1-54’s Touria El Glaoui: ‘Africa is becoming more visible in the art world’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It is an emotional time for Touria El Glaoui. On May 3 the founding director of 1-54, the contemporary African art fair, will be in New York for the opening of its fifth season.

Earlier this month a retrospective of paintings by her late father, the figurative artist Hassan El Glaoui, opened in his home city of Rabat, Morocco.

“There has been a bit of crying here and there,” she says. “Having to put it together without the usual support, talking about my dad not as a father but as an artist was the most emotional moment for me because I had to I try to see it as a way of staying connected with his life. I chose 80 pictures, some only seen before by close friends and family, which reflect the 50 years of living in the city. Yes, bittersweet.”

She has found herself poised between the personal and the professional — organising the exhibition of a man who was arguably the best-known Moroccan artist of his generation while at the same time corralling the 24 galleries and more than 65 artists who will participate in this year’s fair, which opens on Friday.

To reflect her ambition and the growing global interest in African art, 1-54, which is also held in London and Marrakesh, is moving from Brooklyn to New York’s West Village, the heart of the contemporary art scene. Instead of Pioneer Works, a non-profit cultural centre based in a cavernous disused 19th-century factory in the Red Hook district, El Glaoui has opted for an altogether more “happening” venue, Industria, an old garage which modestly claims to have “revolutionised the photo and event industry as the first complex of its kind in the city”.

“It was a difficult decision to move into the city because we worked well with Pioneer Works,” says El Glaoui. “We evolved together and they loved what we were doing.”

But art is business, as El Glaoui recognises as well as anyone. Despite growing up in Rabat with the “smell of paint drifting from my father’s studio”, she admits to being “not even remotely talented artistically”, but she did have a yen for commerce and worked as a wealth management consultant after she completed her education in New York.

“Africa is becoming more visible in the art world and that means the galleries needed a bigger space,” she says. “We had to be in the centre and nearer to Frieze New York. Our new location is amazingly well placed, with the Whitney Museum nearby and the Chelsea galleries within walking distance.

“The problem with Pioneer Works was that there was no access by subway and it was hard to explain to the galleries where Red Hook actually was. I lived in Manhattan and know that New Yorkers do not like to cross bridges. We had to listen to the pain points of the galleries. If we had not moved, there was a danger we might have lost some of them.

“New York is so happening that you have to be there physically to create a network of galleries and collectors, which is why we have managed to attract more US galleries this year. I reckon if we can touch just 1 per cent of the American base we will be in such a better place in terms of private collectors and museums, universities and the institutions relevant to us.”

The line-up of galleries reflects the reality of competing in the global market. The title 1-54 reflects the one continent and its 54 countries, and while it would be too much to expect representatives from all or even half the countries, more artists than before are from the US and the Caribbean. Out of the total 24 galleries showing this year, five are from New York, four from London, three from Paris and one an outlier from Istanbul. Only eight countries and nine galleries are based on the African continent.

From New York, high-profile galleries such as such as James Cohan and Yossi Milo, which are based in Chelsea, and the Danziger Gallery are at the fair along with David De Buck, which is showing four artists: Rashaad Newsome, Tajh Rust and Devan Simoyama, who are all born in the USA, and Marielle Plaisir, who was born in France but works in Miami.

El Glaoui, who speaks with a rapid-fire eloquence, says: “I felt a strong love for African American artists going on when I was at the Armory and Miami Basel earlier this year and we had a lot of African American collectors coming to the fair in New York last year. That was very strange because I don’t think other art fairs have this group of collectors who are really interested in buying art from the African continent.

“The artists we are showcasing are part of a diaspora — some of them a loose mix of African American artists who claim a heritage to Africa.

“It is our mission to show them, though I know there is quite a wide interpretation as to who is part of that diaspora. Do you talk about it by origin or generation or the fact that they all came from Africa originally? We have to let them come to us with their vision.”

