Rabat plots route past earthquake shock and tougher economic straits

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Soon after an earthquake struck Morocco on September 8, killing some 3,000 people, the country’s ruler, King Mohammed VI, announced a five-year Dh120bn ($11.7bn) reconstruction package to rebuild villages and support those who lost homes and livelihoods.

The plan would aim to help 4.2mn people in the worst affected areas, according to Moroccan officials. The High Atlas mountains — epicentre of the 6.8 magnitude quake — are in one of the poorest regions of the kingdom. There, about 60,000 houses in 2,930 villages have been damaged. A third of the houses have collapsed, officials say.

But in spite of the tragic loss of life, and the destruction, analysts do not expect a massive impact on the country’s diversified economy. While there may be some short-term effects on agriculture and tourism in the region, key sectors such as financial services, the automotive industry, and fertiliser production are based far from the stricken area.

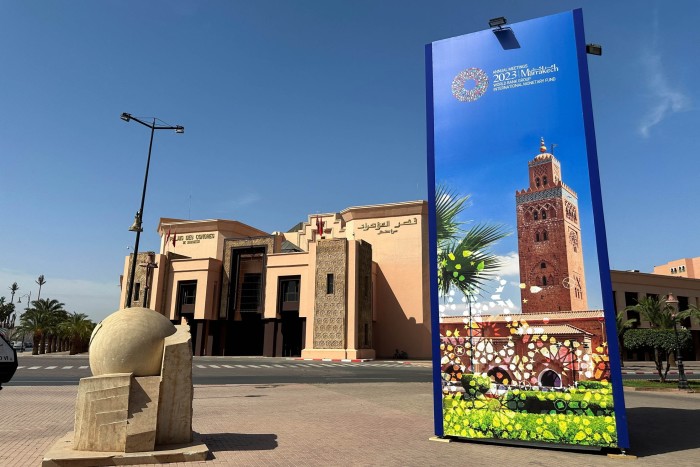

And, although they are closer to the epicentre, the annual meetings of World Bank and IMF in Marrakech on October 9-15 will go ahead.

“The impact should not be too bad on the economy in the short term,” says James Swanston, analyst at Capital Economics, the London-based consultancy. “As for the reconstruction plan, it is spread over the course of a few years and shouldn’t raise any concerns with Morocco’s financial position.”

Before the September earthquake, gross domestic product was expected to grow in 2023 by 2.9 per cent.

In late September, Abdellatif Jouahri, governor of Bank al-Maghrib, the central bank, said it was too early to assess the earthquake’s impact on growth, debt and the budget, suggesting the picture would become more apparent at the end of the year.

He added that Morocco has “specific financing lines set aside for similar circumstances” and that the country had a $5bn flexible credit line from the IMF at its disposal. “We will be able to use this line without conditionality since we are facing a shock,” he explained.

The IMF credit facility was agreed upon in April. At the time, the lender described Morocco as having “very strong fundamentals and institutional policy frameworks, [and a] sustained record of implementing very strong policies”.

It said the facility was aimed at addressing “elevated” risks to the economic outlook, mainly recurrent droughts that damage growth and impact the large section of the labour force — 39 per cent — that is engaged in agriculture.

Another risk, said the lender, was inflationary pressures from elevated commodity prices as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The Moroccan economy had rebounded strongly from the Covid pandemic, growing by 7.9 per cent in 2021. But, in 2022, a combination of severe drought and higher global food and energy prices caused growth to plummet to 1.1 per cent while inflation rose to 7.6 per cent.

“Food imports increase in periods of drought, but we have to tolerate it,” Jouahri said in September. “No doubt it is one of the risks of the coming period, but there are solutions.” He explained that food accounts for 39 per cent of the spending of Moroccan families and that 20 per cent of it is imported.

Morocco has now suffered five consecutive years of drought, leading to increased wheat imports and a bigger outlay on flour subsidies. Some 175,000 jobs were lost in rural areas in 2022 because of the poor rains, according to the World Bank.

As a result, there have been periodic protests against the high cost of living in Moroccan cities over the past two years. Although mostly small, analysts say they underline the risks posed by rising prices.

Jouahri noted that Morocco had very low inflation for three decades before the pandemic, but that changed after Covid. The central bank increased interest rates three times, most recently in March 2023. Inflation peaked in February at 10.1 per cent and was down to 5 per cent in August.

“Our economy is resilient because it is highly diversified,” argues Lahcen Haddad, an economic consultant, former minister and member of the Moroccan senate. “Morocco has also adopted a countercyclical approach> So, during the global financial crisis in 2008-09, it invested heavily in infrastructure. After Covid, the government has been spending on social security coverage and on water and energy projects.”

The kingdom has the biggest automotive sector in Africa, with exports, mainly to Europe, in the first eight months of 2023 rising 36 per cent to $8.7bn. Renault and Stellantis are the main investors in the industry, and have benefited from the kingdom’s proximity to Europe and its low relative labour costs. Morocco is also one of the world’s top exporters of fertilisers, with exports of $4bn until the end of July.

Europe remains Morocco’s main trading partner, with France and Spain in the lead, even if political differences sometimes strain relations. Morocco is alleged by Belgian and Italian investigators to have bribed Pier Antonio Panzeri, a member of the European parliament, to influence votes in its favour in the assembly. The kingdom has denied the allegations; Panzeri awaits trial and has promised to co-operate with the Belgian authorities.

While the allegations have strained relations with the European parliament, analysts say that many European countries and the European Commission would prefer to brush the scandal away. Morocco plays a vital role in limiting migration to Europe and is also considered an important economic partner.

“The Europeans are betting on Morocco to be a reliable source of green hydrogen and renewable energy,” points out Riccardo Fabiani, north Africa director at the International Crisis Group, an independent non-governmental organisation. “It is part of Europe’s long-term strategy to decrease dependence on fossil fuel, Russian gas, and reduce carbon emissions. Morocco is seen as a stable exception in a turbulent region.”

Comments