West Africa’s art scene: uncovering a long legacy of creativity

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

If you visit Igun Street in Benin City, in Edo State, you will come across a street of bronze casters. This guild has passed down the art from father to son for more than a thousand years — the same street where the famous Benin Bronzes were cast is still in operation.

Nigerian arts and culture are thriving. Despite a global economic downturn, an unstable currency, inflation and political turbulence, creative expression flourishes through the power and sophistication of our ancient kingdoms, and our post-independence freedoms.

West Africa has recently come into focus as the Benin Bronzes take centre stage in the restitution discussion. But the truth is: restitution is meaningless if it doesn’t catalyse and connect with the present and the future. The return of objects does not reach its maximum impact if we, as a globalised art world, do not link this moment with the vibrancy of Africa’s contemporary art scene and come together to support its overdue rise and those working within it.

Restitution addresses the injustices of history and is symbolic as it reintroduces missing pieces into our artistic canon. But it is not static. The enthusiasm to return and the self-congratulation that accompanies it should metamorphose into a new connection with the countries from where the works originate. The return of objects such as the Benin Bronzes is not the ending of a relationship; it should be the beginning.

Much of the west African art scene’s success is owed to collectivity and community. Residency programmes founded by some of today’s most successful contemporary artists — such as Kehinde Wiley’s Black Rock Senegal, Yinka Shonibare’s GAS Foundation, Amoako Boafo’s dot.ateliers and the Noldor Residency — encourage homegrown talent and collaborate with exciting galleries on the ground, such as Accra’s ADA and Gallery 1957, Rele, Ko and Tiwani in Lagos, and iterant projects between Lagos and London by Dada Gallery and SABO.

El Anatsui’s Turbine Hall Commission at Tate Modern later this year underlines the impact the Ghanaian artist has made on subsequent generations. Known for his bottle-top installations, his practice goes far beyond that. For Nigeria, we are experiencing a vibrancy in the contemporary domestic scene and in the diaspora — the likes of Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, Nengi Omuku, Victor Ehikhamenor — many of whom feature in Gagosian London’s upcoming show Rites of Passage.

