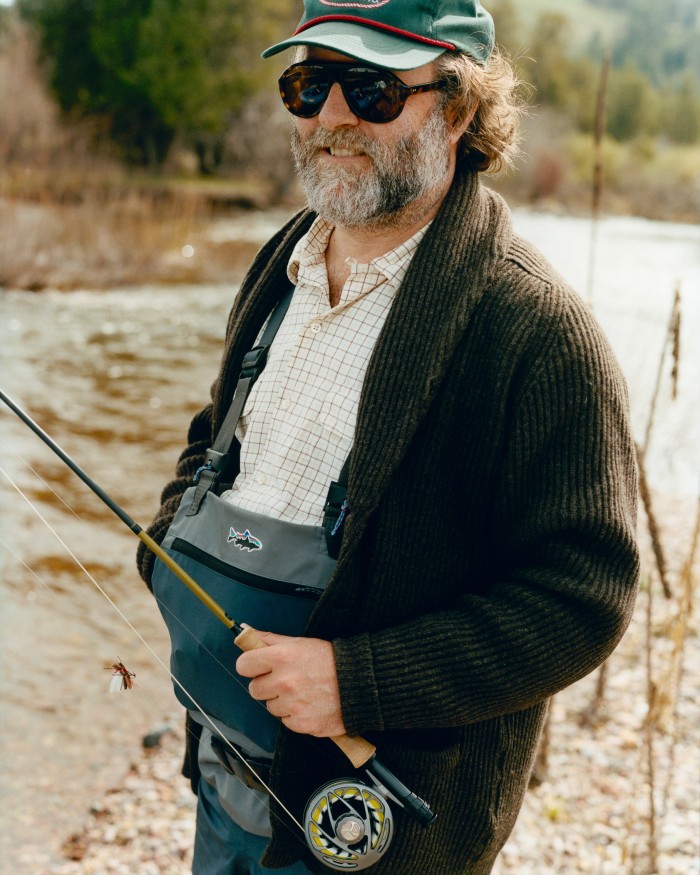

Two friends, one angling fantasy in Montana

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Montana is home to the American fly-fishing imagination. I feel a shiver of excitement when I think about the legendary rivers: the Madison, the Big Hole, the Gallatin, the Yellowstone. There are more, too many to name – most renowned, a few still secret – that flow through the plains or snake through the alpine slopes. These rivers are etched in the hearts of anglers everywhere.

I started visiting in my 20s, a few decades ago now. I drove out from our cabin in Wisconsin. It felt correct to drive; it gave me time to conjure visions of rising trout as I sped across North Dakota and the Badlands, into Big Sky country. I listened to Tom Petty as I climbed rolling golden hills and pine-covered mountains while trains ran in the distance. When I reached Montana, I fell in love: with the landscape, the sense of openness, the trout, the dive bars.

I know I’ve arrived when I start to see the brown-and-white, ’50s-style fishing access signs, indicating landings where you can put in your boat or wade into rivers; places that are landmarks themselves. The names make the angler’s heart race: Point of Rocks, Mallard’s Rest, Three Dollar Bridge. Sometimes I pull over just to watch the water moving by. There are further signs of the angling life: guides’ trucks hauling drift boats, and people clearly in town to fish. And fly shops everywhere: Melrose, a town with about 200 people, has more than Manhattan. The pilgrims make their way, and you know you’re in the right place.

There’s nothing efficient about fly fishing. If all you want to do is to catch a fish, there are easier ways to do it. You wouldn’t ask a person why they drive a vintage Jaguar when the latest model has cruise control. You want a connection to history. Fly fishing is continuous, in a way that would be recognisable to anglers from 100 years ago. Our rods are no longer bamboo (except for the real aficionados) but the principles remain unchanged.

The most poetic way to catch a fish is on a dry fly. This fly drifts along the surface of the water, where a trout, in the platonic ideal of the sport, takes it in plain sight of the angler. You retrieve line as the fish tires – this takes a few minutes – but finally, sitting next to you on the bank, is a brown trout. Your separate worlds are now united. You admire its golden body, the black spots lined with red, then you return it to the water. No two brown trout are the same, but each one is perfect.

It’s really as simple as that. Oh, wait; not at all. Things rarely go to plan. Fly fishing depends on conditions. Conditions were tough out there, we sigh. You can’t argue with the weather. This is easier than considering the possibility of user error. Bad casts, creaky reflexes, flies caught on trees that seem to have just grown behind you. Your line gets knotted and tangled, you might hook your own hat. Good grief. You might ask yourself, ‘Why am I doing this?’ And still you return.

I think of fishing in Montana as more than just being on the water. It’s the entire trip, all the anticipation as you head out into the elements. The weather arrives without warning – sun and storm, heat and cold. Icy rivers and fields that turn green in spring, and then yellow in the heat of summer. Rocky peaks covered in pine trees standing rigidly to attention.

