Francesca Amfitheatrof’s 21st-century cave

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Francesca Amfitheatrof, the always impeccably groomed artistic director of jewellery and watches at Louis Vuitton, is not the first person one would expect to find barefoot in a cave – and smiling about it. But here we are, on a breezy pink-and-gold September afternoon, in the sparsely populated south-western end of the minuscule island of Ventotene (2.8km by 880m). Amfitheatrof, sans her Birkenstock 1774s, is padding around a grotto on the side of a bluff, happily expounding on its every curve, cubby and extrusive boulder.

Granted, this is not your run-of-the-mill cave. The stone ceiling, arching in an uneven half-arc over the space, is painted white; towards the back, it veers up to a glass-enclosed natural opening through which diffuse sunlight spills. Two walls meander in desultory curves down the sides of the space: a built-in lounging bench hugs one of them, while a fireplace has been fitted opposite, its pale pinkish-grey brick interior a moment of softness. Surrounding it, in a semi-circular embrace, is a sunken living area. An open kitchen at the cave’s centre forms a horseshoe curve, its countertop clad in the same cement-hued terrazzo that covers the entire floor. This imparts the subtlest pleasing texture underfoot – almost, but not quite, roughness. I stand at the space’s centre and cannot find a single straight angle.

Holiday homes are meant to take you away from the dreary prosaics of the day-to-day – and you can’t get much further from the bustle of the 21st-century professional designer’s life than a cave in a cliff formed during the Plio-Pleistocene era. Yet Amfitheatrof’s cave is entirely modern, and entirely her: over the several years she has been restoring it she has brought her sharp eye for form and proportion to bear on every inch of its 150sq m. She has smoothed surfaces, incorporated structure and layered in material and chromatic softness – but only as much as is absolutely necessary. Like a judiciously cut gem – and the understated yet striking jewels Amfitheatrof herself designs and gravitates toward – its elemental nature is enhanced by a minimalist intervention. “I haven’t really decorated it much,” she says, “because it doesn’t really need it.”

Amfitheatrof may not have always envisioned a cave as her vacation bolt hole, but Ventotene, one of Italy’s Pontine Islands (of which Ponza, about 25 miles to the north-west, is the best-known), was always on the list of the places she might one day have one. She spent the summers of her peripatetic youth with her cousins on the island (her mother is Italian, her American father was a Time magazine bureau chief working variously in Japan, Russia, Rome and London). Today, those cousins own and run Agave e Ginestra, the charming hotel just below Amfitheatrof’s front garden. “Back then there was no hotel; for years it was all a very hippie-campsite situation,” she tells me. “When I was older, living and working overseas, I didn’t come here for quite a while. But about 10 years ago, I brought my husband [the investor and entrepreneur Ben Curwin], and we saw this and became obsessed with it.”

It was a technically complicated road from love at first sight to liveable space. “We had to first make it geologically sound before anything else. So we did a ton of work up there,” she says, pointing to the whitewashed stone above us. “But because the entire island is protected [it is a European Heritage Label site], almost any alteration was prohibited.” To manage the project, she enlisted Francesca Capitani and Marco Lanzetta of Roman architecture firm LaCap. “They’d done some houses in Ponza – though never a cave before. But they really understood what I wanted: a clean entrance and very few materials.”

Working alongside them were Francesco Mancini, a geometra (structural engineer), and a second architect, Monica Fasano, who facilitated approvals – often the most fraught part of any Italian restoration project. (“But coming from a more Anglo-Saxon culture, I wanted everything to be absolutely above board.”) But the real genius, she says, was her builder, Giulio Sensi – nickname: il professore – who doggedly brought all the ideas to fruition while actually living on site for several months.

The team spent the first year or two installing multiple steel H-beams, steel rods and structural nets. “We drilled into the rock like a cheese and created this support apparatus,” she says. A state-of-the-art heating-cooling-ventilation system was also put in. The natural hole became a skylight, with custom-built electronic window panels and blackout blinds. All of this was done while Amfitheatrof was living in New York and then Connecticut, travelling for work (besides her role at Louis Vuitton, for which she commutes regularly to Paris, this year she launched Pauer, a unisex customisable line of bracelets in gold and silver) and, during the pandemic, managing the project via WhatsApp. Add to this the considerable difficulty of getting materials and shipments onto the island, even from Rome, and there were, she says, more than a couple of “oh God, what have I done” moments. The result is “a place that is solid” – as well as warm in winter, cool in summer, and remarkably devoid of damp.

