Champagne reaches extremes, sweet and dry

Simply sign up to the Retail & Consumer industry myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

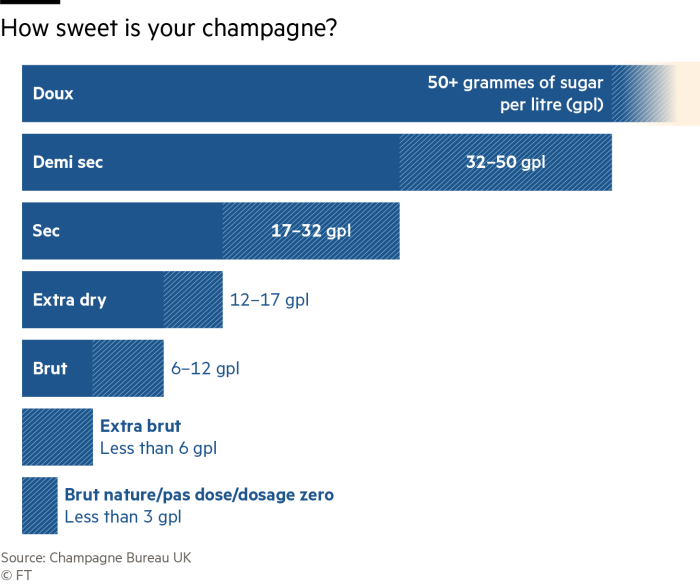

It might seem surprising that even champagnes labelled brut (dry) have sugar added — 6g-12g per litre are allowed by convention, in fact. In the Champagne region, grapes struggle to ripen and thus sweeten, so the wines are searingly dry without intervention. Bollinger Special Cuvée Brut, for example, has a dosage — the level of sugar added — of 8g-9g per litre.

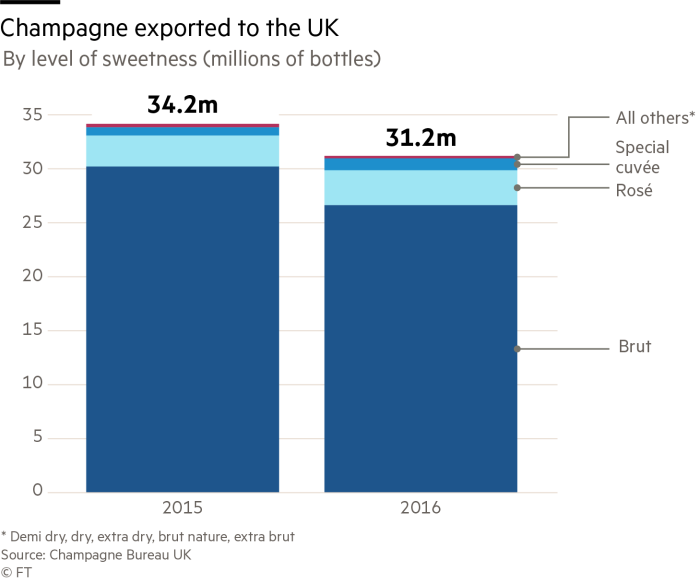

Brut champagne is overwhelmingly the most popular kind: 85 per cent of champagne sold in 2016 in the UK, according to the Champagne Bureau UK trade body. But at the edges of the market, two opposing trends have emerged in recent years: growth in the driest champagnes — and the sweetest.

At the dry end are champagnes known as zero dosage, brut sauvage or ultra brut, with only up to 3g of sugar added. In April this year, Veuve Clicquot released its first extra brut champagne, the non-vintage “Extra Brut Extra Old”. It is an appealing wine: the softness and mellowness of its age decrease the need for sugar. Critics and consumers have warmed to it. Jamie Goode, who runs WineAnorak.com, applauded its “lovely precision”, declaring it “really gastronomic and structural”.

