From porcelain bricks to bamboo baskets, Asian Art in London is a celebration

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

As part of this year’s Asian Art in London summer showcase, gallery Priestley & Ferraro will unveil the work of the first academically trained Chinese painters to settle and work as artists in the UK. Theirs is a lesser-known story, compared to the more often chronicled 20th-century Chinese artists in Paris.

Mist and Clarity opens a hidden window on to a particular moment in time and on to two artists, the multitalented Chang Chien-ying (1909-2003) and her husband, artist and academic, Fei Cheng-wu (1911-2000). The pair not only came to meld the artistic sensibilities of east and west but also contributed to the wider understanding of Chinese culture in postwar Britain.

Their mentor, the progressive Xu Beihong, firmly believed that Chinese artists could learn from western traditions, particularly the close observation of nature, and selected both for grants to study in London in 1946. They appear to have been welcomed by the British art establishment and offered additional opportunities to study and exhibit. The couple married in 1953 — with their friend Stanley Spencer in attendance — and never returned to China, by then under communist control. A representative range of 46 smaller-scale watercolours and ink paintings are on offer, including Fei’s eloquent “White Iris” and Chang’s expressive “Old Tree” (prices from around £1,000).

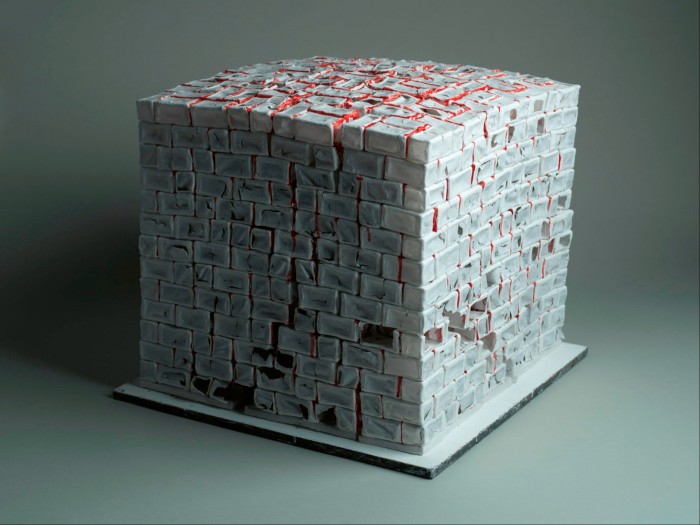

Eskenazi gallery’s first foray into conceptual art focuses on the precarious porcelain sculptures of Fang Lijun, the leading proponent of the Cynical Realist movement of the early 1990s. He was best known for his lurid, monumental paintings of baldheaded men who vent the disillusionment, rage and angst felt by a generation of young Chinese. Each of his ceramic stacks is a fragile carcass of hollow bricks. Little more than air and paper-thin, they were indeed made of paper, dipped in slip (clay and water) and glaze. In the intense heat of the kiln, this paper frame combusts and disappears, leaving the fired slip and glaze to support the structure — but only up to a point.

It is this tipping-point that interests the artist: the limits to which he can push his medium before total collapse or destruction as the pieces emerge from the kiln. He relishes this volatility and unpredictability and the very imperfections that Chinese potters spent millennia attempting to eradicate or rectify. His blocks crack, flake, break and threaten to implode, glazes drip and pool ($15,000-$70,000).

In Eskenazi’s second show, 31 works by 18 artists from Japan — two of them former National Living Treasures — reveal not only the virtuosity but also the ingenuity of Japanese craftsmen and artists working in bamboo. From a classical, Chinese-inspired flower basket made from old arrow shafts combined with gold leaf and red and black lacquer by Tanabe Chikuunsai I, the dexterous plaiting, knotting, twining and wrapping techniques of these pieces soar in imagination above and beyond the utilitarian. They become pure abstract sculpture.

Yufu Shōhaku takes bundled and freestyle plaiting to exuberant complexity while cool, mathematical geometries are explored by Shōno Tokuzō. Bamboo is formed to resemble a filigree nest or, by Sugiura Noriyoshi, evoke the sounds and rhythms of a whirlpool (all pieces $4,000-$32,000).

Like Asian Art in London’s larger autumn event, this June initiative, now in its second year, presents long-established and emerging dealers, mostly clustered around Bond Street and St James’s or Kensington High Street. Among the new blood is the Beijing-trained Shanshan Wang, a self-styled one-woman band whose gallery in St James’s presents a show of her speciality, Korean ceramics. Opening with the distinctive, gentle Goryeo celadon porcelains of the 12th-14th centuries, it ends with the contemporary Korean ceramicist Shin Sang-Ho, renowned for his interpretation of traditional forms and techniques (£2,500-£15,000).

While several dealers take the opportunity to showcase more affordable modern or contemporary works and meet new clients, there are plenty of traditional rarities too, such as Chinese export porcelains at Marchant Asian Art and Jorge Welsh gallery. Presiding over the latter’s show is an exceptionally large pair of Kangxi period (1662-1722) triple gourd-shaped vases, striking not only for their scale but also their gleaming mirror-black glaze combined with famille verte enamels and gold (£10,000 to high six-figure sums). Lam & Co flourishes Imperial China in Miniature: A Collection of Ten Exquisite Artifacts, featuring the ceramics and other treasures which are their speciality.

The Asian Art in London showcase at Gallery 10, Cromwell Place, suggests the rich diversity of the city’s trade. Chinese textiles come courtesy of Jacqueline Simcox — not least a beguiling late-Ming-dynasty blue silk brocade panel woven with rows of fantastical winged leopard-like creatures surrounded by flying magpies and catfish (£18,000). Here are Japanese woodblock prints (Anastasia von Seibold), Indian arms and armour (Runjeet Singh) and contemporary Indian tribal and folk art (Anrad Gallery).

Asian Art in London is a good time to visit these exhibitions, but the galleries are open year-round, so there’s always something to see if your appetite has been whetted.

June 28-July 1, asianartinlondon.com

Comments