Maxime Flatry will make you fall for art deco

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

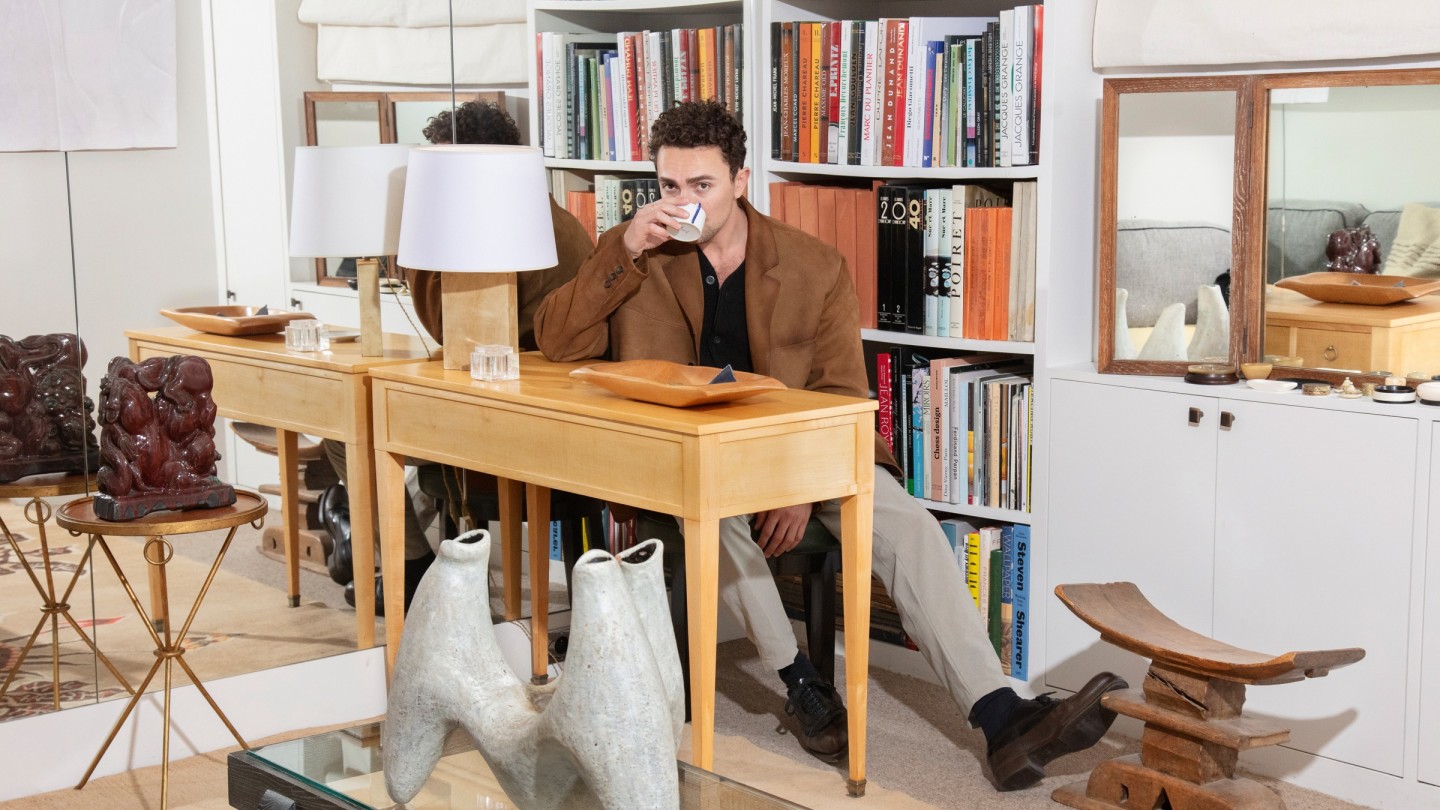

Maxime Flatry is in constant motion. As he welcomes me into his decorative arts gallery on Rue Guénégaud, in the heart of Paris’s Saint-Germain-des-Prés gallery quarter, he immediately starts telling the stories of the tranche of art deco pieces on display: a cubic bergère by Atelier Martine that once belonged to fashion designer Paul Poiret, or a creamy Pierre Chareau armchair whose curves he emphasises with his hands. He may only be 30 years old, and have opened his space less than two years ago, but he is already causing a significant buzz, garnering the attention of private collectors, interior designers and prestigious institutions alike.

“Maxime has rejuvenated the Parisian antiquarian scene,” says interior architect Pierre Yovanovitch. “He is not afraid to take risks and break down doors. His curiosity and understanding of the niche complexities of art deco… shows a genuine eye and real taste.” Last March, Flatry’s eponymous gallery was selected to feature at the exclusive design fair TEFAF; not one to underwhelm, he showcased Yves Saint Laurent’s desk and chair, designed by Elizabeth Eyre de Lanux, c1932, both in stained black brushed oak and white ceruse. They were swiftly acquired by an important European private collection.