Notable non-dosage wines (some with no added sugar at all) include Ayala Brut Nature, Tarlant Rosé Zero Brut Nature, Louis Roederer Brut Nature and Drappier Brut Nature Zero Dosage. They are superbly crafted wines that make invigorating aperitifs and partners to simple food such as a plate of oysters or smoked salmon. This is still a minuscule part of the market, however: 52,000 bottles out of 31.2m sold in 2016, or 0.2 per cent.

Partly this development is a response to environmental conditions: as climate change has meant warmer summers in Champagne, grapes are ripening more and thus are sweeter than of old. “When I started at Pol Roger 20 years ago we used around 12g per litre in our Brut NV [non-vintage],” says James Simpson, managing director of Pol Roger Portfolio champagnes. “These days we use 9g per litre. This is partly because of better ripening but also because we age the wine a bit longer, meaning that it’s drunk at a much better stage of maturity.”

At the sweet end are the rich or doux champagnes, which can have over 50g per litre of sugar added — unpalatable to traditionalists but popular as a mixer in cocktails. Terminology here gets blurry: some producers call their champagnes “rich” even if they are technically demi-sec (32g-50g). Sugar can cover faults in sparkling wine and some unscrupulous champagne producers — none mentioned here — have been known to add plenty to mask a wine’s defects.

Moët & Chandon launched Ice Impérial NV in 2011 and its Ice Impérial Rosé NV in 2016, both made especially sweet so that they can be drunk over ice beside the swimming pools of the Riviera or in the nightclubs of New York. They each have 45g per litre of sugar. “The dosage has been deliberately and carefully chosen to give the wine its structure and personality,” explains Moët winemaker Benoît Gouez, “and to help create and maintain the champagne’s perfect balance when it meets ice cubes. I believe that it’s the dominance of pinot noir and pinot meunier in the blend that really gives this champagne a richness that the presence of ice actually amplifies.”

Traditionalists might bristle at the thought of champagne being drunk with ice cubes but many argue that there is a place for such wines. “Moët over ice might appal the purists,” says wine writer-turned-merchant Chris Orr of the Brighton Wine Company. “But if it tempts people back into spending a little bit more on their fizz and opting for champagne, it can’t be a bad thing. Besides, up until a century ago nearly all champagne was sweet. It was consumers in the UK who started demanding drier styles in the 1920s.”

Besides, although the diet-conscious might favour low-calorie bone-dry champagne, sweet champagne has its role too. Take Pol Roger Brut Réserve NV: it is without a doubt one of the best non-vintage champagnes you can buy. But have you ever tried it at a wedding alongside the cake as you toast the bride and groom? It is a disastrous match, the sweetness of the cake making the champagne taste uncharacteristically acidic.

That is where Pol Roger Rich NV comes in. The wine is exactly the same as the Brut Réserve NV (one-third chardonnay, pinot noir and pinot meunier grapes, blended from 30 or more base wines) except that it has a dosage of 34g per litre; the Brut Réserve NV has 9g. “We sell more Pure [extra brut] in the UK than we do Rich, it’s true,” says Mr Simpson. “But that’s partly because we don’t make a big thing about the Rich.”

This spectrum of dosages reflects the subtle ways in which the industry of champagne making is coming to terms with modernity. It also means that now is a great time to be a champagne lover, with wines to suit every palate.

Tasting notes, from dry to sweet

Tarlant Rosé Zero Brut Nature NV (0 grammes of sugar per litre)

There is so much luscious pinot noir fruit here that you do not notice the absence of any added sugar.

Veuve Clicquot Extra Brut Extra Old NV (3gpl)

Brand new release from VC and formidably fine, made from the reserve wines of six different vintages.

Pol Roger Brut Réserve NV (9gpl)

The “White Foil” fizz is as finely crafted a non-vintage champagne as you will find.

Taittinger Nocturne Sec NV (20gpl)

A balanced and nuanced champagne whose subtle sweetness is beautifully judged.

Moët & Chandon Ice Impérial NV (45gpl)

Moët’s novel take on sweet champagne is designed especially to be drunk over ice.

Comments