Xin zhong shi, and the rise of the made-in-China movement

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When designer Min Liu returned to China after spending seven years studying and working in Europe, the first thing she noticed was that women of her age were no longer wearing Chinese clothes.

To redress the balance, Liu launched the label Ms Min in 2010: it debuted with a 15-piece capsule centred around Chinese New Year. The collection – luxurious womenswear with thoughtful references to traditional Chinese fashion – made an instant impact, but not all feedback was positive. “Some people thought she was crazy,” says Ian Hylton, the brand’s president and Liu’s partner. “They said nobody wanted to look like that any more.”

Liu was ahead of her time. While the brand’s philosophy hasn’t changed, the market certainly has. Local social media platforms are now trending with phrases such as xin zhong shi (neo-Chinese style) and lao qianfeng (old-money aesthetic). In stylish restaurants and the pages of lifestyle publications, coveted Ming dynasty chairs and carved wooden sideboards appear alongside Scandinavian furniture, often reconsidered in sleek new forms. During a recent interview, Hylton was asked how he felt about the fact that his wife “literally created” the concept of xin zhong shi (he took it as a compliment).

Modern Chinese design is “buzzing”, says Licheng Ling, a Shanghai- and New York-based consultant and designer who launched Homeism, a loungewear brand inspired by traditional Chinese garments, in 2016. Her pure-silk pieces feature classical elements like mandarin collars and wide sleeves, but have a timeless, minimal feel. “Our generation and the [younger] generation are more confident about our own culture and traditional Chinese aesthetics.”

This didn’t happen in a vacuum. Donald Trump’s presidency and the US-China trade war in 2018 led to a surge in patriotism for both countries: in China this took the form of guochao (national wave). Consumers celebrated and shopped home-grown brands to an unprecedented degree (Korean beauty giants, which leaned on growth-driving mainland China at the time, are still feeling the heat), and local businesses touted sneakers and lipsticks with nostalgic and ostensibly Chinese branding.

But labelling the new wave of Chinese design as being nationalist is too reductive, says Bohan Qiu, who founded the Shanghai-based PR and digital content agency Boh Project. “It’s not just that. It’s a natural progression – you need to let people own their culture.”

China has long been an inspiration for foreign artists and designers. At the high point of western imperialism, Chinoiserie saw palaces in 18th-century Europe decked out in a mishmash of Chinese, Japanese and Indian art. Fashion has regularly borrowed eastern tropes: take John Galliano’s famous Christian Dior AW97 collection, or Prada’s spring-summer collections in 2003 and 2017 (which drew on significant motifs such as mandarin collars, cheongsam and silk-jacquard). Even Le Corbusier, Hong Kong-born gallerist Pearl Lam notes, was influenced by Qing-dynasty art. But despite its outsized impact, Lam says Chinoiserie’s influence in the west went virtually unnoticed by the culture it took from. “In Asia, we’ve always followed the western aesthetic. No one appreciated how strong Chinoiserie was.”

With that in mind, the current appetite for Chinese design feels all the more overdue. “China has a history of luxury that’s dynasties-old,” says Hylton. “Italian, French, American fashion, they’ve influenced our global vision for so long. It’s refreshing to have new cultures influence what’s happening.”

Qiu has observed this mindset shift in his team, which is largely Gen Z, known locally as Post-95s. “When I was younger, there was a big wave of people studying abroad and we were hungry for everything that was outside,” Qiu says. This dynamic has since shifted: “Young people don’t necessarily see something that’s from overseas as being better… they would see something that’s traditionally Chinese and reinterpreted in a contemporary way [as] being very cool,” he adds.

This was buoyed by local spending in retaliation to the March 2020 reports of human-rights violations in Xinjiang: a boycott of global names such as Nike and Adidas ensued after the brands pledged not to use suppliers in the region, which in turn saw an increase in spending on local brands such as Anta and Li Ning. By July 2021, Anta’s market value exceeded $60bn and Li Ning had already seen its shares jump more than 84 per cent.

Sarasvati, 2022, by Jiang Sheng

Qilin by Xi Xing Le

These instances, however, merely foregrounded a wider shift towards local talent. Designer Samuel Gui Yang references ’90s Cantonese pop culture with sharp-shouldered tailoring and shirts that recall the “water sleeves” one might see in Chinese opera. In the homewares space, Xi Xing Le, a Shanghai-based brand, reimagines Kwon-glazed porcelain through a contemporary lens – think candles mimicking carved ivory landscapes and a rendition of the qilin, a mythological Chimera-like creature, in a Y2K-pink colourway. In contemporary art, names to know include Jiang Sheng: a young Xiamen-based artist continuing the art of Buddha sculpture: the sleek proportions of each piece give them a weightless, surreal feel.

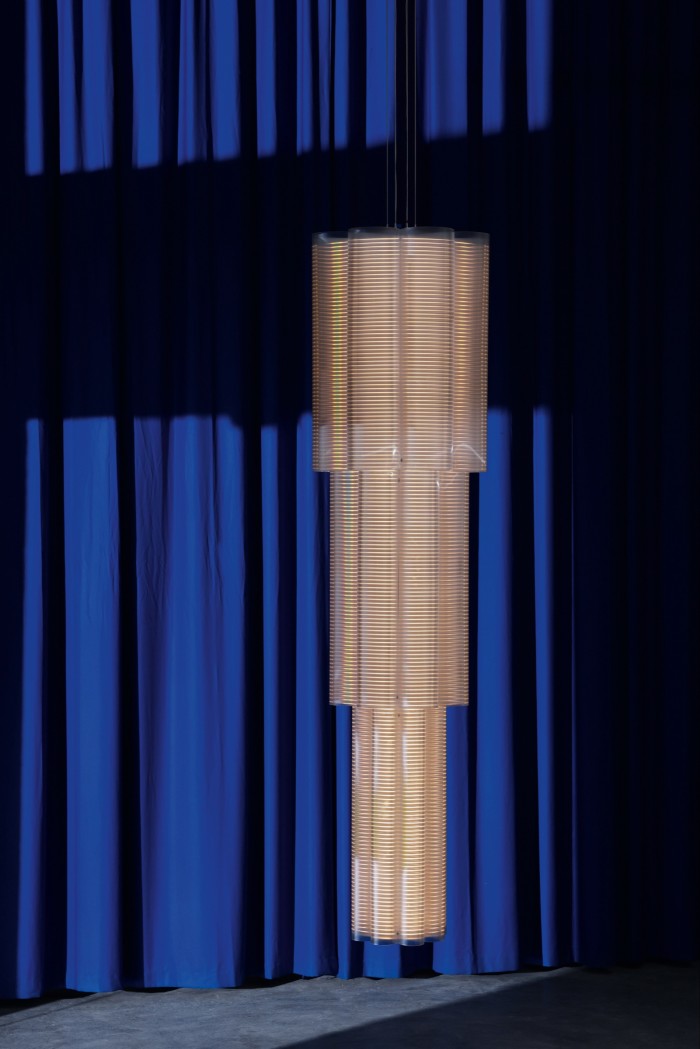

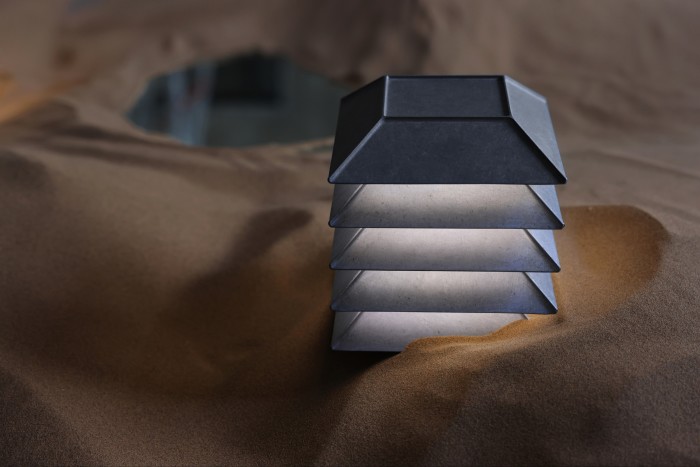

To Qiu, xin zhong shi not only dovetails with the rise of quiet luxury, but signals the evolution of guochao through more elevated and nuanced interpretations of Chinese culture. “It’s becoming deeper and deeper – it’s not just a dragon pattern or the colour red.” He points to Soft Mountains, a jewellery brand that’s finding inspiration in traditional accessories worn by ethnic minorities such as the Yi people, and working with indigenous artisans to realise their creations. There’s also Mario Tsai, a lighting designer exploring hidden light sources through styles such as the aptly named Pagoda, which was showcased at Milan Design Week in April.

But while xin zhong shi may serve to spotlight Chinese design both locally and internationally, the term can feel both vague and restricting. “Many aesthetic cues belong to China, because it’s so big,” says photographer Leslie Zhang, whose work references everything from Wong Kar-wai’s Chungking Express to landscape paintings. “Defining a new ‘Chinese style’ with such broad strokes also obliterates the diversity of our culture.”

Tethering xin zhong shi to traditional design cues also points to the challenges artists and designers face as they seek newness in a country so strongly rooted (and so strongly perceived to be rooted) in its 4,000-year history. “Whenever the world thinks of China, it falls into the dated feeling of it,” says Qiu, stressing that China is just as futuristic as it is traditional. “There’s anime, there’s sci-fi and LGBTQI drag culture. That’s also new Chinese.”

For all of the movement’s shortcomings, celebrating Chinese design still feels positive. Lam, for one, sees this as a turning point: “This is the period when many people are coming back to China and trying to find their identities,” she says. “This doubt is a great thing, because they’re not just blindly following, but looking for a Chinese aesthetic, creating a new one.”

Comments