Flatry’s journey to this point has been circuitous. Growing up in Sète, a small town near Montpellier, “I spent all my spare time sketching cars,” he confesses. He then moved to Paris to study fashion at the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne. It was during research for his graduate collection that he began to develop an interest in the decorative arts of the 1930s, particularly the lacquer work of artist Jean Dunand, the “system furniture” of Pierre Chareau, and the marquetry of Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann. “It was a real crush, and my first connection with design,” he says.

After college, while designing jewellery for Paco Rabanne and Lemaire (“I think it was my way of getting one step closer to furniture, the jewel being a quasi-architectural piece”), he began to start “my little collection” – jewel-like objects including early-20th-century vanity sets and small objects in mother-of-pearl and ebony “representing those trades that died out after the art deco period”. In 2020 he began selling pieces, often through Instagram.

A keystone item was an ivory bonbonnière (sweet box) with a snail‑shaped cover, which was unsigned but suspected to be by André Groult. “I managed to get in touch with his granddaughter, Lison de Caunes,” says Flatry. “She was deeply moved when I showed her the box, and helped me authenticate and license it. I sold it to a gallery on Rue de Seine. That’s how it all really started.”

“When I felt his love for the work of my grandfather and his immense knowledge of the man he was, I immediately felt a connection to him,” says de Caunes. “It delights me to see how passionate he is about art deco, especially the work of my grandfather, which he continues to bring to life.” Since then, Flatry’s design language has zoned in on pieces by other top names of the period: Jean-Michel Frank, Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, Armand-Albert Rateau and Pierre Chareau. Translation nuances notwithstanding, he says he prefers the term “I defend them” to “I represent them”. And, like the Groult bonbonnière, finding each piece is “a treasure hunt”.

“It was bold for Maxime to embark on this adventure without coming from the design field,” says Olivier Gabet, director of the Louvre’s art department and former director of the Museum of Decorative Arts. “To delve into art deco and defend important names such as Groult, Ruhlmann or Frank, while being hyper-selective, especially in an era obsessed with quantity, is no small feat.”

Following a show he curated at Galerie Chenel – where his art deco pieces were displayed in dialogue with Adrien, Gladys and Ollivier Chenel’s antique sculptures, and which attracted the Parisian tastemakers – in June 2022 Flatry opened his three-storey, 160sq m space at 33 Rue Guénégaud, designed by architect Simon Basquin.

Notable clients began flocking: not just Yovanovitch, but Jacques Grange, François-Joseph Graf and Vincent Van Duysen, as well as fashion figures including Pieter Mulier and Marc Jacobs. “We connected through Instagram in early 2021,” says Jacobs. “It wasn’t until recently that I finally visited his gallery, and it was a delight. Maxime has an exceptional eye and impeccable taste; and in the span of two years has managed to earn the trust, respect and appreciation of collectors. What sets him and his gallery apart is his energy and passion, coupled with a rigorous approach.”

Exhibitions are as much storytelling, or theatrical stagings, as furniture shows. Madame saw Flatry turn the gallery into a quasi-boudoir, evoking the feminine aspects of art deco with pieces by Jean-Michel Frank, Marc du Plantier and Katsu Hamanaka. Perspectives: mobilier – sculpture, in concert with modern art gallery Dina Vierny, saw art deco pieces sit alongside museum works by French sculptor Aristide Maillol, as if connected by an invisible thread.

“The idea is to create a sort of tension between the pieces – a setting where each can be presented as an individual object, and at the same time blend into an atmosphere, a whole, a mise en scène,” says Flatry. For his latest exhibition, From Paul to Paul, Flatry blurred the boundaries with contemporary art by initiating a conversation between the works of art deco furniture designer and architect Paul Dupré‑Lafon and LA-based artist Paul McCarthy. “I found it incredibly clever and exciting,” says Jacobs. “Despite the apparent dissimilarity between these two artists, a profound connection emerged. For Maxime to execute this with such audacity was remarkable, and not a lot of galleries have done such bold things.”

Through his presentation and reframing of art deco pieces, “Maxime has almost made the tastes of the time evolve”, adds Pieter Mulier, creative director of Maison Alaïa, and a friend of the gallerist. “What Maxime offers is very particular and unique to him. Very niche, in the noble sense of the term. And that is the essence of luxury. What seduces me about him is his very snobbish side,” laughs Mulier. “The word often has a pejorative connotation, whereas in Maxime’s case, it translates into exacting standards, and an almost obsessive commitment to rare and precious objects.”

By seeking out exceptional pieces with love, overseeing their restoration with an almost forensic attention to detail, and creating ensembles that involve impressive staging, Maxime Flatry’s gallery has become a place where one comes not just to delve into the significant history and visual opulence of art deco, but to dream.

Comments