It is also quite magical. The three bedrooms are alcoves, each with a raised sleeping platform – the chicest imaginable permutations of a cubbyhole, the beds layered in linens from Puglia’s Tessitura Calabrese and custom-made Loro Piana cashmere blankets. The two smaller ones belong to Amfitheatrof’s children, Niko and Stella May; the master is behind the kitchen. All of the storage was designed by Tree, a Rome-based woodworker. The bright-white cabinet and closet doors are covered in a white-on-white circle pattern of Amfitheatrof’s own design created with a high-shine varnish: “At times it’s almost invisible, and at times pronounced, depending on the light.”

Almost directly beneath the skylight is the cave’s freestanding bathroom, whose walls extend only halfway up to the stone ceiling, echoing its uneven curve. Getting this right, she says, “was the hardest part to envision about the whole project. We had to really think about how to make something that didn’t just look like you’d added some weird structure.” She shows me inside: the loo to the left (with Niko’s Lego masterpieces as decor), shower room to the right, and a central, light-flooded space with a wide basin.

The internal kitchen looks more like an entertainment bar. “Everything is electric because of fire risk, so it all had to be the latest technology,” Amfitheatrof says. “To be honest I didn’t really want an indoor kitchen, but everybody convinced me I needed one for winter.” She leads me outdoors to admire its alfresco counterpart, which runs flush along the curve of the garden wall: cook-top, barbecue, large sink, a pair of fridges hidden away behind curtains made from a twill from Loro Piana’s boating line (in fact, all the cushion and cotton fabrics are Loro Piana all-weather ones). In the garden, a large oval cement dining table’s surface is also covered in that warm terrazzo. Jaunty white-and-blue cushions and throw pillows line the banquette behind it.

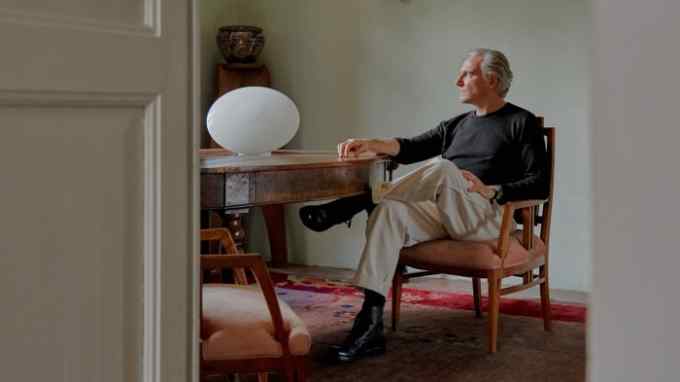

Inside and out, the furnishings are notably few – but the mix of eras, styles and materials results in plenty of character. “I found this amazing woman in Turin, Ortensia Compansa, who sourced a few really great pieces for me from the vintage market there,” Amfitheatrof says. Among these are a ’70s wicker palm tree floor lamp by the Mexican artist Mario Lopez Torres; and a set of sculptural, modular 1977 table lamps produced by the Japanese manufacturers Yamagiwa. The smattering of vintage rattan and bamboo chairs in the garden, designed by Rohé Noordwolde, came from the Dutch auction website Catawiki. Elsewhere, Amfitheatrof looked to Soho Home – for the buttercream-finished side and coffee tables (used both in the cave and in the garden), as well as the nubbly Garret armchairs, the rattan pendant lamp above the kitchen and a natty little brass drinks trolley.

In the early evening, the trolley finds its way out onto the front patio, where we sit and admire Rome-based landscape architect Luca Catalano’s handiwork with native species in the garden – Holm oaks, low date palms, various flowering shrubs and grasses. She tells me he’s recently won a commission to re-landscape Santo Stefano, a much smaller Pontine island 2km offshore, clearly visible on the horizon; once a Bourbon stronghold, complete with prison, it’s now part of a protected national park. She describes the network of cisterns created two millennia ago on Ventotene by the Romans to harvest rainwater, and the legacy of Giulia Maggiore – Julia the Elder, the only biological child of Caesar Augustus, who was exiled to the island and died there. She extols the food at Un Mare di Sapori, down in the old Roman harbour, and laughs about raiding her cousins’ organic vegetable garden at the end of her path. The sun tips lower towards the rosy sea; there’s no sound but the wind. Behind us, the volume of her cave beckons: a gem left just rough enough, unlike anything on the island, or anywhere else.

Letter in response to this article:

Tame by the standards of Manrique’s lava field cave / From Deip Guha, Keswick, Cumbria, UK

Comments