Renzo Piano: ‘Buildings are like children – you want them to have a happy life’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“I build flying vessels,” says the Pritzker Prize-winning Italian architect Renzo Piano, recalling some of his most iconic buildings: the Shard in London, the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco and Paris’s beloved Centre Pompidou. All distinct, many groundbreaking, but each linked in his mind by a conceptual thread that ties into the works he is busy finalising as we speak: a mixed retail and business square at the centre of London’s regeneration of Paddington; and a development that is part of Monaco’s €2bn project to extend its coastline 15 acres into the Mediterranean.

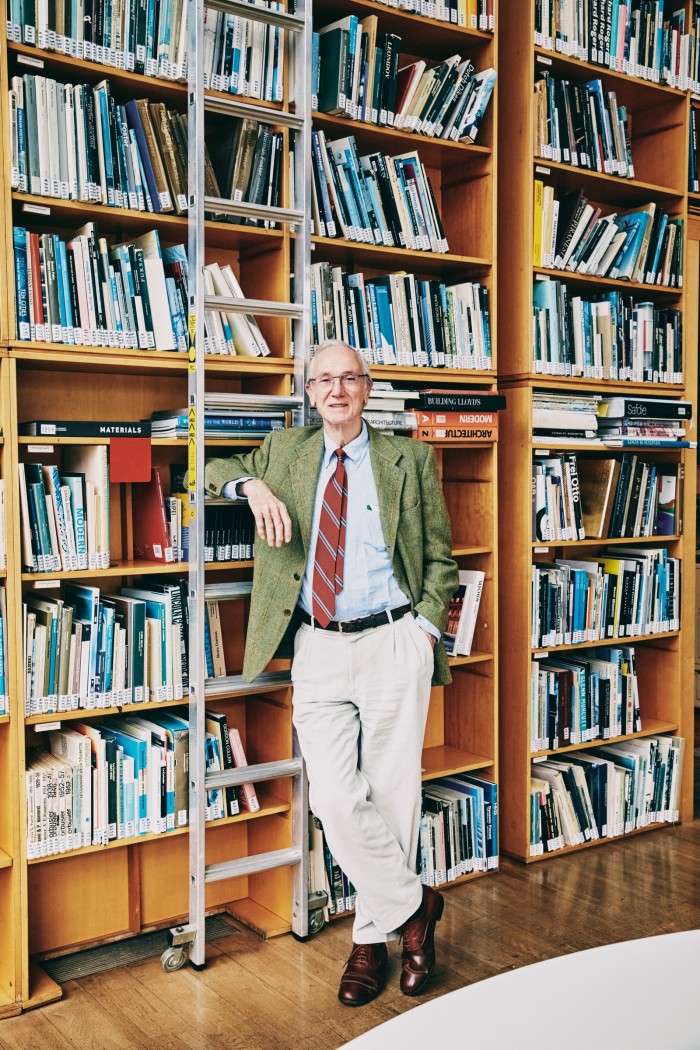

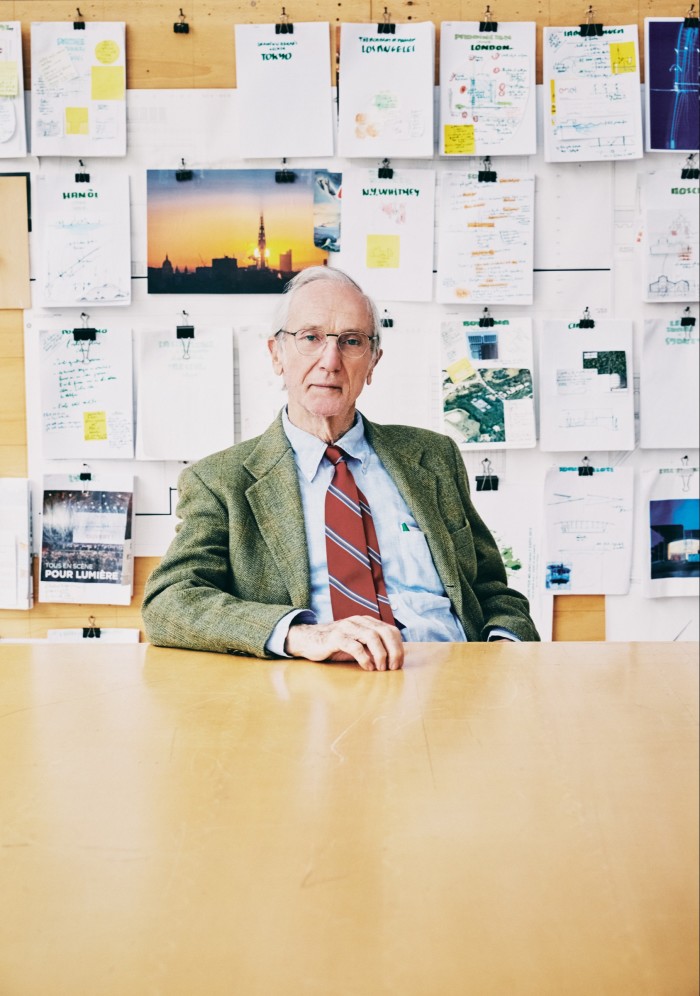

Piano is all smiles under silver-rimmed glasses and a sweep of white hair. The mere mention of one of his buildings sets him off at 100 miles an hour: anecdotes, laughter and memories spill from him in a soft Italian lilt. He is honest, humble and at times dreamily poetic about his work, but at 83 there’s a searing intellect behind those intense blue eyes that remains razor sharp. “All my buildings fly, which when you think about it makes perfect sense because an architect spends his life fighting against the force of gravity,” he says. “By levitating a building, it does not take from the city and its people – it gives something back.”

He is, of course, much more than a conjurer of levitation. His buildings are fantastical feats of engineering and his approach was shaped by his earliest experiences. He was born in 1937 into a family of Genoa builders by the Mediterranean. “I grew up after the war with this unforgettable feeling that making buildings was pure magic, because from around the age of seven I’d go to my father’s building site and sit on the sand to watch them work,” he says. “There would be no shape, just material, but you would return the next morning to find something solid, straight, vertical and well done. When you grow up this way, you don’t worry too much about what you will do in your life – it is pretty clear, it’s in the blood. But also you come to understand that building is a beautiful gesture. It is the opposite of destruction. It is edification and, in many ways, a gesture of peace, especially when you are creating buildings for people because they are civically important.”

