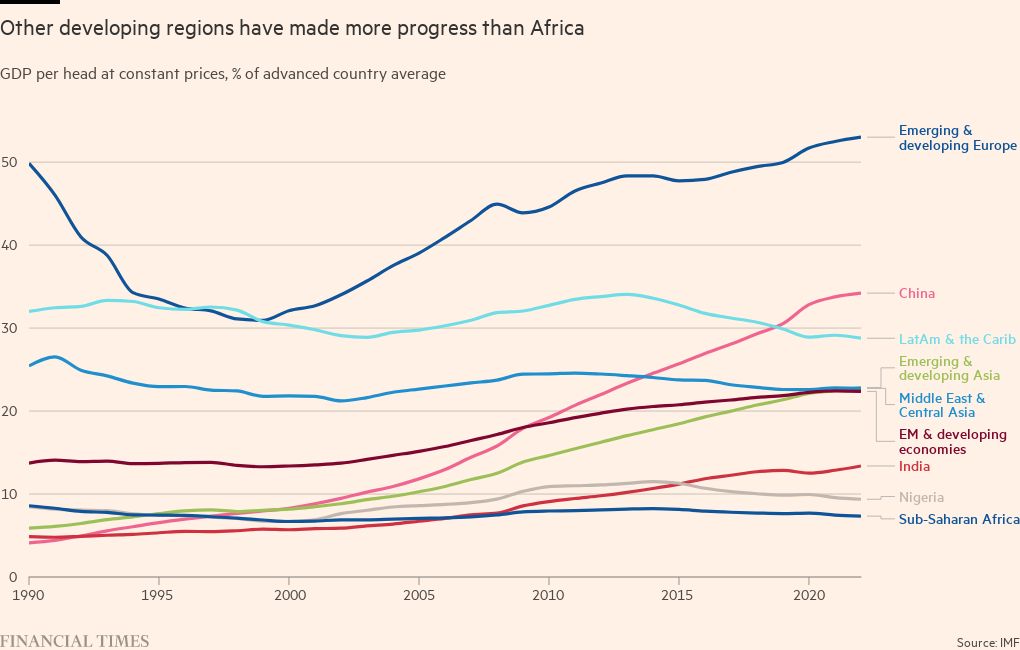

To take another measure, the average gross domestic product per capita in sub-Saharan Africa, again in PPP terms, is $4,120. But that compares with south Asia’s $7,000, east Asia’s $20,300, and a world average of $18,700. Nkrumah’s Ghana, though a relative African success story, is often contrasted unfavourably with South Korea — which was equally poor at independence but now has a per capita income of $47,000, making it nearly eight times richer.

“From that point of view, African development has been disappointing,” says Akihiko Tanaka, president of the Japan International Cooperation Agency, which administers Tokyo’s overseas development budget. “But, since the beginning of the 21st century, many sub-Saharan countries have registered quite significant economic growth, with a 5-6 per cent growth rate fairly common.” Growth, Tanaka adds, is not the sole measure of success, though it helps to raise tax and improve services.

“Development is the expansion of freedom,” he says, referring to the definition of Amartya Sen, the Indian Nobel Prize-winning economist. Sen has argued that the definition of success is when people can live their lives as they please, not as poverty or other constraints dictate.

