UK gender pay gap research heightens concern on corporate laggards

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

UK employers which reported their gender pay gap information late were more likely to produce inaccurate figures than those that filed on time, according to analysis by the Financial Times.

The finding came after the Equalities and Human Rights Commission, the body responsible for enforcing the gender pay gap reporting requirements, said it would start proceedings against 500 employers which have failed to file any information.

All UK employers with at least 250 employees had to report their 2017 gender pay gaps under government legislation.

Public sector employers had to report 14 data points — including their mean and median hourly gender pay gaps, and the proportions of men and women in four remuneration bands — by the end of March. Companies and charities had until April 4.

The Financial Times analysis shows that 13 employers, or 2.2 per cent, of the 585 which have reported after the deadline said they had a mean and median pay gap of exactly zero, a result that is statistically highly improbable.

By comparison, only 0.5 per cent of employers that reported before the deadline had the same questionable figures.

The FT analysis also shows 22 per cent of employers which reported late had both mean and median gender pay gaps that were whole numbers, a result that is statistically unlikely. Only 14 per cent of employers which reported on time recorded whole numbers for both measures.

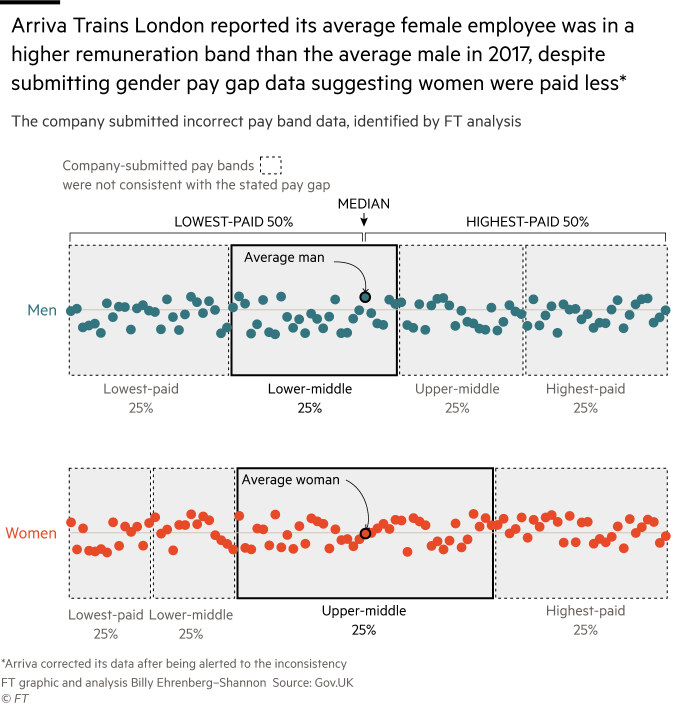

Meanwhile, 486 employers, 4.6 per cent of all those which have filed information so far, have reported median pay gaps that appear to be inconsistent with their remuneration bands.

Of the employers which reported late, 7.7 per cent had this issue, compared with 4.4 per cent of those that filed on time.

While the information on median pay gaps may be accurate for employers where large numbers of the workforce are on the same hourly rate of pay, some inconsistencies have revealed reporting errors.

The Law Society, whose data showed these inconsistencies, said that when it filed its figures, the remuneration pay bands were “unfortunately published in reverse order”. “We will be clarifying our figures with the government,” it added.

Figures from all 21 entities within the Arriva transport group also highlighted inconsistencies between median pay gaps and remuneration bands. Arriva said it had taken steps to correct the problem.

G4S Cash Solutions said its figures were correct and the apparent inconsistency was explained by large numbers of its staff being paid at the same hourly rate.

All three organisations reported before the deadline.

The Government Equalities Office, which manages the portal where gender pay gap data are registered, originally estimated that a total of 9,000 employers were covered by the new reporting requirements. Employers with less than 250 staff could also choose to report voluntarily.

On Friday, a total of 10,504 employers had reported, with a median pay gap of 9.3 per cent. Construction, finance and insurance, and education were the worst performing sectors, with gaps of 25, 22 and 20 per cent, respectively.

Rebecca Hilsenrath, EHRC chief executive, said last week that it had contacted almost 1,500 businesses in April which had failed to register their gender pay gap data by the deadline, and was now investigating 500 of these.

“Breach of these regulations is breaking the law and we’ve always been clear we will enforce with zero tolerance,” she added.

Employers which remain in breach of the regulations could face fines and potential court action.

The number of employers which are in breach raises concerns about the ability of the EHRC to enforce the regulations effectively.

In February, the EHRC said it had requested £300,000 in this financial year to cover five staff members and a legal counsel to police the rules.

Ross Meadows, a partner at Oury Clark, a law firm, said that many employers had found the task of compiling gender pay gap data to be complex, while others, such as those using casual staff, believed they were not subject to the rules.

But he added that the main reason for non-compliance was that the rules were seen as “toothless”.

Mr Meadows said he believed that employers were not concerned about the likelihood of unlimited fines, since the EHRC had made assurances that this would not be the first step.

Comments