Rwanda venture tests digital health potential in developing world

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Babylon, a UK-based digital health group, began operations in Rwanda in 2016, there was already strong interest in the use of artificial intelligence to improve the country’s medical system.

Babylon’s telemedicine service has since registered 2m users across the African nation and handles 3,500 daily consultations. But its progress highlights the constraints and debates around new technology even as multiple providers expand the use of digital healthcare around the world.

While digital tools can potentially support more people affordably and efficiently in stretched healthcare systems, critics have raised concerns about unequal access and say that claims about digital tools such as AI can be overhyped and unproven.

Millions of patients in industrialised nations already use online medical services and apps, and companies are looking further afield for growth. Babylon is scaling up its operations in Africa, Asia and Latin America, while rival Ada Health, headquartered in Germany, is expanding in Tanzania.

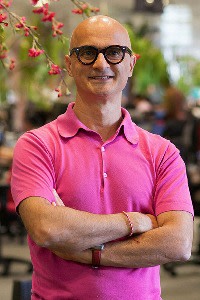

“These countries have an opportunity to leapfrog and not make the same mistakes of our [health] systems created over a couple of centuries,” says Ali Parsa, Babylon’s founder, referring to the ability to target prevention rather than costly treatments. “They can focus on keeping their people healthy, rather than investing in sickness.”

From his UK base, where Babylon has contracted with the NHS, Mr Parsa agreed to launch in Rwanda — rebranding under the name of “Babyl” — after meeting with Paul Kagame, the country’s president. That led to a 10-year contract with the government and the local health insurance system. “It had a small population [12.5m] and an executive that works,” he says. “We were picking up something we could handle.”

At the start of 2018, Babyl announced “the first ever fully digital healthcare service in east Africa using artificial intelligence”. The service would include a chatbot “to take the power of a doctor’s brain and put it on a mobile phone for medical advice and triage”.

In reality, the system remains a more rudimentary form of telemedicine, with plans to test AI over the coming months.

The effectiveness of Babylon’s system in the UK has received mixed reviews. A recent study by researchers at Pennsylvania State University concluded that online symptom checkers “lack the functions to support the whole diagnostic process of an offline medical visit”, with often limited scope and focus on particular diseases.

Academics at the University of Sheffield in the UK wrote in a review of digital symptom checkers globally that they are used primarily by younger, more educated people and there is little evidence of how far medical advice is taken up.

Shivon Byamukama, Babyl’s chief executive, says few people in Rwanda own smartphones (the service is also designed for basic mobile phones, using text messages and voice calls). Instead of using bots to diagnose symptoms, most people text a request for telephone appointments. Nurses call back and transfer them to doctors for consultations. When necessary, patients receive a code for follow-up prescriptions or laboratory tests.

“We take out people from the system that digital health can handle,” says Ms Byamukama. The benefits include swifter and easier access to doctors, even in remote areas, reduced time waiting in clinics and greater privacy.

An evaluation of Babyl in 2018 by Dalberg, a consultancy, concluded it had scope to cut costs, including through the development of more efficient electronic health records. For now, says Ms Byamukama, the company faces extra costs as it seeks to gain economies of scale from its global systems, including a requirement to store all its data on a local cloud server hosted in Rwanda.

Dalberg warned of a “slightly increased risk of fraud through false impersonation” by callers using Babyl, compared with face-to-face consultations. It also highlighted the need to adjust symptom-checking algorithms to “local health and disease patterns and to language and communication practices”.

Send us your ideas on how technology can improve healthcare

The Lancet and FT Commission comprises independent leading experts who will publish their peer-reviewed report in late 2021. Share your views here.

Read the rest of our Future of AI & Healthcare special report here.

Hila Azadzoy, global health initiatives lead for Babyl’s competitor Ada, says use of local health information and languages is critical for algorithm accuracy. “Local epidemiology is core. You need region-specific incidence and prevalence for an optimised disease model,” she says.

Babylon’s Mr Parsa, who says Babyl did not initially compile such Rwanda-specific data for its system, cautions: “People are hyping AI often because they want to get finance. The reality is we are in day one. It’s really in early infancy. AI will utterly outperform our wildest imaginations in years to come and utterly disappoint us in the short term.”

Much of the analysis in the field is funded by the companies themselves and not published in peer-reviewed journals. It is limited in scope, with tight restrictions on the medical conditions examined, and often provides no comparison with rival products or the final outcomes for patients.

Hamish Fraser, a researcher at Brown University’s Center for Biomedical Informatics in the US, recently co-authored an assessment, backed by Ada, of different symptom checkers. He says there is a need for more systematic independent evaluations and clearer requirements by medical regulators for data.

“It’s a bit crazy no one has funded a large-scale study,” he says. “I find this hard to square with the number of patients using digital tools. If you have too high sensitivity, you could overwhelm the health service. A good system could make a big difference, but a poor system leaves people very vulnerable, without a safety net and not getting access until it’s too late.”

Comments