‘Fire hose’ of health innovation risks going down the drain

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Technologists around the world are developing digital tools to help distribute a hoped-for Covid-19 vaccine, while innovators are devising ingenious data platforms to help us better respond to the next pandemic. Unfortunately, much of that work may be wasted.

As a digital health adviser to global health organisations, I have seen countless dazzling ideas since the pandemic broke out. These include electronic sanitising wands, AI-driven mental health platforms and online dashboards that allow medical researchers to track outbreaks.

Yet I often leave pitch sessions more worried than encouraged because we lack adequate means for scaling the best of these tools to reach millions of people rather than just thousands. We also devote little effort to serving people who will need these innovations the most — the elderly and those on low incomes.

The Covid-19 pandemic has exposed deep challenges within our nascent digital health sector. For one, we are drinking from a fire hose of innovation, with many governments and health systems overwhelmed by the sheer volume of tools and ideas.

Worse, there is little consistency in privacy standards, interoperability or regulation. The end result is a cacophony of good intentions and meaningful contributions from tech companies, governments, academics and non-governmental organisations that threatens to drown out the best ideas in a din of inefficiency.

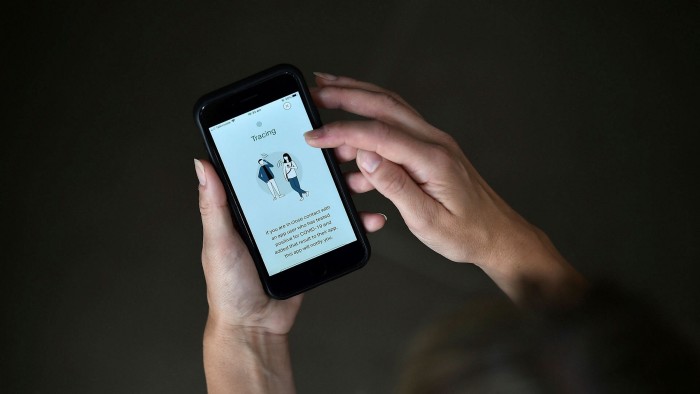

We now have redundant testing and tracing tools, a lack of co-ordination between health databases, sham products being pushed into the market and online platforms used to spread misinformation.

Political fights over ownership of data have further complicated the picture, while there are broader questions about bias in AI and the proper role for commercial players in global health.

For instance, a non-profit group called the Commons Project is developing a secure means to document and verify who has received a Covid-19 vaccine, which governments will probably require to bring global trade and travel back to pre-pandemic levels. Meanwhile, private companies are looking to provide related technologies for vaccines and diagnostics for outbreaks.

Those innovations warrant support, but they also raise challenges. Will the information be protected or shareable, and by whom? How would these tools work with existing health records and data sets? Who would pay for and have access to them? Who would handle oversight?

We need a coherent global framework to shape and implement these approaches so that innovators, health authorities, investors and citizens can all benefit. We already have models including Gavi, the UN-backed global vaccine alliance, and Cepi, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations. Now we must develop an infrastructure to support policies around digital public goods — whether as part of an existing institution or something new.

Send us your ideas on how technology can improve healthcare

The FT/Lancet Governing Health Futures 2030 Commission comprises independent leading experts who will publish their peer-reviewed report in late 2021. Share your views here.

Read the rest of our Future of AI & Healthcare special report here.

To be better prepared for the next pandemic, governments, multilateral organisations and leaders from the private and social sectors must address five areas of weakness:

First, put sharper teeth in the UN’s Digital Roadmap to enable digital innovation as a global public good while protecting the interests of innovators.

Second, clarify the rules for consistency around privacy, interoperability, data governance and ethics.

Third, design a way to make suitable tools accessible to those in vulnerable communities often left behind in health innovation.

Fourth, develop initiatives, technical assistance and incentives to help scale innovations with the broadest utility, rather than cool ideas aimed at the few.

Fifth, ensure substantial and sustainable financing, with clear value propositions, multi-sector investment schemes and metrics for success.

I was recently part of a World Economic Forum panel, judging proposals for digitally-driven social enterprises to respond better and rebound from health crises. Many submissions were impressive: InteleHealth from India, for instance, seeks to bring high-quality telemedicine to remote populations by connecting health providers with front-line doctors; HelloBetter from Germany addressed depression, anxiety, insomnia and burnout by virtually connecting users to licensed therapists and a moderated online community.

But all the ideas in the world will not help without some collective means for evaluating, regulating, disseminating and funding them. We need to build these measures before the next pandemic. As the Ebola crisis showed, it is impossible to deploy innovation at scale when you are in the midst of disaster.

Covid-19 has focused our collective attention like nothing since the second world war. Our response then — the creation of the UN — provided an important framework for international co-operation. Nearly a century later, we need a new arena focused on digital diplomacy. The stakes have never been higher. To meet them we must be as innovative on policy as we are with products.

Steve Davis is a lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Business and author of ‘Undercurrents: Channeling Outrage to Spark Practical Activism’

Comments