Pippa Garner’s gender-bending satire on America’s consumer culture

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

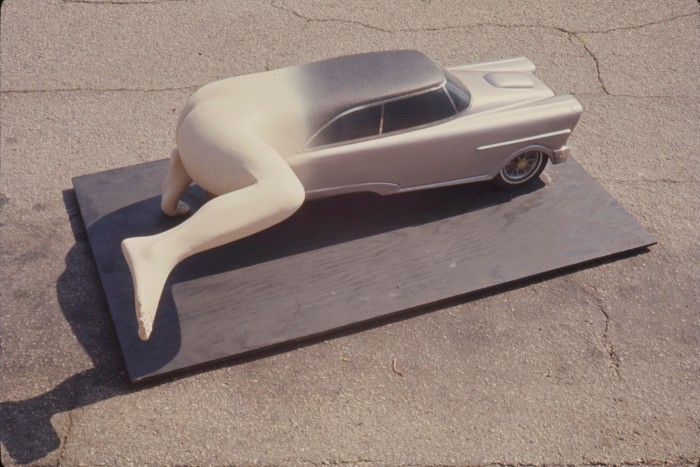

In the suffocating sprawl of America’s postwar normativity, artist Pippa Garner’s interventions made more than a few people look twice. A 1973 issue of Esquire magazine featured a car apparently rocketing backwards down the freeway — in fact a ’59 Chevy with the body reversed, its teardrop top and space-age fins turned against the flow of traffic. Two decades later, alongside blurbs for “Outrageous Beauty” and “Topless 38DD”, a personal ad she placed in the SF Weekly promoted a “Transsexual Sandwich”: “Post-op (I did it for art), Amazon blonde, beautiful, athletic, sophisticated, attracted to myself and others of my ilk”.

The inventions of Garner, manifested as performances, sculptures, drawings, videos, T-shirts and hybrids thereof, are satires on the consumer culture of America’s golden era — a time when heavy, fishlike cars plied the fresh asphalt, tinkerers could make millions in their garage, men were men and women women. And while she has lately started to get recognition befitting 50 years of outside-the-box thinking, with a significant retrospective over the winter, the understanding of both society and the art establishment has been slow in coming.

Garner’s boundary-pushing extends to her own body, which she considers a vehicle like any other. “I always looked at my body as kind of a toy,” she tells me over the phone. “I looked in the mirror and I thought, I didn’t pick this. It was assigned to me to be a hunky middle-class male.” Garner began what she calls her gender hacking in the late 1980s. The transition hasn’t always been smooth. The macho, guys-and-chicks LA art world more or less disowned her after her top surgery, unable to follow such a genre-bending visionary beyond the very picture of tall, tan, California manhood. Today she sports full tattoos of a G-string and bra.

Garner was born near Chicago in 1942 and moved to Los Angeles in 1961 — the “experimental city”, as she once told Johnny Carson when a guest on his show, “a gadget in itself”. She attended classes in automotive design at Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, but after a stint in Vietnam as a combat artist (Garner suffers from leukaemia and impaired vision following exposure to Agent Orange) her work grew restless. She had the urge to antagonise the “autosexuals” in the Art Center programme with bizarre designs. When Garner turned in the “Kar-Mann (Half Human Half Car)” (1969) sculpture — the hood and front wheels of a coupe blended into the trunk and legs of a crouching man, made of fibreglass, lifting his leg in doglike urination — she was told not to return the next semester.

