‘We are daring to invent the future’ — the generation that rewrote Africa’s story

The novelist Petina Gappah on a group of writers who put a fresh, modern vision of Africa out into the world

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

There is a photograph of Chimamanda Adichie, taken almost immediately after her novel Half of a Yellow Sun was announced as the first African winner of the Women’s Prize for Fiction (then the Orange Prize). She wears a red turban and an elegant sleeveless sheath dress and is smiling into the phone as she talks.

I am at the end of that call, having watched the ceremony from my office in Geneva. I know just when to call because in the room, feeding me live updates, is our friend, the Nigerian writer Molara Wood. It is on Molara’s phone that I speak to Chimamanda, who laughs as she says, “You got here ahead of my father, he is usually the first to call.”

She hands the phone back to Molara. We both whoop with joy.

It is June 2007.

I am two years away from publishing my first book. I am writing frenetically, reading everything, and dreaming about being published. As I take the bus home to my flat that night, filled with pride for Chimamanda’s achievement, I flash back to 2003.

At Johannesburg airport, on my way from a holiday at home in Harare, connecting on a flight to Zurich to get back to Geneva where I live and work, I buy a book from the airport bookshop. It is called Discovering Home: A Selection of Writings from the 2002 Caine Prize for African Writing. I buy it without knowing anything about the Caine Prize or many of the authors whose stories are published in the anthology. I read the book from start to finish that night; it is more compelling than the temptations of in-flight entertainment. By the time my flight lands in Zurich the next morning, my world is fuller, more hopeful, and much, much bigger.

It was in that anthology of short stories that I first read Chimamanda, Binyavanga Wainaina, Helon Habila and other writers from my continent. I read them all with a shock of recognition and a sense of wonder. Here were writers talking about studying, living and working abroad and coming home, about family fights and falling in love.

Here were the writers writing the Africa I recognised, the Africa I lived in both Geneva and Harare, the Africa of striving and ambition, of disappointment and heartache, of joy and love. The warp and woof of African lives. The kind of stories that I wanted to write; the kind of stories that, as far as I could see then, were not being published as a matter of course in London and New York.

Certainly, at this point, the story of my own patch of Africa, Zimbabwe, was the story of the white farmers who lost land in violent invasions. It was a story refracted through the lens of the writers Alexandra Fuller and Peter Godwin, whose memoirs were driving the narrative of what Zimbabwe meant to the west.

I had enjoyed their books, which were vivid and captivating, but I was deeply unsettled that this was the set narrative of my country. I had long wanted to be a writer. I had been writing all my life, but reading Fuller and Godwin gave me a new urgency, a determination to “write back”, to bring some sort of balance, to write in the black voices missing from the narrative. The problem, though, was that I didn’t know that anyone wanted to publish, let alone read, these stories I longed to write. On that flight to Zurich, I realised that I was not alone. Discovering Home showed me a continent of writers who wanted to tell the same kind of stories.

As a child and teenager at my two high schools in Chishawasha, I had read the first generation of modern African writers voraciously: books published in Heinemann’s African Writers Series by authors such as Chinua Achebe, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Cyprian Ekwensi, Nadine Gordimer, Wole Soyinka, Peter Abrahams, Dambudzo Marechera and many more.

Those early writers had taken it as their mission to write Africa into the public imagination, presenting to the world stories in which Africans were fully formed subjects with agency in their own histories. These writers were writing against a background in which Africans were presented as mute objects of colonial patronage. That early generation tackled themes as broad as the indignities of colonialism, the independence movements and the crushing disillusionment of the post-independence African state.

Later came writers such as Ben Okri, who became the first black African winner of the Booker Prize in 1991 for his transcendental novel The Famished Road. Okri’s success was important in linking the first generation to the next. The Famished Road demonstrated that not only could African writers narrate stories that went beyond the colonial condition and its aftermath, but that stories of families grappling with modernity, stories of love and loss, of spirituality and religion, stories that showed a joyful Africa even in its poverty, had an audience in the world.

When I got back to Geneva, where I worked as an international trade lawyer, I decided to get serious about my writing. I read that Chimamanda and Binyavanga had met each other on Zoetrope, an online writing community. I joined Zoetrope too. It is there that I met Molara Wood and Muthoni Garland, a writer from Kenya. We read and workshopped each other’s writing.

