American film-maker Leslie Thornton on the exchange between science and art

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“It’s almost magical because it’s so detached from our day-to-day existence and a bit in the realm of science fiction, really,” Leslie Thornton says of her residency at Cern in early 2018.

The American film-maker and artist was searching for a more approachable perspective on a research centre otherwise sealed off from the public imagination. “I want to say something about the other side,” she explains, “traces of how things work that you don’t usually see.”

Her insights are emerging in a body of work that engages with a history of science, de-emphasising official accounts in favour of everyday “anecdotal histories” moulded from individual memory. The latest, “Flutter” (2019), will be presented as a solo installation by Unit 17 at Frieze New York.

Thornton and I speak over Skype just as she is starting a residency at Caltech’s new visual culture programme. She looks every bit the humanities lecturer, with glasses and thick, fringed hair; she speaks with an enthusiasm tinged with intrigue about the private institute’s “well-endowed and exquisite campus”. For her the role is an exchange rather than an intersection between science and art. “I don’t feel I’m a part of that because I’m not in any way a scientist. I did grow up around scientists so it’s familiar but it’s not what I know.”

Thornton, who is 68, grew up in Evendale, Ohio, where her father Gunnar Thornton developed nuclear-powered aircraft for General Electric’s Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion programme (ANP) before it was cancelled in 1961. A nuclear physicist, he had previously been involved in the Manhattan Project with her grandfather.

Thornton addresses this history in “Cut from Liquid to Snake” (2018), which is screening at Malmö Konsthall until May 26. The film features an eyewitness account of Hiroshima soon after footage of Thornton’s aunt recalling how her father and brother discovered that both were secretly involved in the same “terrible project”.

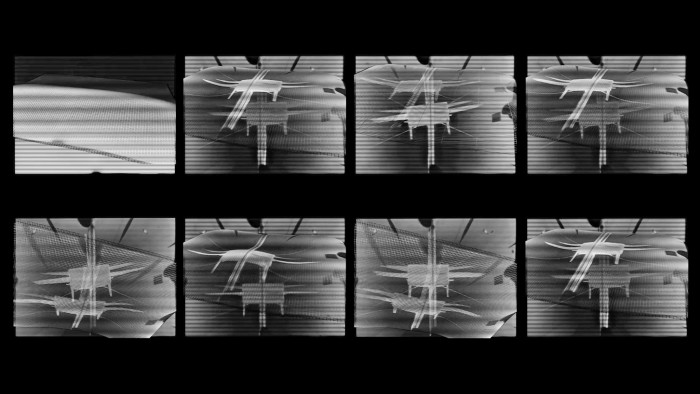

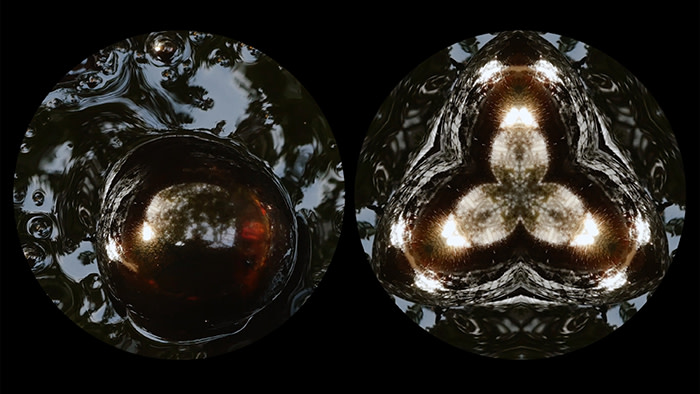

It is strikingly direct for an artist more inclined to the “precarious referencing” used in “Flutter”, which will be played concurrently across two monitors, forming an out-of-synch video diptych. A central motif is the wind tunnel, a structure that tests aeronautics by simulating wind speeds. Thornton recently stumbled on Nasa’s images of the ANP being tested at Langley Research Centre in Virginia, triggering an “eruption of memory” and an astonishment that “the plane looked cute”.

The “flutter” test determines a plane’s ideal wingspan, and Thornton pairs archival videos of winged boxes, which alternately rock or flit erratically, with the agitated buzz of a fly. “A lot of the register of my work and the meaning that you can pull from it occurs in the sound. That’s the subterfuge area,” she explains. The effect here is abstractedly animalistic.

At other points the slow amble of reptiles is spliced with footage of an unsuccessful wind tunnel test. This initially appears to be a higher-stakes outer space mission, imbuing the matter-of-fact voiceover announcement that it is “not working at all” with a chilling sense of misplaced apprehension.

No longer interested in the theatrics of “linear storytelling”, Thornton is adapting to what she calls the “ambient environment” of the gallery or fair, a context in which people come and go freely. She designs her films to be looped, with each repetition adding new layers of meaning.

As references to the atomic bomb merge with those to the cold war or the contemporary age, “demarcations of time start to blur, and once you go through it a second time it all becomes part of the present. All history is structuring our present, all of it feeds into our present.”

For Thornton, the current moment is one of “de-evolution”, in which traditional frameworks are collapsing in part due to the political climate, the internet and invasive security measures. Her tone on these matters is forthright, but she is prone to punctuating her more provocative statements with a deadpan laugh.

Asked if it is the human condition to live in fear of self-annihilation, a threat felt as deeply by many people now as during the cold war, she concedes that “it may be the beginning of something awful but there is just no way that it can all turn to darkness”.

Her focus on science, which she rarely frames as sinister despite its seriousness, might be a way of taking refuge. “Scientists get on with it and try to make something work. I have a trust in those impulses.”

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments