Supercar designers share their eureka moments

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

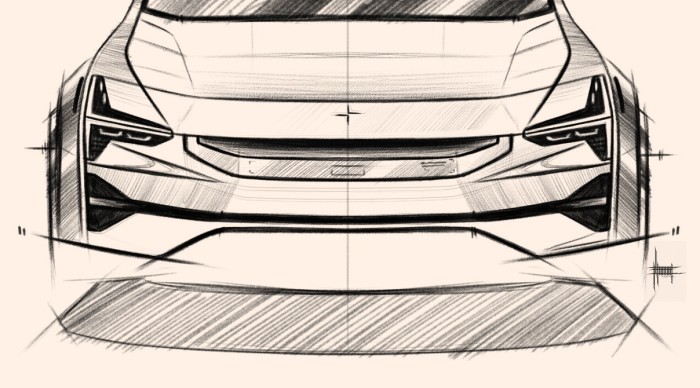

The grille

Maximilian Missoni, head of design at Polestar

Missoni worked at Volvo Cars as vice president of exterior design for more than six years before moving to electric car maker Polestar. It’s no surprise that he wants to talk about the front grille. In electric cars, which don’t have an internal combustion engine under the bonnet, the grille is basically redundant. Nevertheless, a grille is as much about aesthetics as practicality. It defines the “face” of a vehicle, and many brands shifting into electric have retained a fake grille in their designs. “It’s a very sensitive component to touch and that is why many companies have decided in the electric transition to maintain the historical hallmark of a grille but block it off or black it out,” he says. “In the case of Polestar, it’s a little bit of the opposite because we don’t have that kind of history and we can start from scratch.”

Actually the Polestar 1 and 2 did have a grille, but the redesigned Polestar 2 and the Polestar 3 SUV have ditched it in favour of a panel in the same colour as the rest of the car. It’s called the SmartZone and, as Polestar puts it, it repurposes the front of the car from “breathing to seeing”. If you peer at the front of the Polestar 3, the heating wires are visibly clustered together with the front-facing camera, radar and accelerometers. Missoni explains: “We know that we need heating systems and we don’t hide them any more. We bring them to the surface. Now what you want to do is to show off the technology you’re carrying around in a vehicle. The SmartZone offers the chance to present and celebrate a vehicle’s technology.”

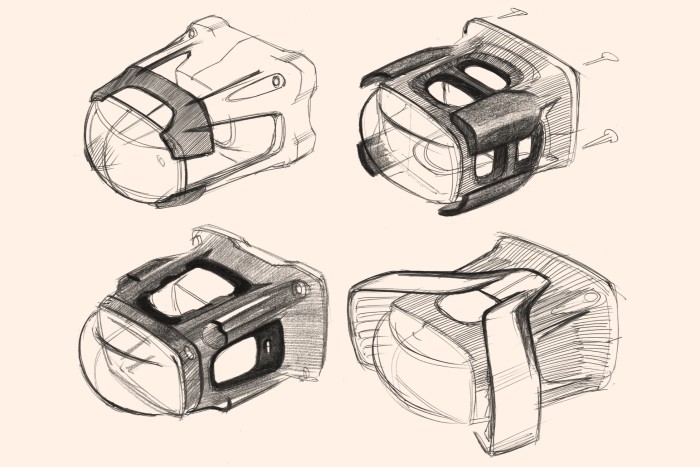

The headlamp

Marek Reichman, executive vice president and chief creative officer at Aston Martin Lagonda

During his time at Aston Martin, Marek Reichman has designed many of the cars James Bond has used to evade villains, including the DB10 in Spectre that was a foretaste of the current Vantage. He’s also the creator of the current DB11 and DBX SUV models. But his obsession? The headlamp.

“The shape of a headlamp is one of the identifiers of the brand. It’s a huge signifier of the personality of the product,” says Reichman. “The headlamp is safety-critical and one of the most complex items on a car because there’s so much legislation that goes into it.” As a piece of design, the headlamp is an incredibly labour-intensive and costly bit of kit. And that’s what Reichman wants to circumnavigate. “Here’s my sketch of the latest technology to produce lamps in a much shorter time period. We are now using 3D printing instead of injection moulding.”