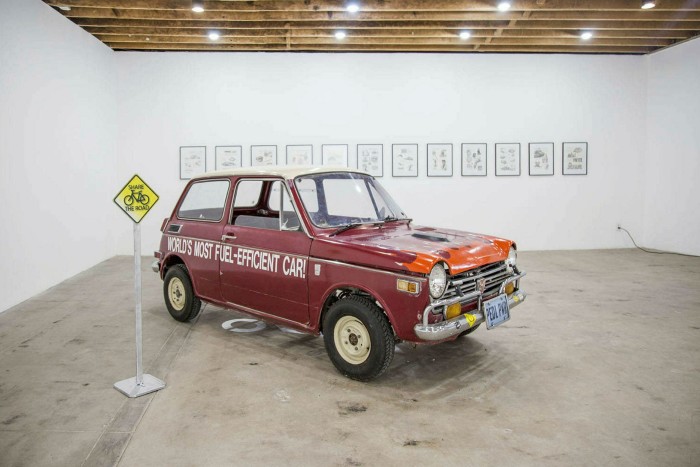

She found regular work doing illustrations and builds for magazines, support which allowed her to realise some of her zanier concepts, such as the backwards car or a front door made from car parts. While the straight art world averted its eyes, Garner earned a certain amused admiration from gear heads and car nuts. Gigs followed in Rolling Stone, Vogue and the Discovery Channel’s reality game show Monster Garage. She contributed well over 100 back-page drawings, wacky solution after essential widget, to Car and Driver. Three of her “human-powered” pedal cars have been donated to the Audrain Auto Museum in Rhode Island.

Her critique of car culture implicates the US, with all its overbuilt machines and their contradictions, not least that cars are seen as masculine but also sell sex. “Her work is about gender expansiveness and gender as a commodity,” says Fiona Duncan, a writer preparing an essay on Garner. “You can customise your body, inside and out, so long as you can afford to do so.” In winter of 2021, Joan, a non-profit space in downtown LA, presented Immaculate Misconceptions, a retrospective of five decades of Garner’s work, from her double-decker lounge chairs to a series of punny lamps (“Lampoons”) to an Electrolux vacuum smoking a cigar. Visitors could also see “Genderometer” (c1985-2021), a retro-looking dial one turns, fluidly, between Masculine and Feminine.