These friendships continued into real life, and with them came a chain reaction of more friendships — Molara knew Chimamanda, and through Molara I became acquainted with Teju Cole. When I read his column in the Nigerian newspaper NEXT, Letters to a Young Writer, it felt as if he was writing to me, egging me on. Muthoni was also friends with Binyavanga. I became obsessed with a blog called African Bullets & Honey by Martin Mbugua Kimani, now Kenya’s permanent representative at the UN. I started a blog called The World According to Gappah and Martin and I established a mutual admiration society. He invited me to a literary festival in Lamu, Kenya. It was here that I at last met Binyavanga, who generously included me in a circle of writers — among them Parselelo Kantai, Martin Kimani, David Kaiza, Billy Kahora, Jackie Lebo and Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor. To close off the circle, Binyavanga’s best friend was Chimamanda, whom I would call on Molara’s phone a few months later.

This group became the core of my ambitions as a writer. No one knew who I was, as I was just starting out, working on both a novel and a story collection. I had won a couple of prizes and published sporadically here and there. I was a mess of ideas and insecurity, gut-wrenching fear and ambition.

In these friends, I found my tribe.

A few months after meeting him, Binyavanga asked me to fly from Geneva to Nairobi for the weekend, to discuss Very Important Publishing Things. I can no longer remember the specific reason for the meeting but, as in all our conversations, I came away believing more in my writing. In our Nairobi summit, in our conversations in Lamu, in our forum, emails and phone calls, we issued a clarion call.

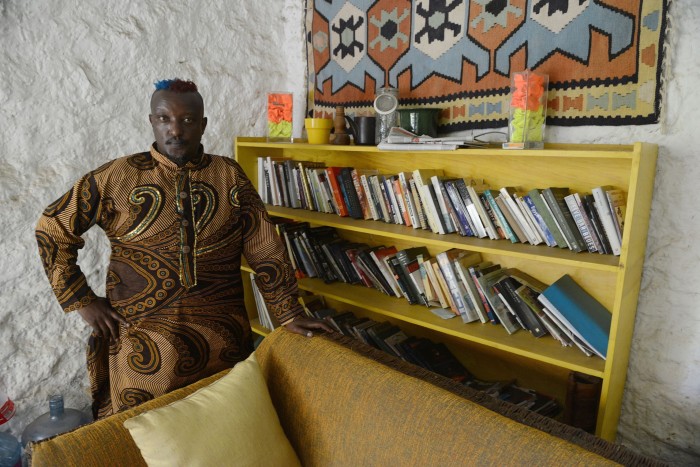

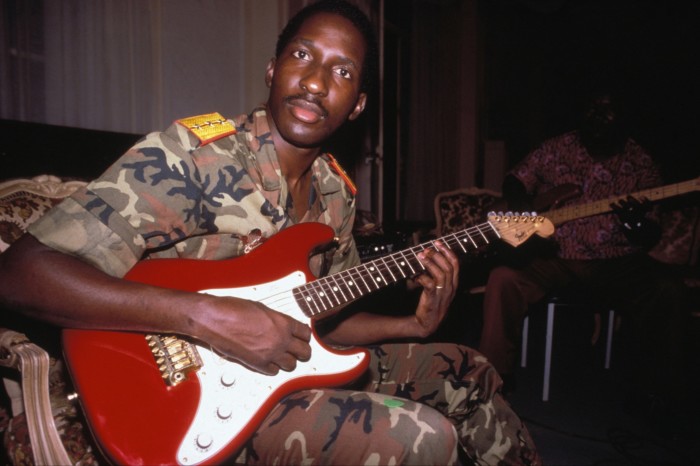

We are young, gifted and African. We vow to decolonise publishing. We are enraged by what we see as outsiders, and especially western outsiders, centring themselves in the story of our continent. Our mission is to change how Africa is viewed. Like Thomas Sankara, the slain leader of Burkina Faso who renamed his people the Burkinabe, meaning upright people, we are daring to invent the future. The Senegalese film-maker Ousmane Sembène once said of his films: “Africa is my audience, the west and the rest are markets.” This is the spirit that drives us.

We want to share our stories with our audiences at home in Africa, but we recognise that power lies in the traditional centres of publishing — New York, London, Frankfurt, Stockholm, Paris. It is a magical meeting of young ambitious people bursting with talent, and ideas. We are touched with fire. Our conversations are loud and liquid. In Lamu, Martin Kimani invents a word, “whiskerish”, to describe our Scotch-fuelled arguments.