Piano knew he wanted to be an architect by the age of 18. “I will never forget the day I went to tell my father. He watched me for a little while, as he was a man of few words, and finally said, ‘Fine, but why would you want to be an architect when you can be a builder?’ The builder was God in my family and, of course, I eventually became an architect with a big passion for construction. They call this technique, but people fail to realise it is not just the making of things – in ancient Greek, the word is also about the process of invention and creation, and that is what it means to me.”

Living by the sea has profoundly shaped Piano’s view of the world. It informs the masterful interplay of light that is so fundamental to his work – as was witnessed by the filmmaker Carlos Saura, who gave him the mantle “The Architect of Light” in a 2018 documentary exploring the relationship between architecture and cinema. “At my age you risk becoming sentimental about these things, but light gets under your skin, especially if you grow up by the Mediterranean. It is not really a sea but a consommé of culture – it’s a soup rich in colour, light, vibration, sound and voices, and if you have ears to listen and eyes to see, it becomes part of your baggage of experience and you carry it with you,” he says. “Light is magic and probably one of the most important materials for architects. It is extremely important when you build a museum, for example – light and lightness, they are very interesting close friends, as is transparency.”

Piano becomes animated when he recalls Genoa. He retains a studio on a verdant hillside in his hometown as part of his practice, Renzo Piano Building Workshop (RPBW), which was established there and in Paris in 1981 (and later expanded to include an outpost in New York). The company employs 150 people and in 2019 ranked third in the Gumari power list of Italian architects, with a 2018 turnover of €13.24m. Piano verges on the confessional when he talks of his coastal home: “I love spending time there, and if I can share a secret, every time I am asked to do a new project, I look first at whether there is water – if there is water, especially salty water, I like it,” he says.

In Monaco, Piano is part of a project that is not only by the water, but on land reclaimed from it. Prince Albert of Monaco’s billion-euro passion project will create Mareterra, a development consisting of residential, cultural and recreational spaces. As it takes shape, the builders have been careful to protect local animal and plant species, and Piano’s design (a series of residences called Le Renzo above a port and retail plaza) will be the crowning glory of the district – the tallest in a row of buildings that rise in scale from east to west.