According to Reichman, 3D printing foresees a future where traditional manufacturing processes are upended and it will be much easier to upgrade your car. “The headlamp is a very interesting component to look at because its design has been fixed for a long time and the development of a new headlamp runs into tens of millions for a mass manufacturer. If you can 3D-print something, you are able to change more quickly and cut that cost by a factor of a hundred. As technology changes we may not have to wait five, six or seven years for the refresh of the cars. It may happen far quicker.” He continues: “3D printing also means we can reduce weight. An average headlamp even in a sports car is 3.5kg. A 3D-printed Valkyrie headlamp is 1.95kg. And with the forthcoming hybrid Valhalla, we’ll be using the same process and maybe there will be an option to choose either twin headlamps or the single headlamp.”

It opens up a future where there will be much greater scope for an owner to individualise a car part. “Part of the designer’s role is to work to a brief. That’s why people go to Savile Row. You go in with a view – this is who I am. This is who I feel like. This is how conservative or flamboyant I am. And you explain that to your cutter or tailor or dressmaker.”

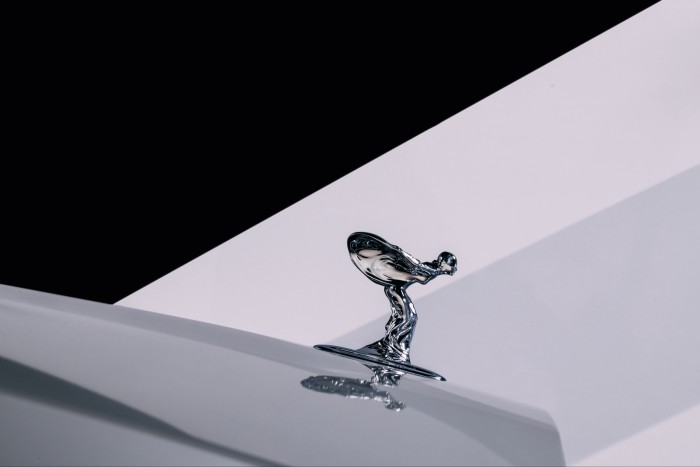

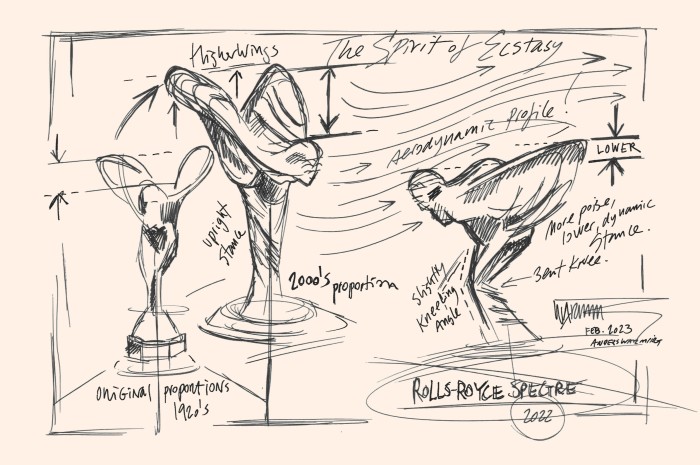

The Spirit of Ecstasy

Anders Warming, design director at Rolls-Royce Motor Cars

During the wind-tunnel development of the brand’s first all-electric car, the Spectre (out later this year), the engineering team noticed something curious in the way the Spirit of Ecstasy mascot carved its way through the air. “We found out that the wings of the Spirit of Ecstasy were creating more turbulence than was really necessary,” says Warming.

The Spectre is a crucial car for Rolls-Royce. It unlatches the future of electrification for the company while ensuring it still looks like an imposing Rolls-Royce with its prominent figurine mascot. The Spectre spent 830 hours in the wind tunnel and achieved a slippery drag coefficient of 0.25cd – the most aerodynamic Rolls-Royce ever produced. “As the wings of the Spirit of Ecstasy were blocking air we redesigned it,” says Warming. “They are not as upright and it helped us guide the air over the car.” The Spirit of Ecstasy’s fluttering robes have been updated. She has also taken on a more forward-facing stance, with one leg slightly in front of the other as though braced for the headwind. Take a closer inspection and it’s noticeably shorter at 82.73mm tall.

