Li Galli: ‘The most magical place in the Mediterranean’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

From the many terraces that protrude from the pastel-hued vertical heights of Positano on Italy’s Amalfi Coast, it’s possible to make out a dark, rocky outcropping emerging from the Gulf of Salerno. Many travellers will be too engaged with their spaghetti alle vongole to notice it. Those who pass in a boat can see that it’s a trio of small islands, one of them marked by an medieval stone tower and two villas. Only a few, however, know Li Galli, and how mythical this tiny archipelago is.

“Li Galli must be the most magical place in the Mediterranean,” said the London-based gallerist Leopold Thun, son of architect Matteo Thun, who first visited the private island in his teens. “In ancient times, these were the Sirenuse, the islands of the sirens,” wrote the Cypriot artist Christodoulos Panayiotou. “This is where the sirens were said to use their enchanted voices to lure mariners into certain death.” Panayiotou, known for his research-based conceptual work, has spent weeks on Li Galli as a guest of its current owners, the art patron Nicoletta Fiorucci and her husband, hotelier Giovanni Russo.

The sirens of Homer’s epic poem haven’t been the islands’ only illustrious residents. In the last years of the Roman Empire an elegant villa stood on Gallo Lungo, apparently a favourite destination of Tiberius. Following the fall of Rome, Li Galli became a hideout for privateers. At the end of the Middle Ages, to protect the coastline from Saracen pirates, a series of stone watchtowers was built from Vietri sul Mare to Positano, including one on Gallo Lungo.

It wasn’t until Italian unification in 1861, when the coastal towers were officially redundant, that Li Galli was sold into private hands. In the 1920s, after spotting the islands from Positano, the famed Russian choreographer and dancer Léonide Massine fell for and purchased them, and began what would become a 50-year-long obsession with transforming Gallo Lungo – then a 14-acre rock with the remains of the watchtower, a cistern and an ancient landing place – into the extraordinary property it is today. Locals referred to him as the “crazy Russian who had bought a rocky island where only rabbits could live”, but Massine proved them all wrong, eventually even starting a dance school on the island. In his book The Siren Isles, the Italian author-academic Romolo Ercolino posited that the villas on the largest of the three islands, Gallo Lungo, built in the 1930s, were conceived by Le Corbusier.

“I think about Massine every day,” says Giovanni Russo, seated on a terrace at a massive marble table custom-designed for the site by the Cypriot-born, London-based designer Michael Anastassiades. Behind him is the porticoed veranda of the top floor of the main villa (the lower two floors disappear down the side of the island); in front of us, a mesmerising view of the other two islets and the glistening sea. “Without Massine this island would not exist as it does now. He spent all his fortune and energy on it. He rebuilt the watchtower and constructed the walkways and villas.” Russo points to the pine trees that cling to the rocky slopes. “He had all the trees planted, and had hundreds of metres of terracing created for gardens and grapevines.”

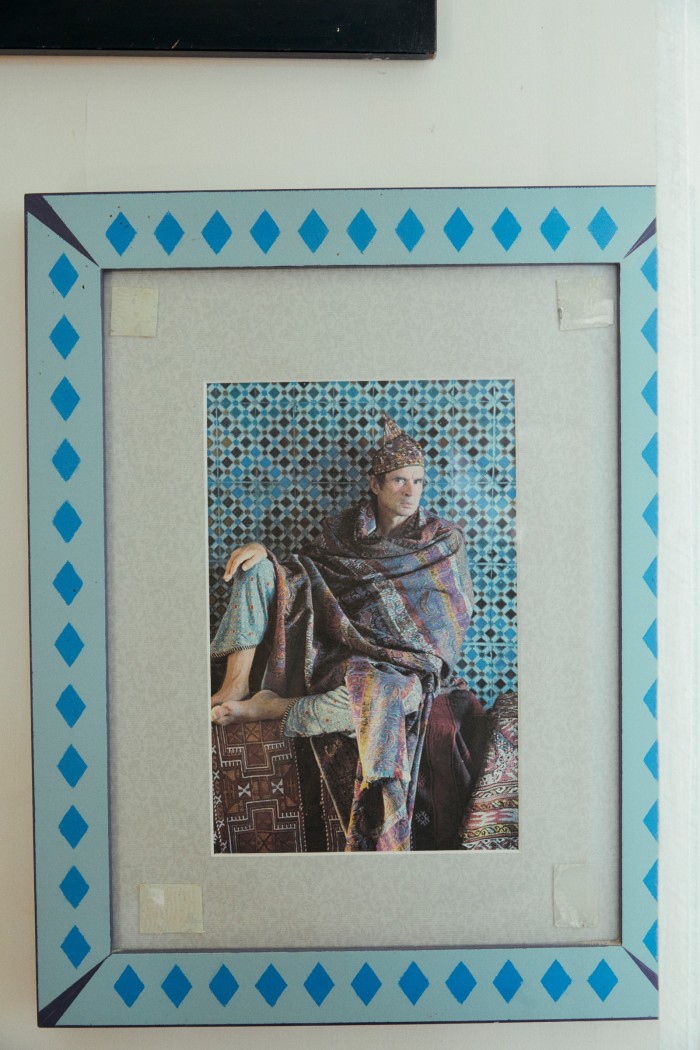

Russo himself acquired Li Galli almost 30 years ago from the Rudolf Nureyev Foundation; the legendary dancer had bought Li Galli in the late 1980s, just a few years after being diagnosed with HIV. In images from the period, Nureyev is sometimes portrayed posing naked on the island’s rocks, contemplating the sea. A collector of Anatolian kilims, he was said to have lined its paths and terraces with rugs. His primary contribution to Li Galli – one that endures and dazzles to this day – was to clad the central villa in Islamic-style patterned tiles imported from Istanbul; one room, which he used as a dining room, was barrel-vaulted and tiled on every surface, resembling the inner sanctum of a mosque. It’s also rumoured that he had a massive bathtub helicoptered in from Paris.

