Ben Sakoguchi’s art from America’s concentration camps

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

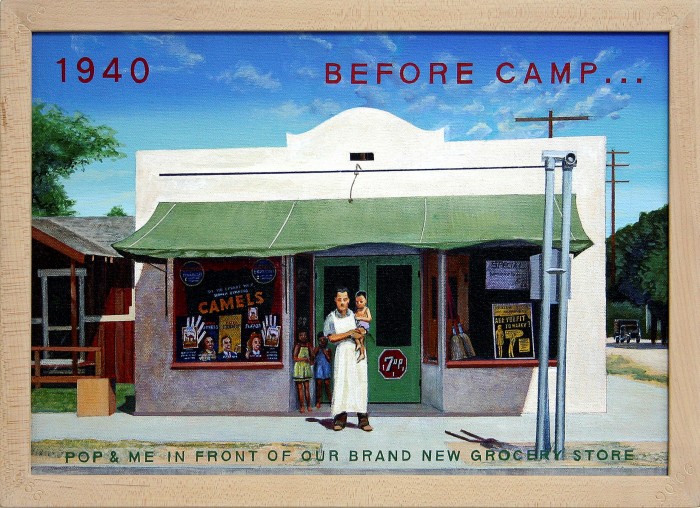

“Pop & me in front of our brand new grocery store,” reads the inscription on a small acrylic painting, part of Ben Sakoguchi’s multi-panel “Postcards from Camp” (1999-2001). In the picture, a man in a long white apron holds a toddler in front of a neat shopfront underneath the date of the scene, 1940, and the ominous words “Before camp . . . ”

The photograph on which this painting is based was taken in San Bernardino, a city about 60 miles inland from Los Angeles. Sakoguchi’s family had settled there, in a predominantly Hispanic neighbourhood, after his parents got married. Because he was born in Japan, however, Sakoguchi’s father was not allowed to own property in California; the store was in the name of Sakoguchi’s Japanese-American mother, Mary.

Two years later, following the declaration of war between the US and Japan, Sakoguchi’s parents and older siblings were forcibly relocated to Poston, Arizona, where they were incarcerated along with more than 17,000 other people with Japanese ancestry in a hastily constructed concentration camp. The three-year-old Ben and his baby sister both had measles at the time, so were held back, terrified and alone, in the county hospital until they recovered.

This period in American history is the subject of “Towers” (2014), a 17-panel assemblage of acrylic paintings by Sakoguchi presented by Bel Ami gallery in the Focus section of Frieze Los Angeles. Curated by Amanda Hunt of the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, Focus is part of the fair dedicated to younger LA galleries and the city’s “emerging art scene”.

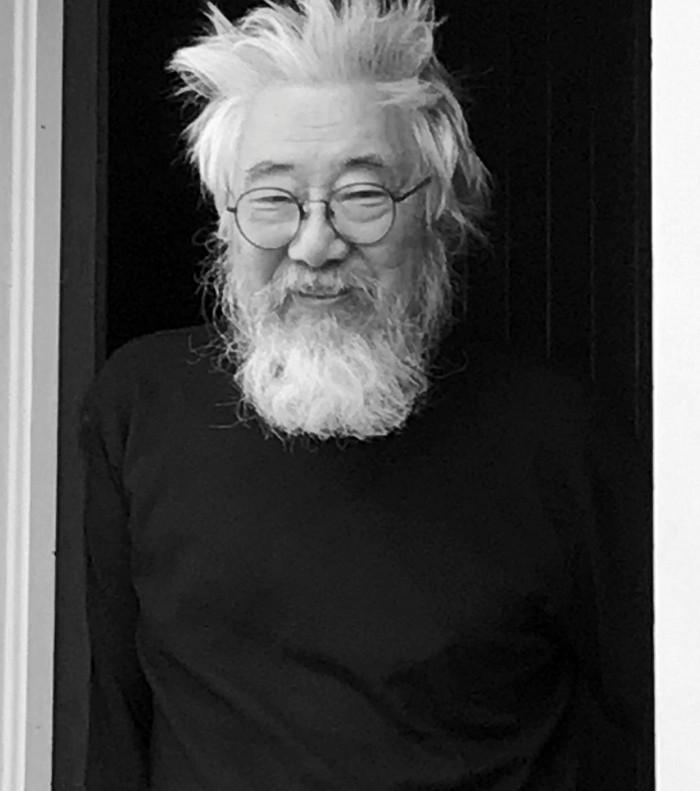

Pasadena-based Sakoguchi is now 83 years old and has been painting all his life. After his first LA gallery Ceeje closed in 1970, he retreated from the commercial art world, focusing instead on his career teaching painting at Pasadena City College. His work became known to many Angelenos only recently, following his exhibition in 2018 at the artist-run space Potts and his widely reviewed debut show with Bel Ami, Chinatown, in 2021.