The figurine was originally designed by sculptor Charles Sykes and based upon actor Eleanor Velasco Thornton. Over its 112-year lifespan, the figurine’s shape has evolved: it has been rendered in various sizes, materials and stances, including a kneeling position. For the Spectre, Rolls-Royce found itself going back to Sykes’s original. It had a flatter wing profile and it was the eureka moment, says Warming. “We could factually say the past already gave us a solution.”

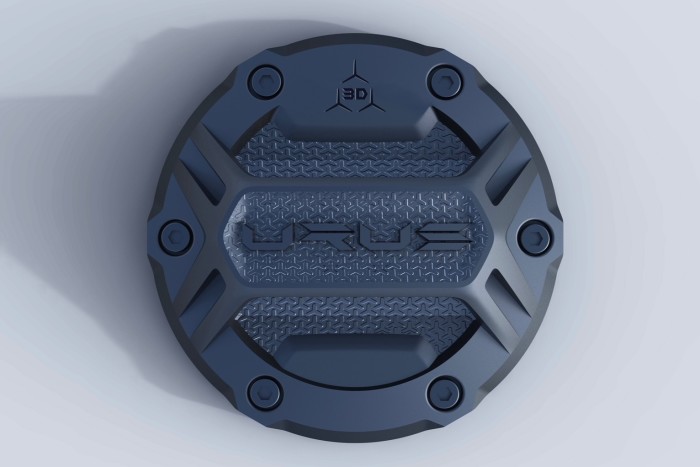

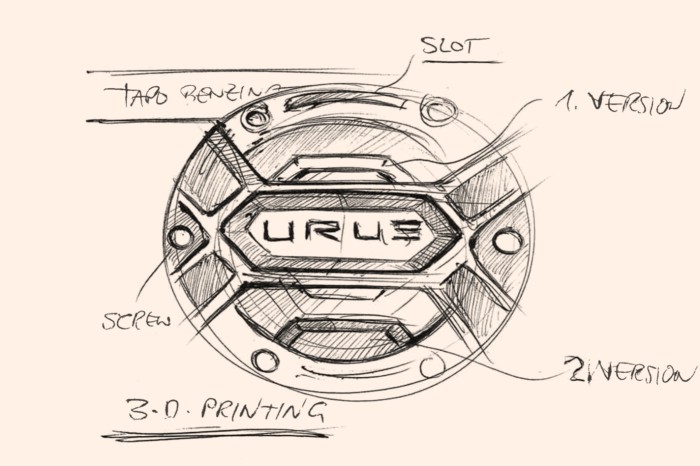

The fuel cap

Mitja Borkert, head of design at Automobili Lamborghini

As head of design at Automobili Lamborghini, Borkert is in charge of the visual lexicon of what is, arguably, the most flamboyant of all the Italian super-sports-car makers. But which component does Borkert earmark for an overhaul? The humble fuel cap on the Urus, a Super Sport Utility Vehicle.

Like Reichman, Borkert is excited to see how 3D printing might revolutionise design, allowing Lamborghini to add smaller bespoke components on the cars. “On the Urus we have started with a plain plastic fuel cap and there’s an option of a carbon-fibre fuel cap. It gave us greater design freedom and potential for increased personalisation.”

Car makers always balk at large capital investment when retooling an existing production line for any new generation of model or mid-life refresh. With 3D printing, they can develop small parts that need “no tooling or investment costs”. As all 3D printing is done in layers, the finished product has a patterned moiré effect. “On the Urus I have put the name Urus and small epsilons in areas where the moiré effect would disturb me,” says Borkert of the manufacturing limitation. “The effect looks like the polishing on a watch.”

It’s just one small step, he says, towards greater specification: “Bespoke customisation could be absolutely possible.” One suspects the Urus fuel cap is simply a toe in the super-sports car’s future.

Comments