Artist Zadie Xa: ‘I’m drawn to wayward creatures’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A mythological grandmother riding a fantastical lion is the opening sculpture in Zadie Xa’s immersive installation, “Nine-Tailed Tall Tales: Trickster, Mongrel, Beast”. It is flanked by two brilliantly coloured abstract linen patchworks suspended from the ceiling. One alludes to Korea’s seven rising moons; the other to the seven setting suns of Canada’s Pacific north-west, the artist’s birthplace.

The new installation at Space K in Seoul is Xa’s first solo show in South Korea, the land her parents left for Vancouver in the late 1970s. “I love linen’s translucent effect; it’s like stained glass,” she says, conceiving the hangings, whose dual inspirations are traditional Korean quilting, or bojagi, and American Modernist colourfield painting, as “portals or windows, but also veils”. (Thaddaeus Ropac gallery is showing her work “Reciprocal Relations” (2021), with hand-sewn denim and oil on linen, at Frieze Seoul.) Progressing from this portal to a maze then an expansive shrine, the work, Xa says, uses “principles of collage, assemblage and layering” that chime with the “way I thought about my upbringing: the hybrid and diaspora pieces of information that made up who I was”.

Xa, 39, now lives in east London, working between two studios to accommodate the range of her collaborative practice, from painting and textiles to sound and performance. Displaced as a pre-teen from inner-city Vancouver to a mostly-white suburb, she found herself “in a space you don’t feel you fit in” — a malaise that persisted through painting studies in Vancouver and at the Royal College of Art in London. “References within British painting didn’t resonate with me . . . Slowly I started looking inwards.”

She turned to ancestral crafts and performance, together with ideas of “protest, community and women’s work”. Bojagi embodies matrilineal knowledge passed down through sewing rather than writing, and she senses kinship elsewhere, such as with the Gee’s Bend quilters of Alabama: “Geometric genius doesn’t always come from the spaces we assume.”

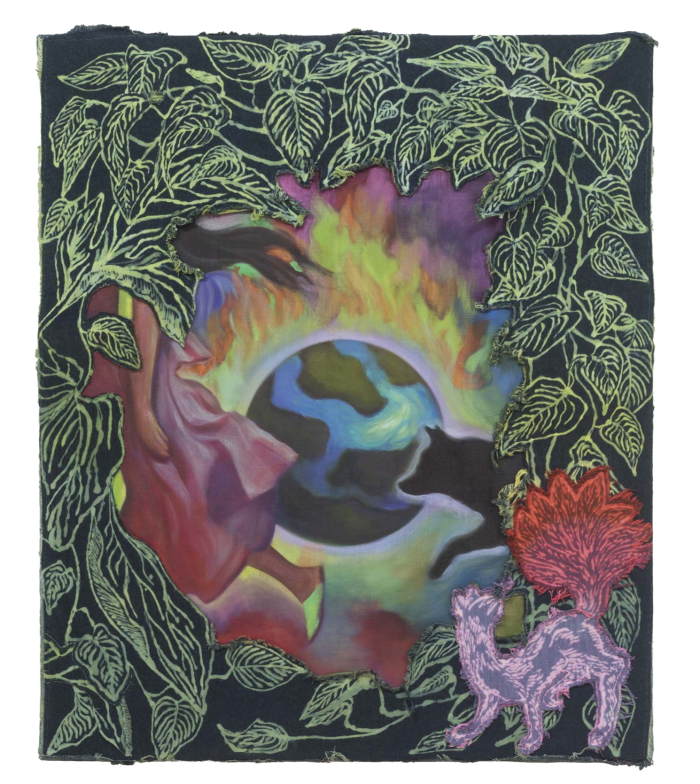

When she recently returned to painting, sometimes framing figurative oils with bojagi patchwork, it was with a narrative edge unfashionable during her student days. Her focus is on “picture-making, theatrical backdrops and storytelling”, with an abiding interest in “animals as stand-ins for human behaviour; through folklore and children’s tales we can critique human society and morals.”

“Nine-Tailed Tall Tales” groups 23 new works with others seen in “House Gods, Animal Guides and Five Ways 2 Forgiveness” at London’s Whitechapel gallery in 2022. “Sisters” (2023), an oil painting of two long-haired older women styled as a seagull and a fox, develops characters from her collaborative performance “Scorpion” (2021) at London’s National Gallery, in which two dancers, in red and white, interacted with paintings arranged in a 3D structure.

Xa is drawn to “wayward creatures” such as the legendary “nine-tailed fox spirit that transforms into a beautiful woman to lure (usually) men” and devour their innards, to “regenerate itself and become human”. The fox and coyote are seen in folklore as “dangerous, violent animals that live on the margins of society and use cunning for survival”. In these wily outcasts who move between worlds, she finds a metaphor for all those obliged to adapt and survive through charm and subterfuge.

Putative hags and witches are reclaimed as archetypal heroines. In the opening space, in which Grandmother Mago rides a haetae — half-lion, half-goat — modelled on the artist’s Pekingese dog, Xa reimagines an “east Asian deity who created the Earth with her excrement and urine”. Whereas “creation myths, especially in Korea, generally start with a man”, her goddess is a “vulgar, visceral image of a powerful elderly woman who works with her hands”.

The maze structure, or meditative labyrinth, reflects the tapestries’ geometric patterning when seen from a viewpoint upstairs. Jewel-like carpets mirror the colours and geometry of the walls. “I think of it as a diasporic journey,” Xa says, “but I wanted it more playful and loose.” Perched on the maze walls are small, hand-painted sculptures inspired by Korean kkokdu, wooden funerary figures that guide the dead in the afterlife. They were made by her husband and artistic collaborator, Benito Mayor Vallejo, modelled virtually and 3D-printed in corn-based photo-polymer resin.

In the final shrine-like space is “Princess Bari” (2022), Xa’s take on a shamanistic robe — homage to an often female-led practice, based on oral knowledge, that was suppressed in Korea. The hanbok’s stylised cabbage leaves allude to kimchi, the pickle now vaunted as a superfood, while knives made of reflective fake leather suggest both ritual blades and women’s kitchen tools.

For Xa, performance, ritual and theatricality are ways to preserve history. “I’m inspired by people of any culture who carry on traditions,” she says. “As a diasporic person, you have access to the culture of your ancestors through spirits and ghosts.”

To October 12, spacek.co.kr

Comments