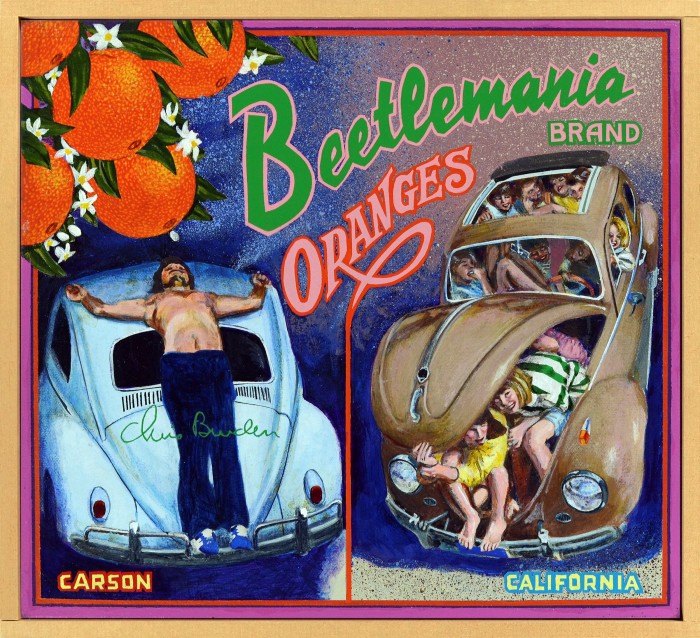

Viewers familiar with Sakoguchi’s painfully dark sense of humour might peer into the 17 detailed panels of “Towers” and look for the kinds of visual and verbal jokes that punctuate many of his other paintings. Each of his long-running Orange Crate Label series, for example, is based on the amalgamation of a fictional brand’s logo, a California place name and a pseudo-promotional image, often surreal, ironic, political or all three. Beetlemania brand oranges are advertised with the photo of performance artist Chris Burden crucified on the bonnet of a Volkswagen Beetle and come from Carson (get it?). Hoax brand oranges — illustrated with the spiky orange SARS-COV-2 virus — come from Corona. Napalm oranges come from Firebaugh.

In “Towers”, which documents the 10 “relocation centres” in which Japanese-Americans were forcibly detained during the second world war, there are no jokes, save for Sakoguchi’s wince-inducing, ironic appropriation of the slur “Jap”. “No Japs Allowed,” reads a thick black inscription on a map of the US, following a wide orange strip of the West Coast from Mexico to Canada. Elsewhere: “Military necessity: Remove 120,000 Japs from the West Coast and put them in inland concentration camps. Military logic: Keep 160,000 Japs in place on the Hawaiian Islands over 2,000 miles out in the Pacific Ocean as a military necessity.”

Sakoguchi no longer gives interviews, but in a video recorded in 2016 he reflected on the cruelty and injustice of the Japanese internment programme. The water towers that gave his piece its title, Sakoguchi explained, were ubiquitous because these camps were all established in desolate places with no existing water supply, “where nobody wanted to live!”

Traditional family bonds were strained to breaking point, with meals taken en masse in mess halls and ablutions made in communal toilet blocks. “We were wild kids,” Sakoguchi remembered. He attributed to the three years he spent in Poston his life-long sense of independence, but also his sense of not belonging.

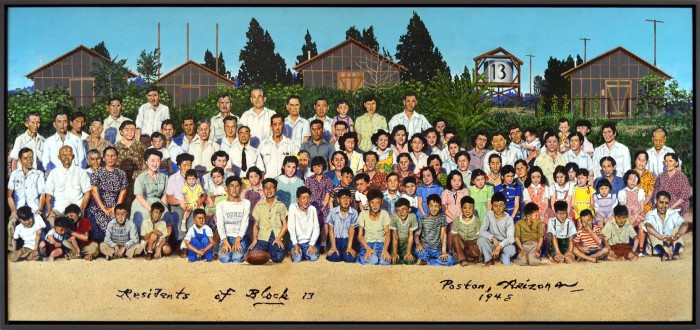

At the centre of “Towers” is a large painting copied from a photograph taken in 1945 of the residents of Poston’s Block 13. The young artist kneels in the front row; behind the group we can glimpse the flimsy tarpaper barracks. Never again in his life would Sakoguchi be surrounded by so many Japanese Americans. It was a grotesque parody of community, but also one that would indelibly shape his identity.

“People forget how it was,” Sakoguchi said in another video interview, from 2011. He recalled the bonds that were formed in the camp, but also the racism that greeted Japanese Americans when they tried to re-enter their former lives after the war ended. “Those of us who lived it remember how mean people can be,” he said. “Also how beautiful people can be.” In unflinching artworks such as “Towers” and “Postcards from Camp”, Sakoguchi takes his stand against forgetting.

Letter in response to this article:

How Japanese-American internees set medal record / From Christopher Lavender, Hong Kong

Comments