The focus on sustainability was imperative for Piano, whose work has long been associated with eco-invention. He believes it will drive the future of architecture – in 2020, he completed a carbon-zero hospital in Uganda and three more are under way in Greece. He boasts about the initiatives in Monaco like a proud parent. “It’s a massive plan made by [architect] Denis Valode, and [landscape architect] Michel Desvigne is also on board and is planting 1,100 trees. I think there will be almost 8,000 trees in total and 80 per cent of the buildings will have renewable energy,” says Piano. “The construction of my building is a flying vessel on the seashore of Monte Carlo, and I have designed the promenade from Port Hercule to Larvotto beach.” The district is due to be completed in 2024 and some of the extension’s seafront homes will range from 350sq m to 1,800sq m. The largest are expected to come with lofty price tags, stretching into tens of millions of euros.

“But it’s about the sea. It is always the same – it doesn’t matter if you are in New York [where he conceived the Whitney Museum of American Art], San Francisco [his California Academy of Sciences] or Tokyo [Maison Hermès]. London, of course, has the Thames, where ships sailed long ago,” he says. “Water is magical because it gives back, it doubles everything. When you see a ship, you see the real ship and you see its reflection.” He points to his firm’s design for Istanbul Modern by the Bosphorus. “The roof of the building holds water and it is like a mirror,” he says. “Water is a flirt, it constantly flirts with the light, so there is always something between them.”

But what of his buildings located at the heart of the world’s cities? “Beaubourg is a ship,” Piano laughs, referring affectionately to Centre Pompidou by the name of the district in which it is built. The seminal building – conceived in collaboration with Richard Rogers when Piano was based in London – is credited by some with changing the perception of architecture.

“It was 1971, just three years after the civil unrest of 1968 in Paris,” he says of perhaps his best-known public space. “We were the bad boys coming from London with our Beatles haircuts, and it’s true there was a rebellion against the culture that was building museums – ours was far removed from the marble monument – but it did not change things; it witnessed a change,” he says. “In the life of an architect, if you are lucky enough to be in the right place at the right moment, you can witness change, talk about it, tell a story about it. I was in Berlin when the Wall came down in ’89, so we built a building right where it once stood. The California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco [an eco-groundbreaker with a living roof of plants and wildflowers that opened in 2008] was the first in America without air conditioning, and we recycled practically 98 per cent of the materials.”

In the same way, Piano says the Shard is a building that witnessed the need to intensify life in the city. “It is about connectivity as it flies above London Bridge Station, bringing people together with public transport,” he says drawing synergies between it and his latest development, a centrepiece 18-floor building and square with retail, dining and leisure at the heart of Paddington’s regeneration project (set to complete in 2022). “It will bring intensity to the area with people coming to work, to meet and to stay together. It is also about stratification because cities are most beautiful when they witness different moments – there are visible layers of different ages and so this is part of that story,” he explains. “This building is a crystal. It’s very light and its design is about luminosity from both inside and outside. Also, the building levitates – it tries to fly because we wanted the ground floor to be a continuation of the city. It is different from the Shard but not in terms of logic. We don’t have car parking because cities must accept we can’t have cars, they must accept public transportation – that is the future, it is a small revolution.”

A quick scan of Piano’s office reveals how these projects consume his waking hours. Piles of drawings, equations and photographs are pinned to the walls. Models and blueprints rest beside rows of sharpened pencils on tables. Scribbles of thoughts and ideas are dotted everywhere on fluorescent Post-its, and in one corner sits a tape dispenser, which Piano has claimed as his own by writing “Renzo” on it with a black felt-tip pen. They tell of the narrative behind each building – but relating a story is not enough for the architect.

“You need another dimension. Take a good movie – I love the filmmaking profession – but even when you have a good story, if you don’t include suspension or a lightness in the language, it does not work,” he says. “Architecture is also about illusion. It points to something but you don’t really need to know what. This is also true in music or a book, you don’t put everything in, you leave space for the imagination. You need that because changes must be celebrated with expression and must be built – with something that touches human beings.”

Piano views all his buildings as offspring. He refuses to choose a favourite. “I touch on this in Atlantis, a book I did with my son Carlo, where we take a metaphorical journey in search of Atlantis, because these buildings represent a constant search for beauty that is always just out of reach,” he says of his work. “I mean beauty in the ancient Greek sense of kalos, something good and noble. But buildings are like children – you are very keen for them to be happy. Some have a happy life and others don’t, and then you suffer. Thank God most of my buildings have had a happy life – sometimes it’s an intense life, but a civil life is a good one because you are making places for people. And the first thing you need to be really happy is to be loved – to be adopted, even if that takes time to achieve.”

Comments