We listen as Binyavanga gives an eloquent, impassioned takedown of his bête noire, the Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuściński, linking him to his fellow Polish-born writer Joseph Conrad, whom we are all desperate to decolonise. In the years since Kapuściński’s death, it has become clear that Binyavanga’s instincts were right, that it is dangerous to rely on Kapuściński to give us the truth about any African place or character, and that the manner in which he was lionised in Europe gives us an understanding of how the west views Africa.

From Kapuściński, we flow immediately to VS Naipaul, who presents us with major conflict, as we admire his prose and his clearsightedness but wince at the savage caricatures he makes of our people. I feel rather proud that I am the only one who has read Sir Vidia’s Shadow, Paul Theroux’s incredibly whiny memoir about Naipaul, and entertain the group with some of its excesses.

We spend a week in Lamu passing around a Naipaul essay collection that includes his fine essays on the Michael X killings in Trinidad and on the Crocodiles of Yamoussoukro, but we despair at the disdain he shows to black people. Binyavanga convinces us to read Kojo Laing’s Search Sweet Country. I make the case for the American writer Dave Eggers, whose How We Are Hungry I am carrying everywhere. He has written an incredible story about climbing Kilimanjaro, one of the rare examples of a white writer writing beautifully on an African subject. He is the anti-Hemingway, I argue. Eggers is friends with Chimamanda, I learn. And that brings him closer.

We have a lot in common. We are almost all middle class, some born into it, and others like me achieving it through education. We speak a variety of languages, we read widely, voraciously. These friends are the only people I have ever met who read as I read, first greedily, taking in everything, and then reading it all again, forensically, to see how it’s done, how the rabbit gets into the hat.

We obsess over the Caine Prize for African Writing. Binyavanga and Yvonne have won it, Chimamanda and Parselelo have been shortlisted. Those of us who haven’t won it plot to win it, even as we resent the indignity of wanting something as colonial as a prize for African writers that is judged in London and handed out at the Bodleian. We want all that comes with the Caine — a literary agent, a book deal — but we resent deeply that it comes from London.

