High Art gallery is flourishing in Paris’s effervescent scene

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“We had no money, no backers, we started with nothing,” says artist Jason Hwang about how he and curator Romain Chenais opened a project space in Ménilmontant, a popular district in Paris next to the Père Lachaise cemetery, in 2011. Two years later, joined by gallerist Philippe Joppin, they founded High Art, now one of Paris’s most exciting galleries.

High Art, which is showing in the Paris+ par Art Basel fair next week, “appears to be the most dynamic of the galleries that have flourished in Paris in the past decade”, says art critic Henri-François Debailleux.

“We thought we had to move from a project space to a gallery in order to accompany the artists,” says Joppin, previously a director of Perrotin gallery in Paris. “We weren’t satisfied by one-shot shows; the artists need to know we are committed to them long term. And we like to have several exhibitions over time with them.” They branded it High Art because they did not want to use their names and they wanted to emphasise the international vision of the gallery. It is also an allusion to the long debate about art versus craft.

High Art now represents 25 artists from different parts of the world, including some they have introduced to France. Rachel Rose, Valerie Keane, Max Hooper Schneider, Laure Prouvost and David Douard were offered early solo shows. Prices range from €5,000 to €70,000, although some installations reach €100,000 or more. In 2020, High Art also set up a branch in Arles in the south of France, which is home to several art foundations.

The headquarters, though, are now established in Pigalle. The gallery moved there in 2017, setting up in the building where Georges Bizet wrote his 1875 opera Carmen. Apart from a few pockets, Pigalle is no longer the red-light district it used to be. Rather, it has revived its image as the birthplace of Romanticism, inhabited by musicians, painters and writers in the 19th century and referred to at the time as “the new Athens”. Pigalle is quite separate from the trendy Marais quarter where contemporary galleries have prospered, but the gentrified atmosphere there did not appeal to the High Art team.

Joppin wants the gallery to be a venue where collectors could be tempted to visit after a first encounter with High Art, often at a fair. Participating in global events has always been a driver for High Art. “We need these events to meet collectors who come to us to discover new forms of art,” Joppin says, adding that 80 per cent of their sales go abroad. High Art started in the emerging-gallery segments of these fairs, but has now found its place in their main sections.

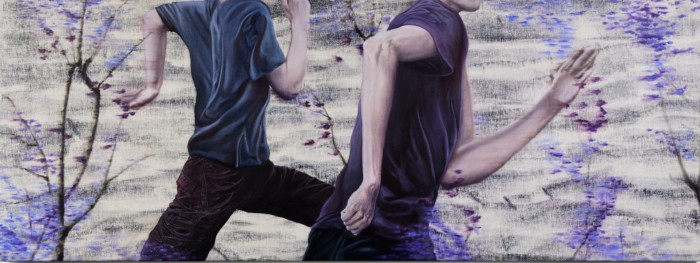

At Paris+ the gallery is showing figurative works from a group show (including Keane, Julien Creuzet, Mélanie Matranga and Orion Martin), mirroring a selection of abstract works presented at Frieze in London the week before. In Pigalle from October 19, High Art will welcome the work of London-based artist Michael Ho, who paints images on the back of the canvas.

“I was happy to work with High Art because, among the younger galleries, they have the strongest international aura, and I knew they were the right spokespeople for my message in these big venues,” says Creuzet. Raised in Martinique, he will represent France at the 60th Venice Biennale next year. In 2019, his first show at the gallery featured splashy coloured installations made of recycled material and drew attention to the poisoning of French-Caribbean people due to a pesticide used in banana plantations for two decades. The Possessed of Pigalle, his second exhibition last spring, evoked a Vodou temple in the district.

British artist Matt Copson had his first exhibition in France at High Art in 2016, before a “very ambitious show” in Pigalle, “a kind of three-part opera inspired by Bizet”, during the difficult time of long lockdowns. “We have had a very close relationship from day one,” he says. “There is a constant dialogue. They are not market-driven. And it was very important to be able to deal with three people on equal basis. With one we can talk about mechanical practicality and, with another, dive into the conceptual nature of my practice. This kind of relationship is very rare.”

Chenais believes the “Parisian art scene has become much more effervescent. When we started, big collections were state-run — very much top-down. Now private collectors and foundations, starting with Arnault and Pinault, are present in the city and this has an impact on all layers of the market — and the way people look at young artists and galleries.”

After Brexit, adds Joppin, several British galleries opened offices in Paris or even moved there. He reckons, though, that post-Covid times are weighing on the business: “In Paris, the art market has always had low seasons and high ones, but the lowest ones seem to drag on a bit longer now.” What he feels the need for is “the rise of a new, strengthened generation of French collectors” to maintain the impetus in these uncertain times.

Comments