China steps in to stem outflow from domestically focused ETFs

Simply sign up to the Exchange traded funds myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

It takes a lot to outdo investment manager Cathie Wood in the value destruction stakes, but Chinese President Xi Jinping has, arguably, overseen this impressive feat.

Wood is renowned for guiding Ark Invest through its meteoric rise as a provider of tech-focused exchanged traded funds — and its subsequent, dramatic fall. As many investors jumped on the Ark rollercoaster shortly before the start of its stomach-churning descent, its range of ETFs destroyed $14.3bn of wealth in the ten years to the end of 2023, according to data provider Morningstar. That is by far the worst out-turn for any US fund group in the period.

As befits today’s superpower rivalry, though, Beijing has responded in kind, in a way. Investors in US-domiciled mutual funds and ETFs lost even more in China-focused funds over the same period: some $14.8bn, Morningstar found. A bear market, powered in large part by Xi’s policies, destroyed wealth at a faster rate than Ark’s mistimed bets on tech.

If you then factor in the losses sustained by China-focused funds domiciled in the rest of the world, Xi emerges as an even clearer “winner” of the gold star for wealth destruction.

In all, it is a sobering wake-up call for the legions of investment banks and asset managers that predicted a great leap forward for mainland Chinese securities when they started being added to global indices, in 2018.

So stark has been the fallout from China’s stock market reversal that it has led to ructions unprecedented in the ETF market globally.

ETFs are designed to trade at a price very close to their underlying net asset value. And they almost always do, thanks to incentives built into their structure that reward arbitrageurs, known as authorised participants, for closing any valuation gaps that do emerge.

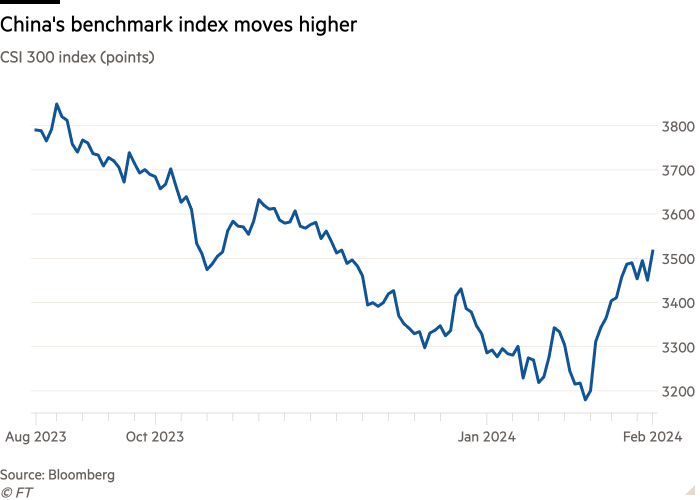

However, this mechanism broke down in China in January. Share prices for some domestically domiciled ETFs investing in US and Japanese equities jumped to premiums of more than 40 per cent to their net asset values, as Chinese investors — seeing the benchmark CSI 300 index plunge 45 per cent from its 2021 highs — scrambled to get their money out of domestically focused investments.

But, because of the investment quotas that Beijing maintains in order to limit capital outflows, the issuers of the ETFs were unable to issue more shares and bring supply and demand back into balance via the arbitrage process. Hence, huge price premiums remained, even though they are simply not meant to exist for ETFs.

“China is going through another stage of worrying about the capital outflow, so they are restricting the amount of money that can go out of China legally,” explains Stewart Aldcroft, an Asian fund management industry consultant at Langley Castle Consulting. “The Japanese market has performed exceptionally well. And, now that the US market, with the Magnificent Seven [tech stocks], has done very well, and they have moved diametrically in the opposite direction to the Chinese market, Chinese investors want more of these and less of the Chinese market.”

The most recent leg of China’s equity sell-off has been driven by worries over weak economic growth amid a housing market slump, as well as fears among foreign investors of mounting US sanctions on Chinese companies, and the risk of a conflict over Taiwan.

But these factors have only augmented underlying fears that Chinese companies on the wrong side of Beijing’s domestic policies could see their share prices plunge — as has happened to education, technology and healthcare stocks.

Foreign investors, at least, have the freedom to vote with their feet. Net inflows into US-listed emerging markets ETFs that expressly exclude China more than tripled, to $5.3bn, last year, as China-focused ETFs saw net outflows of $802mn — compared with $7.5bn of inflows in 2022, according to an FT analysis of ETF.com data.

State intervention can be a double-edged sword, however, and what the Chinese Communist party (CCP) has taken from the markets it is now seeking to put back.

In the first two months of this year, China’s “national team” of state-backed institutions ploughed Rmb410bn ($57bn) into domestic equity ETFs, according to calculations by UBS. Other, heavier-handed, interventions have included a crackdown on the short selling of stocks and the imposition of temporary trading bans for some funds that sold significant tranches of domestic equity.

This wall of buying has helped mainland stock markets recover, sending the CSI 300 index up 11 per cent from its January low, by March.

It has also provided a level of price protection, similar to that offered by a “put” options contract. “Beijing has offered up a ‘Beijing put’ to [mainland] A-share investors,” argues Jason Hsu, chief investment officer of Rayliant, an emerging market-focused asset manager. “State-controlled funds and regulators will defend the current market level. This isn’t buying up the market. This is taking away the downside.”

Hsu regards China’s actions as similar to the Federal Reserve’s efforts to prop up the US market during the 2007-08 global financial crisis.

“Beijing has been studying how the US rescued its economy and restored confidence after the real estate-induced market collapse that destroyed household balance sheets and took down financial institutions and the stock market,” he says. Hsu adds that China has also seen “what not to do” from studying Japan’s 1990 real estate-induced market collapse.

These actions by the CCP are not aimed at the stock market at large, but specifically into its priority sectors.

January saw the launch of the CSI A50, a new blue-chip equity index designed to attract money to sectors deemed strategically important, such as renewables and semiconductor manufacturing. By the end of February, 10 ETFs had been set up to track the new index and raised more than Rmb10bn ($1.4bn), according to China’s Cailian Press.

Even so, not everyone is convinced Beijing will be able to pump the market up indefinitely, without addressing the country’s underlying economic problems.

“Every effort that China has made so far to prop up the market has failed and it has failed for the most fundamental reasons: there are problems in the market itself, not least with the property companies,” says Aldcroft. He believes there is little chance of a meaningful rebound until those underlying problems are resolved.

Comments