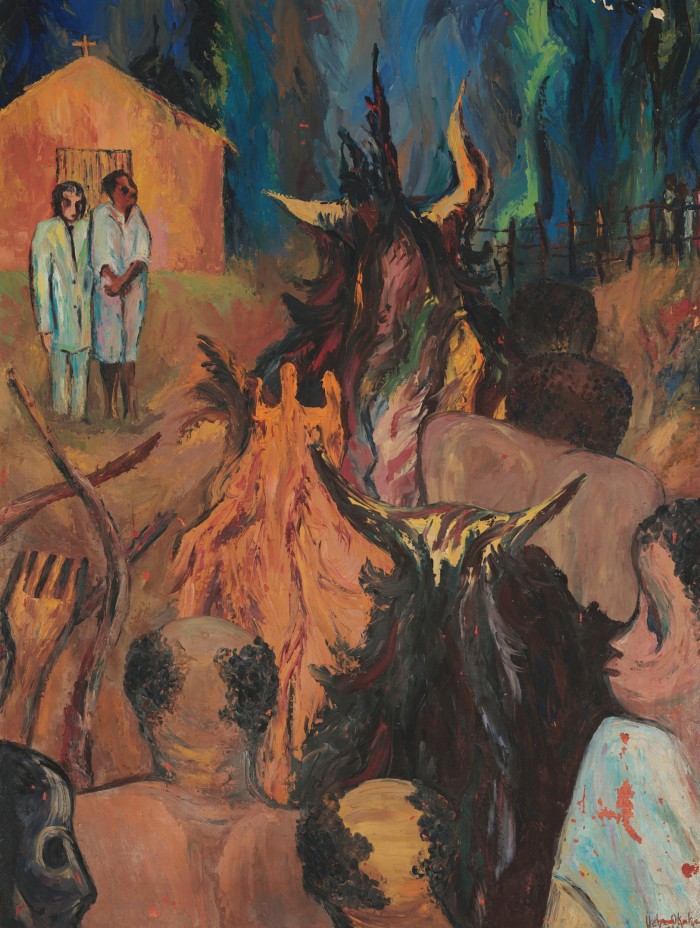

In the 20th century, the political realist works of Aina Onabolu and Akinola Lasekan, the cultural revivalism art of Ben Enwonwu, and the anti-colonial, antinationalist art of Uche Okeke and the Zaria Society were all defined by avant-garde ideologies. As I write in the wake of Nigeria’s elections, I think of Demas Nwoko’s “Nigeria, 1959” (1960). Nwoko sought inspiration from European Symbolists and Post-Impressionists such as Henri Rousseau and Paul Gauguin and, with Uche Okeke’s call for a “natural synthesis” of tradition and western culture, merged the two. In the political disquiet a year before independence from colonial rule, the white officers are long-drawn-out symbols of disillusionment — tired and almost ghostly white — set against the characters behind, where shadow cloaks black faces. The brushwork is elegant and considered, and there is something quite biblical in the composition — an ominous foreboding. This tipping-point image is part of a broader art history of post-colonialism, the discourse of which still ripples through contemporary art today.

The possibilities of west African art are exciting, but it cannot be an island. How can the western art world engage and support institutions in west Africa and across the continent, and connect these thriving hubs with their own so that this creative moment is sustained? In the pursuit of a truly global art ecosystem, one could envision a true and equitable circulation of cultures. If globalisation can bring Africa to the world and the world to Africa, how does this circulation produce returns?

Optimism is at the heart of African sensibility. The late curator Okwui Enwezor said, “The future belongs to Africa because it seems to have happened everywhere else.” In many ways, The Edo Museum of West African Art (EMOWAA) — where I have recently been appointed curator, modern and contemporary — is emblematic of such a bright future. Due to open in stages from 2024, it will be a world-class arts, culture and heritage complex that will celebrate, research and conserve west African and diaspora art from antiquity up to the modern day, as well as heritage and history. Its ambitions and scope extend much further than a repository for Benin Bronzes.

What does a museum for west Africa need to do? How does this differ from its western counterparts? Economic uncertainty means that a relevant African-based museum must do much more. The creative sector is one of the fastest growing, and African cultural institutions such as EMOWAA should provide an ecosystem to nourish skills, exchange and opportunities for creatives and cultural heritage specialists. There is an urgent need for creative hubs with research labs, galleries, education and performance spaces, all of which are embedded in EMOWAA’s plans.

Until the mid-1990s art history didn’t have a field that focused on modern and contemporary African art. We found our own scholars to fill these gaps — historians and curators such as the late Okwui Enwezor and Chika Okeke-Agulu, whose impactful academic careers insist on the importance of the work that African artists, living in and outside of the continent, have made and continue to make. One of my principal goals at EMOWAA is to build on these efforts to tell our stories and extend the intricate connections that already exist.

My first remit: Nigerian Modernism. The civil rights movement of the 1960s, when the sociopolitical circumstances in the US highlighted racial injustice, catalysed unprecedented creativity. Artists such as Faith Ringgold, Jacob Lawrence and Betye Saar in the US were making work about their predicament at the same time as Nigeria’s Modernists such as Uche Okeke and Demas Nwoko were wrangling with a two-fold optimism and criticality in a post-independence Nigeria. Art had to play a role in the transformation of society — in majority-black nations, issues of identity and representation take on new meaning. Following the rallying events of the Black Lives Matter movement, we are presented with an opportunity to foster curiosity, research and support for a vibrant new art scene which is, in fact, just the uncovering of a long legacy of creativity. As we reconfigure how to tell a more expansive story of what it means to be human, we must look to Africa.

To do this authentically, we must engage, support and collaborate. Long-term investment — by way of financial support, institutional partnerships and collaborative initiatives that prioritise culture as a nation-maker — must ensure that the art scene we have fought so hard to build for ourselves is connected to a global story. Supporting the future — museums, artists and curators of the future — is at the core of what is exciting in west Africa. The role of the artist is to bring their view of the world to us, to challenge what we thought we knew or to remove the limiting blinkers of history to see ourselves in new ways.

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter

Comments