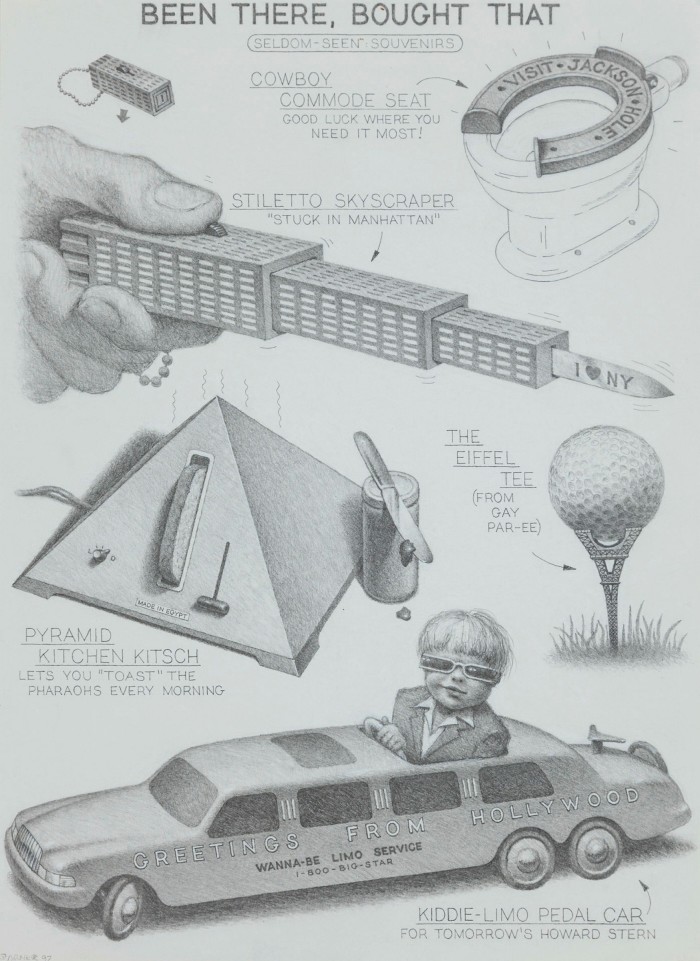

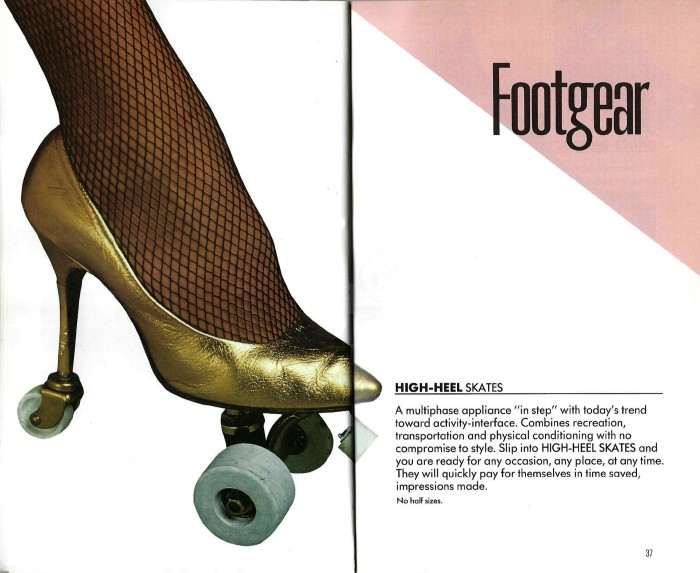

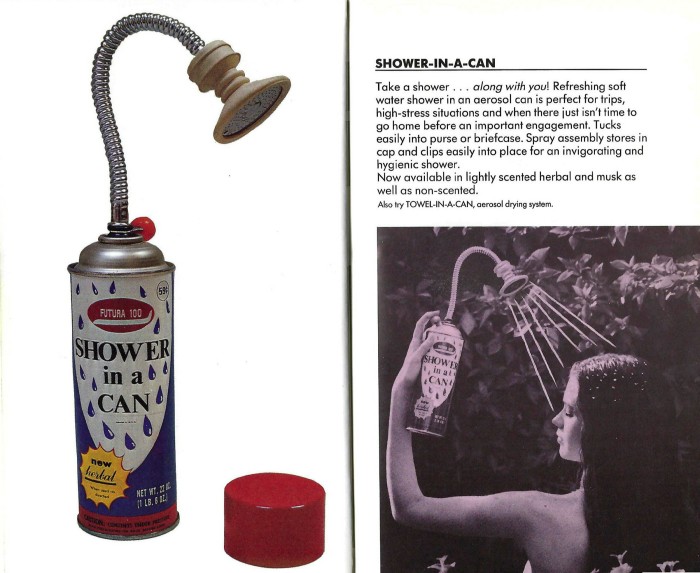

Curator and dealer Sam Parker remembers finding a copy of Garner’s “Better Living Catalog” (1982) in his parents’ library. Flipping through page after page of modern conveniences — high-heeled roller skates, an umbrella made of palm fronds, a shower-in-a-can — he circled what he wanted for Christmas. Alas, these fantastic conveniences existed only as props, part of Garner’s satirical purpose.

Years later, in 2015, Parker presented a selection of Garner’s drawings and prototypes, including the “Shower-in-a-Can”, at the Spring Break art fair in New York. “The response was insane,” says Parker: suddenly, Garner had the eye of pros such as the art journalist Linda Yablonsky and artist Maurizio Cattelan.

The exhibition sparked a wave of interest in Garner’s life and work, this time in the conventional art world. “She embodies all these paradoxes of cutting-edge thinking or living now,” says Duncan. “I think her humour especially resonates because life can seem so dire. It’s refreshing to be able to acknowledge all the heaviness and harm and not take it all on personally.” Although her career has been unconventional, it has followed the pattern of women artists not getting their due till their seventies.

Yet she remains a provocateur. Garner’s irreverence can be at odds with the more severe discourses around transgender identity and individual rights. In “Onboard Trophy Wife” (2013), Garner plays both a bride and groom, marrying herself — framing the duality of male and female as an absurd, performative ritual. As the credits roll, she holds up a picket sign: “Legalize Self-Marriage”.

“Men ran the 20th century,” says Garner. “There was no question about that.” She has watched the hard lines between categories rust and grow brittle. When she first began hormone therapy, for example, there was no widespread concept of the in-betweens of gender, and no good terms for people who lived there. As she puts it, “You had to jump over the fence.”

Now, the public discourse around trans rights has caught up. Likewise, Garner says, the boundaries between commercial and fine art, or between art and culture, seem less important. Her interventions into the symbols of Americana seem ever more potent alongside rising seas and electric cars. With her winningly dry optimism, Garner describes the joys of navigating LA by pedal car and bike. “Even if it’s a failed mission,” she says, “you still get the cardio.”

Comments