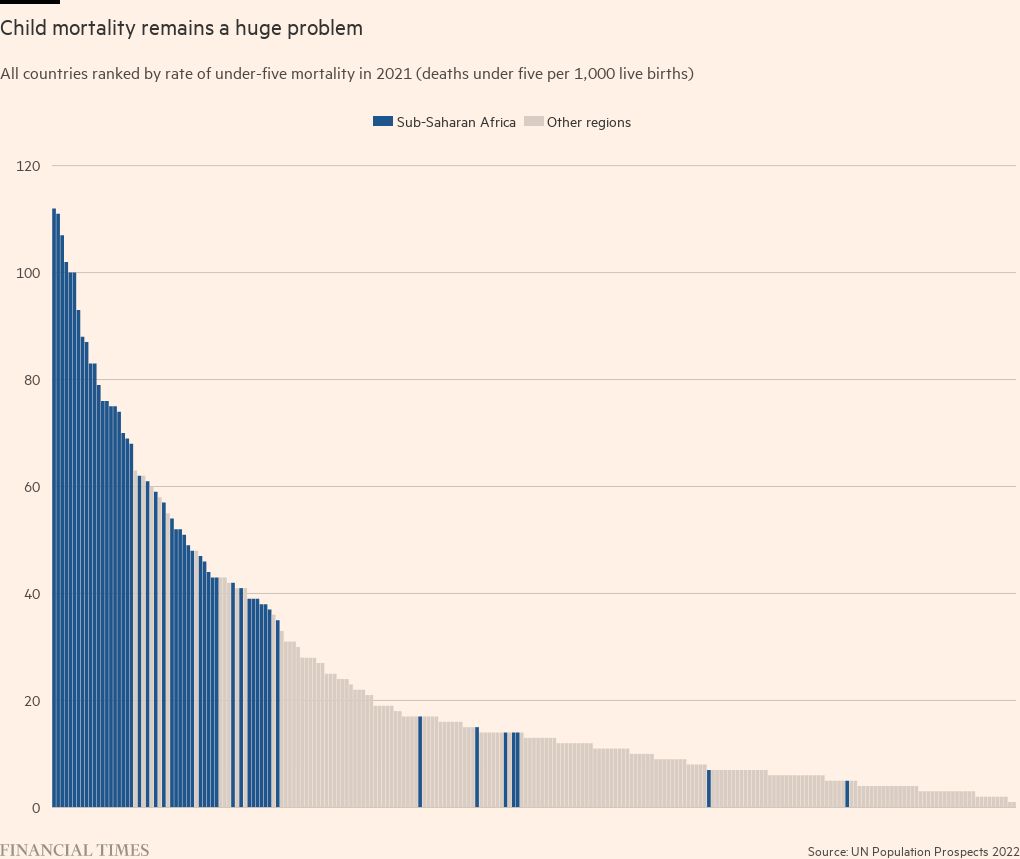

By this measure, some progress has been made. In August, the World Health Organization reported that healthy life expectancy in Africa had risen by a remarkable 10 years since 2000. At 56, it is still eight years below the global average, but it has caught up five years since 2000, an indication that some countries may have turned a corner.

Among the new factors in that time are improved democratic accountability, debt forgiveness and the arrival of new investors, notably China.

This rise in healthy life expectancy — and other improved indicators, such as big falls in child and maternal mortality — are described by Matshidiso Moeti, WHO regional director for Africa, as “testament to the region’s drive for improved health and wellbeing of the population”.

But such development gains, she warned at a recent conference, were now being threatened by multiple shocks. The Covid pandemic damaged health programmes, closed schools and squeezed economies, while the war in Ukraine has sharply raised food prices. “Progress must not stall,” she said.

A further threat to progress, however, is a lower appetite among some richer countries, the UK chief among them, to provide development aid. Although experts such as Dercon argue that external assistance plays only a marginal role in development, in areas like health it has had an outsized impact.

Foreign governments, multilateral institutions, and private organisations, such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, have funded vaccination and anti-malaria campaigns, provided antiretroviral medicines for HIV patients, and helped build bottom-up health services in many countries.

Organisations such as the UN World Food Programme have provided essential food aid in regions including the Horn of Africa, the Sahel, and Madagascar, where a three-year drought has badly affected the south of the country.

But while the assistance has helped stave off crisis, it has not had a lasting impact, says Lalaina Rakotondramanana, prefect of Ambovombe in Madagascar’s south. “We don’t need emergency support any more, we need development,” he says, noting that international agencies have pumped billions of dollars into Madagascar in the past 30 years. “Where has that money gone?”

A suspicion that international assistance may be wasted has allowed the UK to cut its development pledge from 0.7 per cent of gross national income (GNI) to 0.5 per cent with little public outcry. In July, the British government blocked non-essential development payments on concerns that the cost of relief work would breach that lower spending cap.

Advocates of development assistance fear the UK is setting a dangerous precedent. Japan, which is organising the Tokyo International Conference on African Development in Tunisia in August, spends 0.34 per cent of GNI on overseas development assistance, according to Tanaka of JICA — a sum he would like to increase. “Now the UK has decided to do this, I worry if those anti-ODA [official development assistance] people could use this as an excuse to not to agree on the expansion of development co-operation,” he says. “I hope that others will not follow the UK.”

Under Emmanuel Macron, France has been edging in the opposite direction, seeking to raise the proportion of money it spends. “France has probably surpassed the UK government with 0.55 per cent of our [gross national income] in ODA,” says Rémy Rioux, president of the French Development Agency, a government-owned financial institution.

Of Paris’s push to bolster assistance to Niger, a poor country that is threatened by growing insecurity, Rioux says: “The work of development is to identify something we can support. It is not about decrees from outside. It is: do we have the tools to unlock the dynamism and positive developments in the countries themselves?”

Not long before he died, Kofi Annan, former UN secretary-general, told the FT: “I think aid is important, but no nation can expect to develop on the basis of assistance from outside. My own view is that Africans would prefer to stand on their own.”

Comments