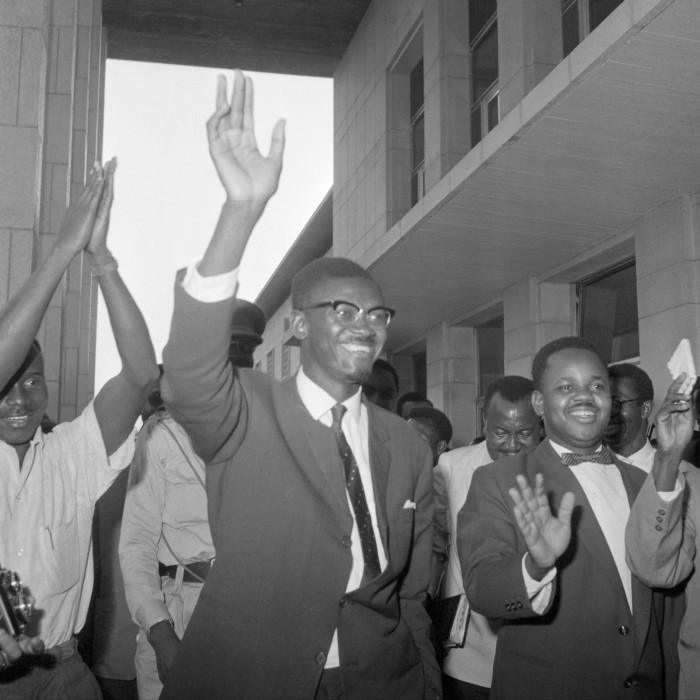

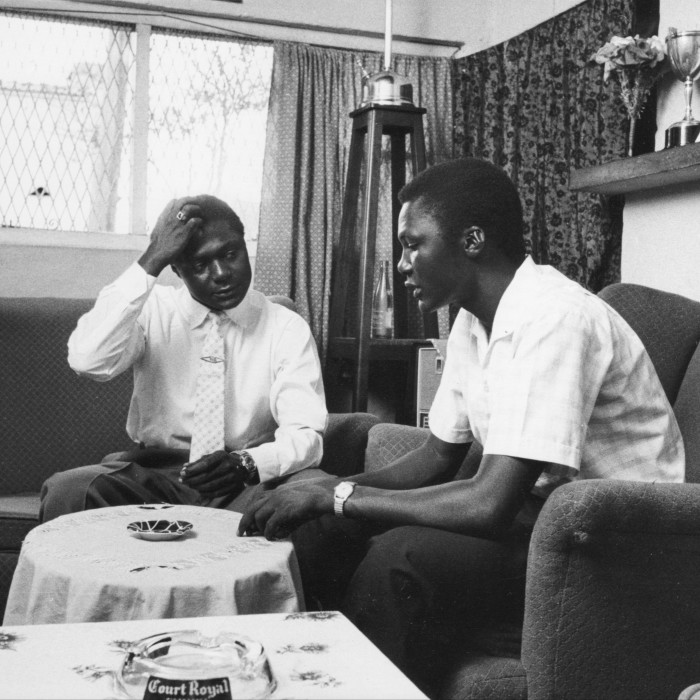

Our politics are pan-African, but not in the sense of the dictators we disagree with. Our heroes are those who died young, whose Africa never came into being: Patrice Lumumba, Thomas Sankara, Tom Mboya. Touched with fire, we are daring to invent the future.

Who gets to decide what is African Writing? We talk about building our own canon, but by participating in a canon built in London and Paris and New York, are we not in fact part of the problem? We mull over whether we should perhaps start our own initiatives, our own publishing companies and literary festivals and build on those.

We read each other’s work and push each other on. Chimamanda has taken on the weighty subject of Biafra. Yvonne is writing a massive book in which the Indian Ocean is a character. Parselelo wants to write a biography of Tom Mboya. Jackie Lebo is obsessed with what makes the successful runners from Kenya stand out. Binyavanga is taking on everything. The synergies are electric.

Binyavanga brings me to tears when he reads a short story of mine, an autobiographical story about the weekend I spent in a mental hospital as a second-year law student at the University of Zimbabwe. “Oh my goodness,” he says, “Oh my goodness. They have no idea, the big people in London and New York, they have no idea what is going to hit them.”

I am crying as he says my story made him cry. He inspires me to send it to the New Yorker, who reject it with a kind, handwritten note of encouragement. I am so excited that I keep the rejection slip on my fridge for years and vow that the next time I send a story, they will accept it. They do, in 2016.

Then he introduces me to the Caine Prize administrator Nick Elam, who invites me to the prize’s workshop at Crater Lake in Naivasha. There I write An Elegy for Easterly, the story that will become the title story of my collection, published in 2009.

But even as I am on my way to being a published author, the bonds of our group are fraying, fracturing, sundering, breaking. The election violence in Kenya at the end of 2007, and in Zimbabwe the following year, force us to confront larger questions, national questions in which there is no simple western bogeyman. And in addition, as in any group where some soar while others are learning to fly, we fall prey to petty jealousies over book deals, we confuse purpose with vainglory, we treat sincere allies with suspicion, we argue over minutiae and wounded egos. We lose something fundamental, the sense of purpose that we had as a group.

Individually, we succeed, each in our own way.

Together, as a group if not a collective, I want to believe that we charted a path for a new kind of African writing. In the footsteps of Binyavanga Wainaina, Chimamanda Adichie, Muthoni Garland, Molara Wood, Teju Cole and many others have come a new generation of writers inspired by our dream. The types of African stories being published in the west have expanded, from historical fiction to romance, from sci-fi to fantasy.

The success of African writers in the west has had a positive impact on publishing and literary production at home in Africa. In the wake of this, an ecosystem of intrepid publishing companies has evolved on the continent, with many successfully negotiating to be the African publishers of works originally published in London or New York.

“Don’t give up your African rights,” was one of the rallying calls in many of our discussions, a recognition that even as we wanted the success that a publisher in London or New York could bring, we were also conscious that it was important to cultivate both a market and an audience on our own continent. “We need to tell our own stories,” Binyavanga often said. Today’s African writers are not only telling these stories but, inspired by his example, are also creating opportunities for others to tell their stories.

I have another recollection, of my time in Kenya in 2007. I attended the festival in Lamu with my son Kushinga, then only four years old. I remember a night when Binyavanga, who was so lovely with children and had made an impression on my son, strode into the lobby of our hotel where we were waiting for him. He was electric and magnificent. Kush jumped from his chair when he saw him.

“He’s here, Mummy,” he said, “He’s really here.”

Binyavanga died much too young, in 2019 at the age of just 48. I miss him. I miss his outsize personality, his capacious generosity, generosity, and his ability to combine savage humour and controlled rage as he did in his essay “How to Write About Africa”. I miss too those early days of frenetic emails, spontaneous meetings and ferocious, whiskerish arguments. I miss the dream that we dreamt when we were young and unafraid, the dream that we would transform an industry.

Petina Gappah’s latest novel is ‘Out of Darkness, Shining Light’

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter

Comments