Past winners share how FT award advanced their cause

Simply sign up to the Sustainability myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Gaetano Lapenta founded his Milan-based company Fybra in 2021, to solve a personal challenge: poor indoor air quality faced by his daughter and many other schoolchildren. Fybra makes a device that detects when the quality of air in a room is below par — a factor in to illnesses ranging from asthma to heart disease — and changes colour to indicate a window should be opened for ventilation.

Since Lapenta was honoured as an “alumni change maker” in 2022’s FT Responsible Business Education awards, Fybra has witnessed significant growth. From a venture whose products benefited 40,000 people, mainly in schools, two years ago, the company has expanded, reaching more than 300,000 people, including those in offices and homes.

The FT award not only boosted visibility but also led to unexpected partnerships with large corporations and collaborations with public authorities, the company says. This propelled Fybra’s international expansion into Germany and across Europe.

“We had no intention to expand globally but, after receiving recognition and visibility through the award, we received numerous requests from European countries,” Lapenta says. “So we collaborated with energy utilities, which integrated our solution into their services and, as a company, we secured public grants from municipal governments like Hamburg, allowing us to successfully scale our impact.”

Fybra was co-founded by chief executive Lapenta after he hit on the air monitor idea during his executive MBA at Italy’s Polimi Graduate School of Management. He is among an ambitious cohort of “alumni change makers” who have gone on to make a wider impact across diverse domains.

The start-up’s growth since 2022 has seen it hire more staff and secure patents through investments in research and development. These include advances in sensors and algorithms for small spaces, as well as the development of products for large buildings with mechanical ventilation and energy-efficient heating systems.

It has not been all easy. Lapenta acknowledges the challenges of building credibility internationally, overcoming cultural obstacles, and countering about foreign technology providers. Fybra managed this by demonstrating a commitment to investments, including those in human capital, in these countries.

“Even with a strong record of 100,000 paying customers and patents, you still face cynicism abroad,” Lapenta says. He advises enterprises seeking global impact to prepare for international development early. “We were not ready for the major exposure we got after we won the FT award.”

As well as technological innovations such as Fybra, the “alumni change makers” award has recognised ventures driving impact in other fields. Elisa Dierickx, who played an important role at Fundação Maio Biodiversidade (FMB), a nature conservation non-governmental organisation in Cape Verde, has seen significant developments since winning the FT award two years ago.

Those include receiving the National Medal of Merit from the president of Cape Verde and opportunities such as speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos. These developments have helped garner support and provided a platform for spreading FMB’s message about protecting wildlife, habitats and natural resources.

Dierickx, who has an MBA from Insead, underscores the need for intrinsic rather than financial motivation, and engagement with diverse stakeholders, including businesspeople and politicians, to overcome challenges in changing mindsets. “These awards are platforms that increase our credibility,’’ she says. ‘‘When you have major economic and political institutions behind you, people don’t see you as tree-huggers anymore.” She adds that this has brought new potential funding opportunities.

Academic research also takes centre stage in the FT’s Responsible Business Education Awards. Fiona Marshall, a professor of environment and development at the University of Sussex Business School in the UK, won in the “academic research with impact” category in 2022 for her work on waste management in India. The research criticised centralised incinerators for undermining the livelihoods of waste-pickers and causing toxic emissions. Along with co-authors, she proposed decentralised solutions, collaborating with government and private sectors.

Marshall says the FT award helped to raise the profile of her work and served as a catalyst to broaden collaborations across academic disciplines and with external stakeholders, communities, NGOs and policy organisations. “These new links catalysed by the FT award are leading to exciting new collaborative opportunities,” she adds.

For example, she recently completed a project in India, funded by the British Academy and focused on the critical role that urban agriculture can play in supporting food security, livelihoods and wellbeing. “We demonstrate how current development trajectories are overlooking the opportunities to work with agriculture as part of a sustainable urban development strategy,” Marshall says. “Urban greening can be designed with a view to creating inclusive, multipurpose land use — and include agriculture,” she adds. “We are looking at the possibilities for this.”

She underscores the slow but significant impact of such work, gradually influencing policy and broadening perspectives. “These things are not quick — they’re all slow fuses but they’re important and, cumulatively, they come together and drive wider impact,” says Marshall.

Through her studies, she has developed recommendations for other academics on how to make a meaningful impact with research, beyond mere publication in top academic journals. She advocates for critical conversations on international collaborations, interdisciplinary research infrastructure, and career incentives in academic institutions.

“There’s a tension between doing impactful work and publishing enough to get promoted,” she says. “If we’re going to majorly accelerate progress on sustainable development and unleash what universities are capable of, we’re going to have to redefine incentives for career development.”

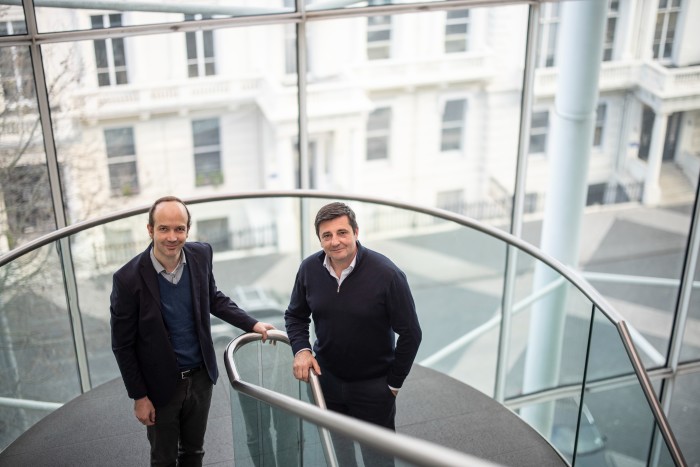

Enrico Biffis and Erik Chavez from Imperial College Business School in London — also 2022 winners in the “academic research with impact” category for their work on agricultural insurance in Tanzania — exemplify how researchers can drive impactful change. The study explored how integrating “parametric insurance” (which pays out a pre-determined amount based on the occurrence of a specific event) with loans can enhance financial inclusion for smallholder farmers in low-income countries.

Their initiative has influenced financial institutions in Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe, prompting the development of competing products and demonstrating uptake of the researchers’ ideas. “Our initiative garnered attention from major market players, prompting them to enhance the technical aspects of their insurance offerings by incorporating some of our findings,” says Chavez.

This had a positive impact on smallholder farmers. Biffis says: “Our work has contributed to a shift in loan underwriting practices. Previously, lack of collateral would lead to exclusion from the financial system. Our contribution, along with other factors, stresses the idea that technological adoption can mitigate risk in financial profiles. This concept is now more widely accepted and better understood than when we initially started our work.”

However, customisation for diverse market structures remains a key challenge in scaling such solutions, which underlines the importance of collaborations with financial institutions that work across borders. “There’s an element of customisation to the specific market structure, legislation, land rights, strategic crops and so on,” Biffis explains. His advice to others, is to be close to the problem owners, in this case the smallholder farmers. “That’s the only way you can truly understand what the bottlenecks are and how to fine-tune the solution on the ground.”

Comments