Pandemic sets Africa’s sights on vaccine independence

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

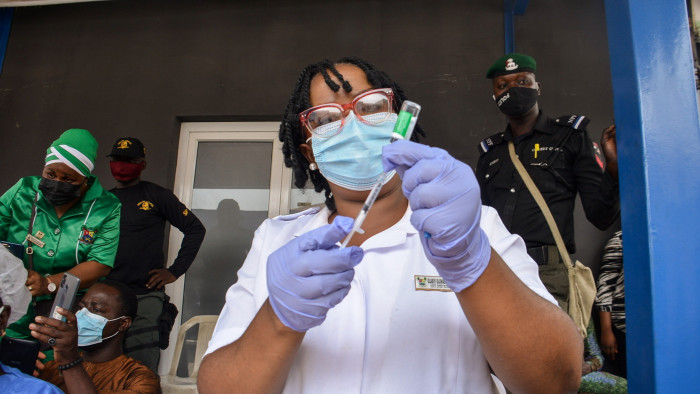

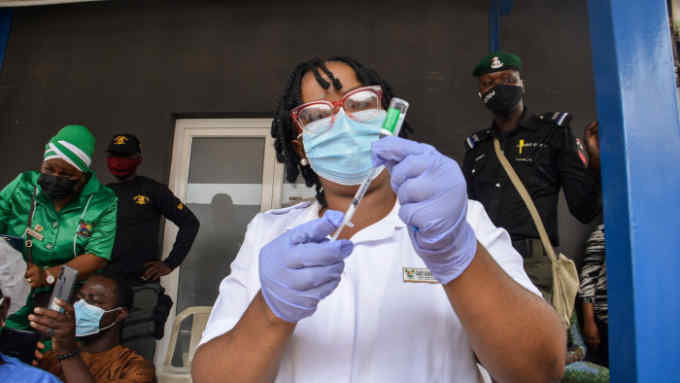

It was John Nkengasong who first saw the opportunity presented by the Covid-19 crisis. In early 2021, the then director of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention was boiling over with frustration that, as vaccines were being rolled out across the world, African nations found themselves at the back of the queue.

“We consume 25 per cent of the world’s vaccines,” he says, referring to the shots for diseases ranging from measles and whooping cough to tuberculosis and rotavirus, a cause of potentially life-threatening diarrhoea. “Yet only 1 per cent of vaccines are manufactured on this continent.”

He could see how that made African healthcare systems painfully dependent on overseas entities. Drug companies such as Pfizer and Moderna, operating on a largely commercial basis, were shipping most of their jabs to the US and Europe. Covax, the World Health Organization-backed facility for low- and middle-income countries, was heavily reliant on a single supplier, the Serum Institute of India, which was producing the AstraZeneca vaccine.

When, in March 2021, Serum announced that it was halting exports following a dramatic upsurge of Covid cases in India, Nkengasong warned: “The vaccine landscape is extremely challenging for our continent.” It was, in effect, restricting the choice of medical tools that African health authorities could deploy amid the pandemic — and when. “Basically, we have to go to war with what we have,” he said at the time.

Nkengasong’s proposal — one that has rapidly gained political traction — was that Africans should sharply increase the amount of vaccines produced on the continent. “We need to develop a road map and a framework for Africa’s vaccine manufacturing,” he says now, adding that the continent ought to be meeting 60 per cent of its own needs by 2040.

There are already some centres of excellence — including the Pasteur Institute in Dakar, which produces the yellow fever jab, and Aspen Pharmacare, a South African drug manufacturer that has a licence to produce hundreds of millions of doses of Johnson & Johnson’s one-shot Covid jab.

Salim Abdool Karim, a South African infectious disease expert, says these examples disprove the common assumption that Africa lacks the physical infrastructure or scientific base to produce existing or even new vaccines. In his own field of HIV research, he says, laboratories in Africa have made several breakthroughs. “Let’s just explode those myths — Africa is highly capable of doing laboratory science,” he says.

Paul Kagame, president of Rwanda, has backed the plan, persuading BioNTech, the German biotech company that co-developed the first mRNA vaccine against Covid-19, to build a plant in Kigali. The company broke ground in the Rwandan capital in June and is planning another facility in Senegal.

Moderna, which also developed an mRNA jab against Covid, is investing $500mn in a plant in Kenya to manufacture vaccines based on the same technology. And, last month, South African biotech company Afrigen announced a collaboration with the US National Institutes of Health, whose technology underpinned the mRNA vaccines, to develop jabs for other diseases. The partnership with the NIH includes developing potential vaccine candidates against HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, influenza and other diseases prevalent in Africa.

Professor Trudie Lang, head of the Global Health Network at the University of Oxford, says the beauty of the new generation of vaccines is that they can be easily adapted to other diseases. So called “plug and play” technology — in which the genetic code of a virus is used to teach the body to fight an infection — means that, in theory, the vaccine platform can be quickly applied to new infections, she explains.

Stavros Nicolaou, head of strategic trade at Aspen Pharmacare, welcomes the manufacturing initiative but says it will not be easy. If vaccines cannot be produced at scale, he warns, they will be more expensive. Buyers, including governments and international organisations such as the vaccine alliance Gavi, will need to commit to buying African-produced medicines in bulk, he argues.

However, even in the middle of the Covid pandemic, which set back health campaigns badly as resources were diverted, the power of vaccines was demonstrated.

Last year, the WHO backed the widespread use of Mosquirix, a malaria vaccine produced by GSK that helps prevent a disease that killed more than 400,000 people, two-thirds of them under five, in 2019 alone. Several others, including BioNTech and Oxford university, are working on malaria vaccines that may prove even more effective and easier to administer.

In a further vaccine breakthrough, the WHO announced last year that wild polio, which can cause crippling paralysis, had been eradicated in Nigeria, and thus in the continent as a whole. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the WHO, called it “one of the greatest public health achievements of our time” — although there has since been a small recurrence of the disease in Malawi.

OB Sisay, a senior adviser to the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, says Africa has no choice but to develop greater self-sufficiency following the experience of the pandemic.

Despite all the fine words and good intentions, he says, “the way the world has handled Covid has not been strategic, it has not shown foresight, and it has not been collaborative.”

Comments