‘War on woke’ fails to damage the appeal of sustainable ETFs

Simply sign up to the Exchange traded funds myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

A political “war on woke capitalism” has soured sentiment towards investing according to environmental, social and governance (ESG) principles — delivering a blow to the whole concept of doing well by doing good.

But behavioural scientists reckon that those asset managers predicting that “ESG will be dead in five years” are ignoring fundamental truths about how investors act.

They have found that, while political storms might blow through investment communities, people’s underlying values change very little as a consequence.

“Evidence would suggest about 70 per cent of the investor population is willing to give up something to reflect their desire to do something in the world,” says Greg Davies, head of behavioural science at Oxford Risk, a consultancy, citing research on thousands of individuals over the past decade.

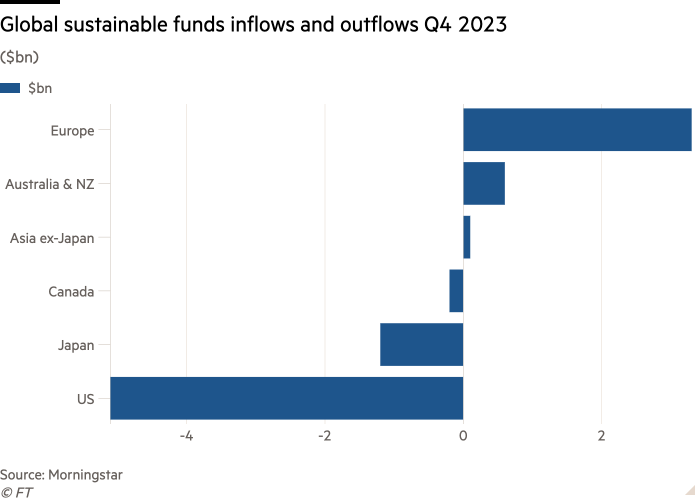

On the surface, however, it can be hard to detect that underlying support for ESG investing. Fund flows into global sustainable funds turned negative in the fourth quarter of 2023 for the first time ever, according to data provider Morningstar.

Investors in the US led the retreat, pulling a record $5bn from US sustainable funds. Managers, listening to the change in the mood music, launched just seven new sustainable funds in the US during the fourth quarter of 2023 — fewer than at any other point in the past three years.

But, in Europe, passively managed sustainable fund strategies, including exchange traded funds, held up well.

Morningstar’s research showed that European sustainable funds proved more popular than those elsewhere and garnered $3.3bn of net new money in the fourth quarter of last year. This was largely thanks to passive funds including ETFs, which collected $21.3bn while their actively managed sustainable counterparts bled close to $18bn.

This apparent demand for passively managed sustainable funds not only runs counter to the broader media narrative that we have reached “peak ESG”, but may also confound some market observers.

However, James Purcell, sustainable finance executive and co-author of Sustainable Investing in Practice, argues that the sustainable investment universe is more complex than often supposed — especially when it comes to use of ETFs.

“Investors with the strongest passion for sustainability are often the most demanding,” he says — and he believes this passion can actually put them off broad-based fund products that might compromise those values.

Purcell reckons there are many reasons why an investor might choose a sustainable ETF — and not all of them are related to sustainability. While some might be seeking to align their investments with their values, others might simply be swayed by ETFs’ performance in prior years, for example.

“Therefore, ETF outflows do not need to imply that value-aligned investors are retreating from their commitment,” he concludes.

Davies warns that the current furore over ESG investing — which centres on companies making exaggerated claims or “greenwashing”, or failing to prioritise returns — is in danger of obscuring investors’ true values.

“The conviction, which I heard often from senior bankers, that investors would not give up returns for impact seems self-evidently nonsense,” he says. “Most individuals willingly give up some wealth to do good through philanthropic donations.”

Nonetheless, both Davies and Purcell acknowledge the problems of greenwashing — a practice many ETFs stand accused of employing.

In Davies’s view, these problems stem from the asset management industry’s misunderstanding of human nature. He thinks the massive relabelling of funds that took place — especially in Europe — to include “sustainable” or “ESG” in their names, was inspired by a mistaken belief that investors would choose them only if “impact could be achieved with no loss of returns”.

This approach led to a muddy solution that was not investing for impact, it was “just investing”, says Davies. As a result, it left those investors who were interested in outcomes, aside from returns, unserved.

Purcell’s view is kinder to the asset management community over its changes to fund names and labels.

“Greenwashing is rightfully a concern,” he says. “However, some greenwashing accusations originate not from a deliberate attempt to mislead, but rather from a different interpretation of sustainability.” He points out that an ETF’s small print might, for example, clearly state that its choice of shareholdings is based on relative ESG performance within its sector. For example, an oil company might be in an index, and held by an ETF, simply because it has better green credentials than another oil company.

“This leads to horizontal hostility between ecosystem stakeholders, and greenwashing accusations often emerge,” Purcell notes.

For Rahul Bhushan, managing director and global head of index at Ark Invest Europe, a lot of the sniping against ESG and sustainable fund providers is due to confusion on labelling. “I think it’s essential to clarify the distinction between ESG investing and sustainable investing,” he says.

But he is adamant that investing sustainability can be good for the bottom line. “The belief that sustainable investing demands a trade-off against returns is, frankly, in our view, inaccurate,” he stresses.

While analysts continue to argue that point, James Lawson, managing partner at Tribe Impact Capital, an impact investing wealth manager, says his experience has taught him to focus on individual aspirations.

“It’s rare that an investor wakes up and asks for ‘some ESG’,” he points out. “Instead, we find they’re more interested in what their investments are doing to harm, protect, or support people and planet.”

Hortense Bioy, global head of sustainability research at Morningstar, agrees that the current debate has not extinguished interest.

“It’s hard to predict investment flows and performance, but recent surveys show continuously high investor interest in sustainable investments,” she says. “We can therefore expect demand for ESG funds to continue, and potentially rise, relative to current levels.”

Comments