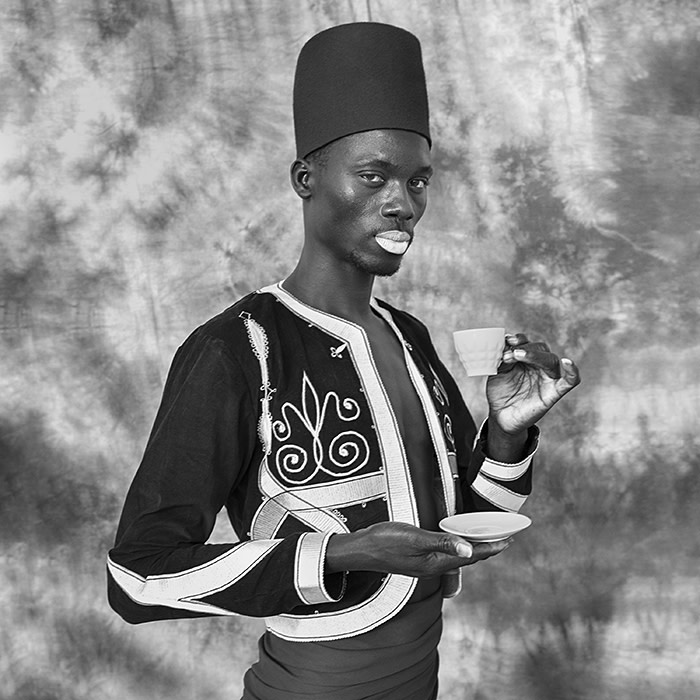

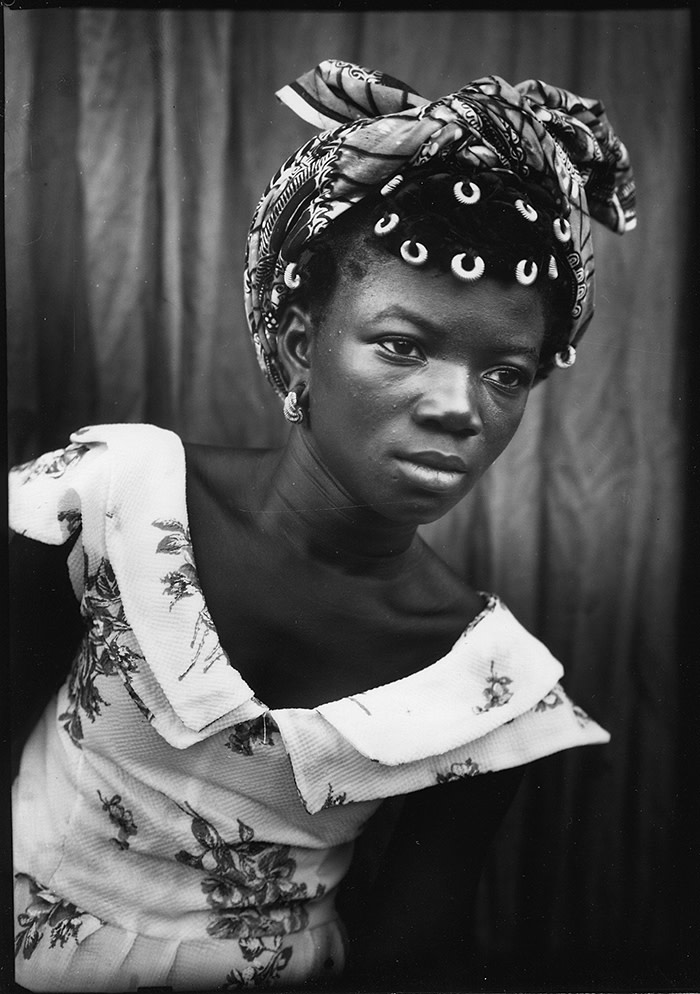

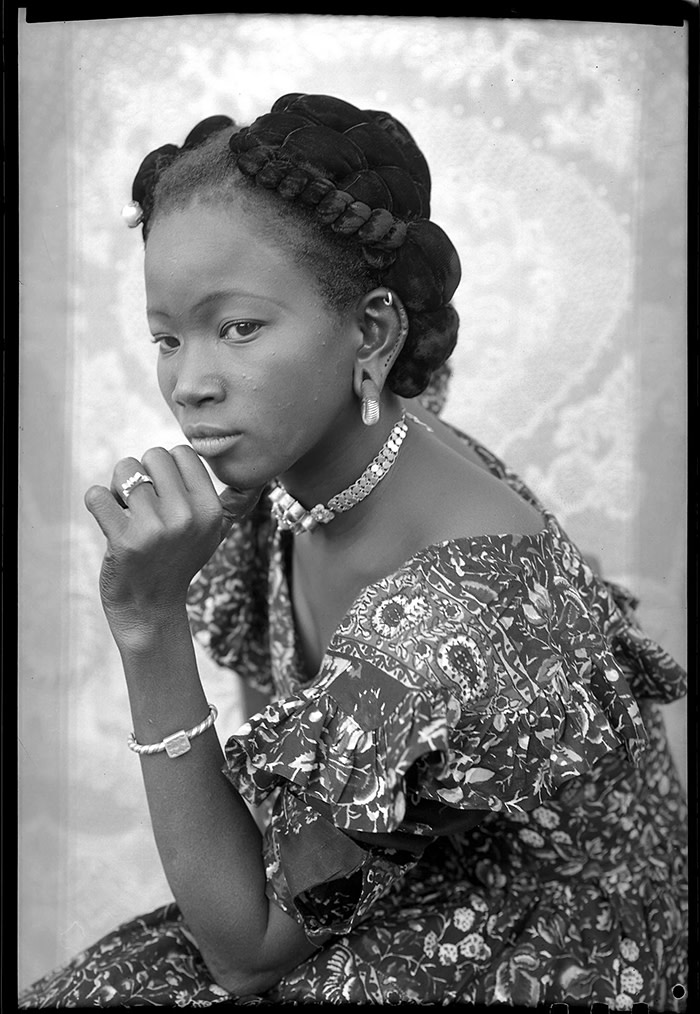

This eclectic mix is reflected in the solo shows, which include the atmospheric black-and-white works by the late Malian photographer Seydou Keïta (Danziger), the trash-techno collages of Elias Sime from Ethiopia (James Cohan) and the bold strokes of Ernesto Shikhani (Perve Gallery, Lisbon) from Mozambique. Really pushing the definition of diaspora is Frenchman Raphaël Barontini, represented by The Pill (Istanbul, Turkey), who is inspired by a Haitian ancestry to explore post-colonialism with an intriguing mix of masks and cubist abstractions.

El Glaoui cheerfully admits that when it comes to style and themes, the artists from the African continent, let alone the diaspora, have “nothing in common” and admits they may lose some of the national identity by being categorised as “African”. It’s a point made by another of the solo artists, Richard Mudariki (Barnard, Cape Town, South Africa) with his distinctive “Africa is not a Country”. It channels Alfredo Jaar’s “A Logo for America”, a neon outline of the United States with the slogan “This is not America”, and questions lazy assumptions about identity and national characteristics.

What the artists and their galleries do have in common is an increasing awareness of the need to share resources if they are to enhance their development. As El Glaoui emphasises, it is easy to overlook the limitations of travel and the cost of getting works of art from, say, Addis Ababa to New York.