You might begin at The Western Café in Bozeman, America’s best restaurant that closes at 2pm. You drive into Yellowstone National Park, one of the nation’s great legacies, down into the Lamar Valley, and then fish on the winding Soda Butte Creek while bison graze in the distance. The drift of your fly has to match the speed of the current, so throw your line upstream – called a mend – to make sure everything aligns. The fish are feeding, but a fly that drifts at the wrong speed will be rejected with extreme prejudice.

If you’re lucky, you catch a cut-throat trout – golden brown, with a rose slash near its jaw that inspired its name. Looking up at the mountains, you feel like you’ve made some good decisions in your life. Afterward, in the Old Saloon in the town of Emigrant, you toast your glory, and conveniently ignore the lesser lights of the day.

On a recent trip, my friend James and I headed toward Missoula, the area where Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It was set. My grandfather knew the great author, when they both taught at the University of Chicago; I like to think of them as friends, although their relationship was more professional. Missoula has the appeal of a college town in the mountains: everything invites you outside. Like most Montana cities, it’s incongruous – the centre is small while the surroundings are immense. It’s intimate, on a grand scale. If you live near the Blackfoot, as the book’s characters do, you can head out any time the fish are rising. If you live in New York, as I do, you plan your trip in advance, and pray the weather gods smile down on you.

Not this time. The unseasonable warmth melted the mountain snow early, and the run-off meant the rivers were high, brown – almost angry. There would be no fishing on the Blackfoot. Conditions were tough. Plan B was the Clearwater, a smaller river that flows through many lakes, so is cleaner. Though the water was still high, we had a better chance in the slower sections, which is where I got one good brown trout that jumped twice before we netted him.

Next stop was Rock Creek; that was high too. Though we were wise to stay at The Ranch at Rock Creek. This is not the sort of place I checked into as a 20-year-old, when I was dirtbagging across the state. Here you eat morels by the fire in a great timbered dining room and consider a deep wine list. You stay in a tasteful wooden cabin with a stone fireplace and a welcoming porch. You can imagine settling in for a week or a month, or maybe even making a life change and just moving right in. On Rock Creek, we floated beneath lovely red cliffs and an eagle’s nest the size of a piano. I caught a cut-throat, which looked even more golden pink on a grey day. A slow day of fly fishing makes a philosopher out of you. During these down moments, anglers have devised some rather dreadful clichés. That’s why they call it fishing and not catching. After another strike-out: a bad day of fishing is better than a good day at work. Like all clichés, there’s some truth in them. When you’re on the water, day after day, you do feel connected to a better way of living. You’re out of reception, away from the news cycle. Regardless of the fishing, I’ve never had a bad day in Montana.

On the last day of the trip, after all the high rivers, I still felt I had some unfinished angling business. I drove down to Paradise Valley, south of Livingston. Here, the spring creeks would be familiar to those who fish in England. The water is always clear, the fish visible and wary. I’ve fished here quite a few times over the years. The creek runs through the valley, which is very flat and warm in the sun. Mountains, covered in snow, rise all around you and provide a sense of scale. This is an immense space, you but a small part of it.

Fishing, when you’ve done it long enough, forms a continuum. You think of the people you’ve been on the water with, the places you’ve fished, the triumphs and the heartbreaks. I remember exactly where I lost an enormous fish in DePuy Spring Creek, not far from here. It went downstream and never came back. That was more than 10 years ago. The rod vibrated with a charge in my arm I’d never felt before. Then it went slack. Nothing. Storm clouds rolled through, low in the sky. I assured myself I’d get over it, and am still telling myself that.

Today, I pull up at Armstrong Spring Creek in the afternoon. I leave my rod fee in a coffee can in the farmhouse. This is a working ranch, and everywhere are black Angus cows and their newborn calves. A fishing trip makes anglers susceptible to the power of narratives; a dangerous business. The finite nature of our week in Montana – no matter how many times we’ve been before – intensifies everything. The prospect of late success weighs on me.

The fish begin to rise, little breaks in the water that look like a stone dropped through the surface. In this situation you use finer tippet, the delicate material that looks like a strand of a spider’s web that’s tied to the fly. That means the fish won’t see it; it also means I can’t be aggressive should I catch one. I’m casting a blue-winged olive, a size 24, a little wisp of grey with a green body; about the smallest fly there is, the size of a crumb of bread. I drift this over a few fish. No luck. I move up to a good riffle and cast to the seam where the fast and slow water meet. There’s a disturbance and I raise the rod: a fish. Until I feel the weight on the line I don’t know if it’s a good set. This brief moment, no more than a half-second, is excruciating. But then there’s the weight; the trout is on. It quickly moves to the deeper water. I back up onto the bank and ease it toward me. I don’t have a net, for a variety of reasons, but after a time I bring the trout into the shallows. A rainbow trout, golden, streaked with a deep-pink stripe, the entire body covered in fine black spots, like a thousand drops of ink. I unhook it in the water. No photos. The trout swims quickly into the pool and out of sight.

Nothing has changed. The cows are still in the fields, the snow is still on the mountains, the trout are still in the stream. But I feel renewed. This is an old sport, and I feel lucky it exists in our time.

David Coggins and James Harvey-Kelly stayed as guests of The Ranch at Rock Creek, from $2,000 per night for two

Comments