By the time Russo – who grew up in nearby Sorrento, the son of hospitality professionals – purchased Li Galli, Gallo Lungo’s buildings had fallen into some disrepair. His first task was to restore the tower and both villas; then the walkways that weave across the island, connecting them to each other as well as to the landing and terraced gardens.

“This island is like a big boat,” he says. “It requires constant maintenance.” Although he transformed a water tank into a small chapel dedicated to San Giovanni (they desalinate sea water for the island’s supply), Russo’s primary contribution to the island has been restorations of the buildings’ interiors, which include two public floors and two guest bedrooms in the tower, two bedrooms and several lounges in the main villa, and the master bedroom.

Initially, Russo sought the input of his cousin Marco DeLuca, one of the owners of the stunning boutique hotel La Minervetta in Sorrento. A mustard-yellow La Cornue kitchen was installed on the ground floor of the watchtower; in its main living room – used as a ballroom in Massine’s time – Russo framed the fireplace with repurposed majolica tiles and hung over it an ornate gilded mirror. Today, a section of a wall is covered with drawings and photographs by artists who have visited Li Galli, among them Julian Schnabel and Mimmo Paladino. A guest room in the tower – painted white, with sunflower-yellow furniture, a lacquered table with an image of the sun, and shelves filled with antique Buddhist offering vessels – is dedicated to Russo’s friend, the photographer Pat Fok.

Giovanni and Nicoletta met in 2003, when she was a guest at a party he threw on the island. “She arrived here swimming, like a mermaid” – having jumped off her boat, he recalls, smiling at the memory. Shortly afterwards (they didn’t officially marry until 2018), Nicoletta started planting both botanical species – exchanging the roses in the gardens for white oleander and blue plumbago – and ideas; together the pair continued to add more art to Gallo Lungo. Their master bedroom is defined by a towering white-and-turquoise Ettore Sottsass totem and an abstract fresco by Emil Michael Klein (Nicoletta commissioned him to paint directly onto the ceiling); in the bathroom, two colourful mosaic works by the Italian designer Cinzia Ruggeri hang on the walls.

Today, she invites artists and designers to come to stay on the island and make site-specific works; her vision for it is of a place for artists to meet, be inspired and disconnect from the world. In one of the main sitting rooms, a reflective gold triptych by Panayiotou complements the Islamic-patterned tiles; another, also covered in Nureyev’s tiles, features a joyful portrait of Fiorucci and Russo by the painter Patrizio Di Massimo. Most recently, she invited the Greek designer Savvas Laz to reinvent Li Galli’s boat house with furniture and mirrors produced with his signature technique of found Styrofoam covered in layers of Plexiglas.

Fiorucci began collecting with a focus on Old Masters; when her focus shifted to contemporary art in her 50s, she started actively to engage with artists she collected. In 2010, after buying Marina Abramović’s Casa Monte on the island of Stromboli, she, along with the Italian curator Milovan Farronato, informally founded the Volcano Extravaganza, an avant-garde festival described as a series of “wild” and ephemeral thematic interventions, which ended in 2019. Last year, in conversation with the gallerist Thun, Fiorucci began a new site-specific artistic project called Traces: artists are invited to spend several weeks on Gallo Lungo to think, work and disconnect. They are required to leave only a trace behind – “the last thing I want is a sculpture garden”, she says. Instead it’s all about “being close to the artistic process, observing it, having conversations about ideas”.

For the few months a year that Fiorucci and Russo are based on Li Galli, there is a constant stream of visitors. One day in late May, Fiorucci sent a boat to Sorrento to pick up the Liberian-British artist Lina Iris Viktor, who had recently moved to the coast, along with the London-based artist and scientist Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, who was on holiday in Positano. After a lunch of Russo’s favourite gnocchi, Viktor, Ginsberg and her husband chatted by the saltwater infinity pool, built into the rocks of the main terrace. Later, Fiorucci led Ginsberg to the other end of the island, an area covered in native wildflowers, to meet the island’s beekeeper. They discussed the possibility of creating a work along the lines of Ginsberg’s Pollinator Pathmaker – an 745ft-long flowerbed planted at the Serpentine last summer, supported by Fiorucci’s not-for-profit Art Trust – at Li Galli.

Even today, it’s nature that calls the shots in this remarkable place. The Italian artist Giangiacomo Rossetti, who had been invited to the island for three weeks to take part in the Traces project, was delayed more than a week by storms. “I was trapped in a kind of limbo,” he says, “just waiting, and getting nervous about the idea of being removed from the world. And then, once I finally arrived, all the anxiety lifted. I could stay here for months.” It’s late afternoon, and he is seated at a small table beneath a pine tree on one of the tower’s terraces. Out of nowhere, a sudden wind kicks up; a haunting sound – half whistle, half howl – fills the air for at least a minute. Rossetti looks simultaneously startled and thrilled. “Finally!” he laughs. “I have heard the song of the sirens.”

Comments