“Some galleries are prepared to share a space and the cost of setting up. In the last five or six years galleries like Gallery 1957 in Accra, Ghana, have shown Tunisian artists, while in Morocco, Loft Art Gallery has introduced artists from, for example, South Africa to Morocco.

“I love the exchange from the south to the north, rather than turning to the west all the time.” The enthusiasm for African art is reflected in the global market — up to a point. Earlier this month Sotheby’s fourth auction of modern and contemporary African art in London saw a modest rise in sales of £42,000 to £2,316,625. The star turn was Chéri Samba, one of whose versions of “J’Aime La Couleur” sold for £93,750, well above the estimate. He will be showing at 1-54 along with other artists who sold moderately well at Sotheby’s such as Ernesto Shikhani, Seydou Keïta and Dominique Zinkpè — though the biggest sale was chalked up by Hassan El Glaoui, who is not featured at the fair, with “La Sortie du Roi”, which sold for £137,500.

The hard truth is that the continent still accounts for a fraction of the global art market. According to figures from Africa Art Basel and UBS Bank in 2018, Africa, even combined with South America, made up less than 4 per cent of global sales, which amounted to $63.7bn.

There was some cheer for El Glaoui in January of this year at the Talking Galleries symposium in Barcelona, with the assessment that the African market had shown a dramatic growth from about $21m in 2016 to between $35m and $40m in each of the following two years.

But as El Glaoui remarks wryly: “We were told by an expert that the African market was worth less than Romania. But we have become more visible in the past six years. We have to keep trying.”

May 3-5, 1-54.com

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments