Pearl Lam and Basma Al Sulaiman on their feisty, art-fuelled friendship

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

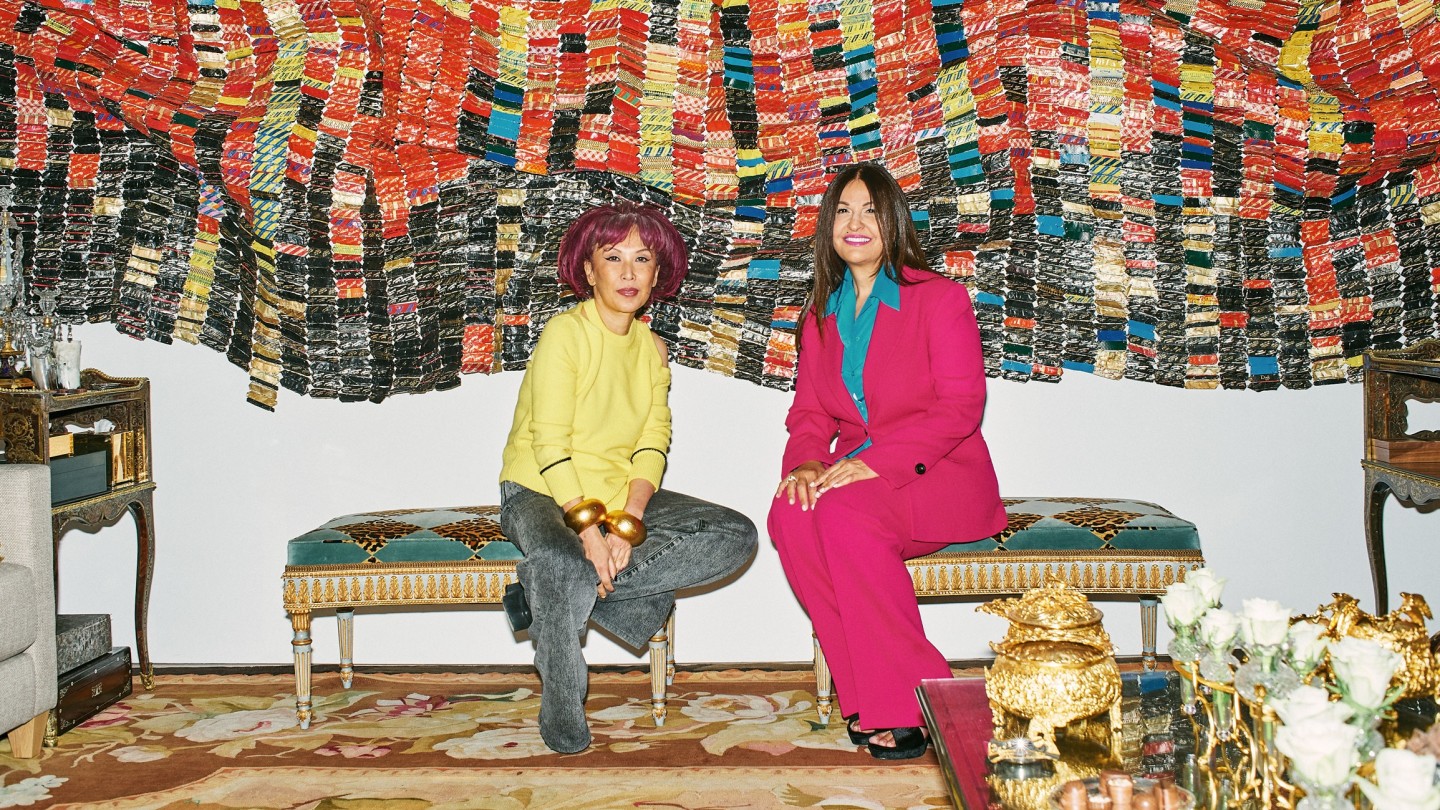

We met because Basma and one of my friends shared a divorce lawyer!” Gallerist Pearl Lam and her friend Basma Al Sulaiman laugh heartily as they sit in Al Sulaiman’s impressively appointed, art-filled London home. Lam recalls their first encounter around 2004 as they sip tea: “The lawyer introduced my friend to Basma and said, ‘If you collect Chinese art, you must meet Pearl.’”

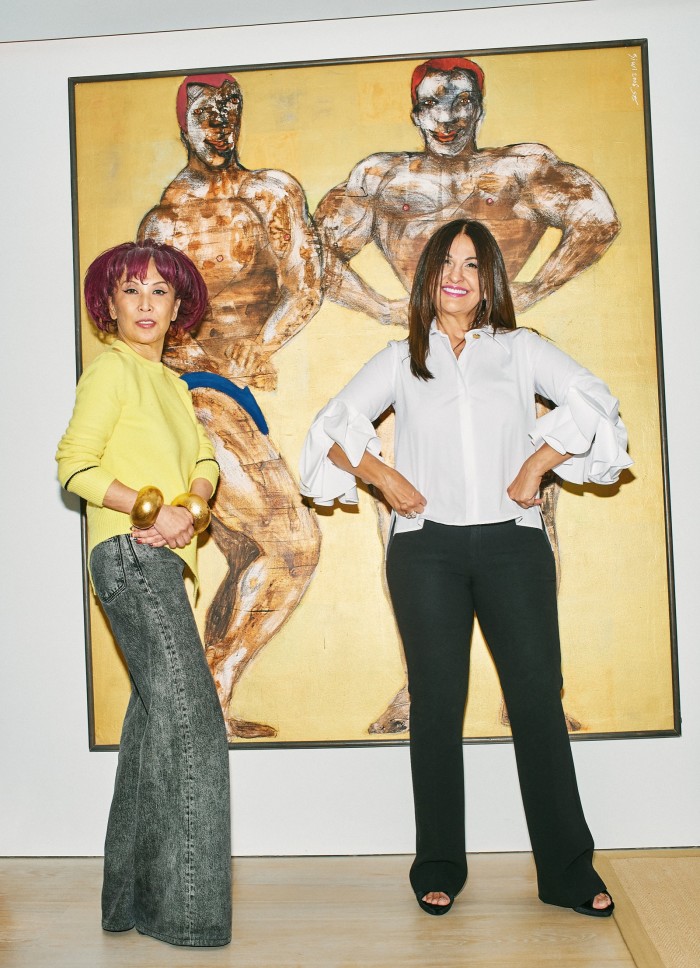

With her gravity-defying purple bob – paired when we meet with a lemon-yellow jumper – Lam has been involved in the Chinese art world for nearly 30 years. In 1993, she began collecting Chinese art; in 2005, she opened her first physical space in Shanghai and since 2012 has had a second Pearl Lam Galleries space in her hometown of Hong Kong, representing homegrown and international artists from pioneering Chinese abstract painter Zhu Jinshi to British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare.

Saudi Arabia-born Al Sulaiman, meanwhile, began collecting contemporary art in the 1990s. Her first purchase was a Hockney, and today she owns more than 800 works ranging from high-profile international artists such as Ai Weiwei, Tracey Emin and Andy Warhol to Saudi artists. In 2000 she moved to London and completed a diploma in modern and contemporary art from Christie’s Education. It was then that she became interested in Chinese art. “A Saudi collecting Chinese art!” explodes Lam. “You know? It was so strange to me. And she was buying political pop art.” She shakes her head. “I thought, ‘Why?!’”

“Because it was different from what I’d been seeing; it was fresh, it was human, it was real,” says Al Sulaiman, who has never worked with an art adviser and was introduced to Chinese art through a friend. “He called me and said, ‘Basma, there’s this amazing artist, I love his work but it’s too big for my house, would you be interested to see it?’” The artist was Beijing-based Yue Minjun, now famous for his “Cynical Realist” oil paintings depicting himself laughing, his face frozen in a demonic grin. Al Sulaiman bought the painting Face on the Land in 2003 for £40,000. In 2007, when Sotheby’s London auctioned Yue’s seminal 1995 work inspired by the Tiananmen Square massacre, Execution, it sold for a record-breaking £2.9mn – the highest price for a contemporary Chinese artwork at the time.

“People started to buy contemporary Chinese art in 1995,” explains Lam. “In the early 2000s – when Basma was there – it was just a very interesting, exciting time. There was this vibrant art scene, the government had not endorsed it, and there were only a handful of Chinese collectors – so tourists were going there to buy art as a souvenir, because the prices were low. After about 2006, though, it went crazy.” Before then, Al Sulaiman would travel to China regularly, discovering artists while visiting her daughter, who was working in Shanghai. But she met Lam for the first time at a dinner in London. The two clicked straight away – but more because of what they didn’t agree on than what they did, says Lam. “Basma loves political pop; I don’t. I consider political pop to be the western definition of Chinese contemporary art. And Basma likes figurative art; I don’t. But when you’re talking about art, it’s much better to have two different opinions,” she says.

The first piece Al Sulaiman bought from Lam was by Shao Fan – “a deconstructed Chinese chair, put together as a sculpture. And eventually, she bought Chinese abstracts,” says Lam, referencing two works in Al Sulaiman’s home by Beijing-based Zhu Jinshi, a pioneer of Chinese abstract painting who cakes his canvases in heavy, impasto layers. “He uses a shovel to throw on the paint,” says Al Sulaiman, standing in front of a large-scale triptych that she bought in 2015. “It’s so beautiful. When you think about it as a landscape, you can see it, you can feel it.”

In fact, abstraction is well represented in her home, and two minimalist, multi-frame works command the living space: the first, consisting of nine pink Plexiglas squares, is by French conceptualist Daniel Buren (Framed Colours, 9 Magenta Elements, 2007), and the other is a series of bi-colour paintings (Hommage à Le Corbusier, 2000) by German modernist Günther Förg. At the other end of the room is a huge work by Ghanaian artist El Anatsui, its undulating, nearly 5m-high form constructed from bottle tops pieced together with copper wire. “I bought it in 2012, but only when I moved in here in May was I able to see it,” she says. “It’s one of the reasons I bought this place: I needed big walls.” The art is all displayed, slightly incongruously, alongside 18th-century antique furniture – from France, Italy and England – and French Aubusson tapestries. “Pearl doesn’t like my carpets,” Al Sulaiman smiles.

The other place where Al Sulaiman’s collection lives is online. In 2011, she launched Basmoca, a virtual museum that can be walked around via an avatar. “I wanted eagerly to share the collection but the concept of building a physical space back home in Saudi Arabia was a bit difficult at that time,” she recalls. Instead, she explored the idea of creating a space within the online multimedia platform Second Life, but eventually built her own virtual world.

“Basically, Basma was doing metaverse before anyone else was doing metaverse,” says Lam. “But it was like gibberish to people,” adds Al Sulaiman. “Nobody understood it at that time, it was way too early. Now, of course, everybody is doing it.” Earlier this year, she showed a portion of her Saudi art collection in a physical space – inside Maraya, a striking, mirrored building in Saudi Arabia’s historic desert canyon site AlUla.

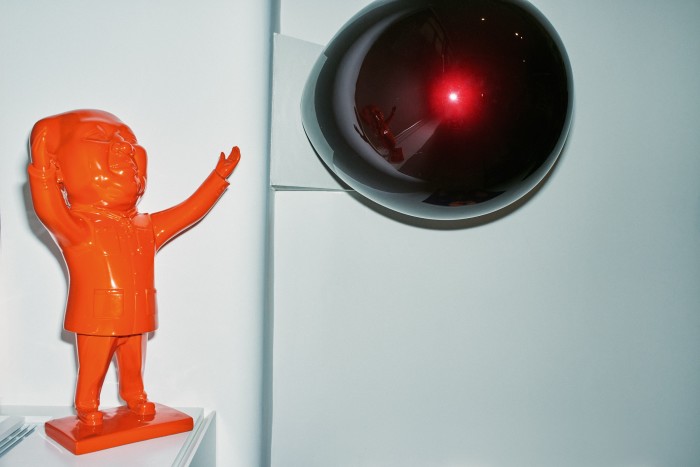

Al Sulaiman has also dipped her toe in NFTs. She points to a screen on the wall. “It resembles Monet’s Water Lilies,” she says of the digital work by Italian artist Davide Quayola, which plays on a loop and is surrounded by a wall of portraits – most are “classical”, but there is one with a cat’s head. “It’s supposed to be Mao,” she says of the painting by Shanghai-born artist Qiu Jie.

“It’s unusual for traditional art collectors to buy NFTs because they have no museum credentials,” suggests Lam, adding the cryptocurrency crash earlier this year has led to a weaker market for NFTs, but that they still have a role to play for a younger generation of artists and collectors. “There are young artists selling NFTs for $50 or $100. This is democratised art. And if it’s not NFT, another mode of technology will emerge.”

One of the artists Lam represents is London-based Philip Colbert, a self-titled “pioneer of the metaverse” who this year launched NFT project The Lobstars. And an artist Lam is keen to introduce to Al Sulaiman is Mr Doodle, aka British artist Sam Cox, who recently covered his entire Kent home in his graphic, graffiti-like imagery; the stop-motion video of the process has been watched nearly 2mn times on YouTube. “I did check him out after you told me,” says Al Sulaiman to her friend. “It’s very different. Interesting…”

“I know some of these things are not your aesthetic,” says Lam, “but I think it’s interesting because this is the new generation of artists. Our minds should be very open – my gallery mission is about cultural exchange.”

Both women describe each other as “open-minded”, and they often travel together, visiting art fairs and discovering new artists. A few years ago they went to Japan – to Tokyo and the island of Naoshima – with friends. Earlier this year they took a trip to Saudi Arabia – a first for Lam. They’ve also recently uncovered an artist they’re equally passionate about: Maha Malluh. “Her work is all about found objects, about reminiscing and history,” says Al Sulaiman, walking over to a sculpture constructed from old enamelled cooking pots. Another artist they agree on is Babajide Olatunji, who they came across at the Art Dubai fair, and whose work Lam bought on the spot – a charcoal and pastel portrait that is hyperrealistic yet depicts an imagined sitter. Lam will showcase the Nigerian artist at her Shanghai space next year, while another of his drawings has made it on to Al Sulaiman’s walls (via Sotheby’s, for £10,000).

Other works in Al Sulaiman’s collection include figurative paintings by Egyptian artist Adel El Siwi (Hamdi & Hamada, 2009) and Norfolk-based Jonathan Wateridge. But just as Lam considers herself a conduit for a diverse cross-section of artists in China, Al Sulaiman’s ultimate dream is to bring her eclectic collection to a permanent space in Saudi Arabia, where in 2014 she became the first woman to receive an award from the government for her contributions to the country’s art and cultural spheres. “Culture is a bond,” she concludes. “It bonds people in a special language that doesn’t need a translation.”

Comments