From Brooklyn to Albany, the Hudson eyes a commercial revival

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In June 1932, in the depths of the Great Depression, Franklin Roosevelt travelled to Albany, New York to inaugurate the city’s port — a ceremony that featured 5,000 parading soldiers, 25,000 cheering spectators and a symbolic “wedding of the waters”.

The then-governor — soon to be president — celebrated the docks along the Hudson River as a source of well-paying jobs at a time of economic despair and part of a larger project to open the nation’s inland waterways to commercial traffic.

Nearly 100 years later, the Port of Albany is in the middle of another transformation, hoping to reclaim a role as an engine of economic renewal for the wider region. The cause for excitement was its selection two-and-a-half years ago as the nation’s first site for manufacturing the soaring steel towers that are the spines of offshore wind turbines.

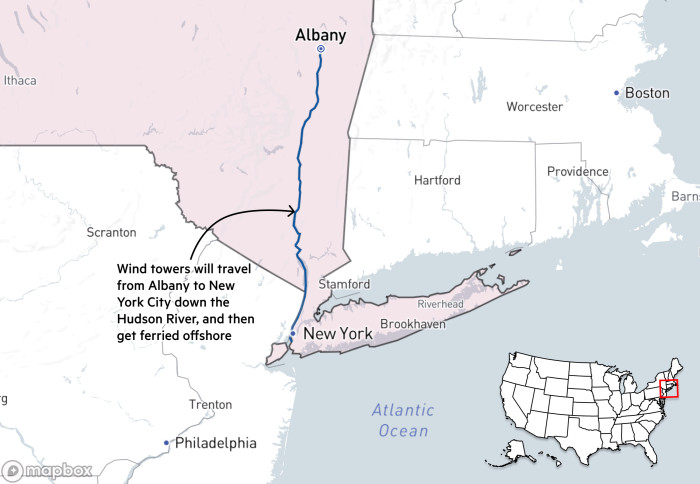

A subsequent contract calls for the port to churn out as many as 100 state of the art wind towers a year. These would then be loaded in sections on to barges and floated 120 nautical miles downriver to a staging ground at a refurbished South Brooklyn Marine Terminal in Sunset Park, New York City. From there they would be ferried offshore — by a plug-in hybrid ship — to wind farms being built by Norwegian energy group Equinor and its partner BP.

“It’s generational,” said Megan Daly, the Port of Albany’s chief commerce officer, as she explained the impact that offshore wind could have not only on her facility but the wider region. “This could be a job for the rest of [their] life,” Daly said of residents of Albany’s South End, an impoverished and polluted neighbourhood next to the port.

The enthusiasm has been tempered of late by bulging costs that have cast doubt over the project. In October, New York’s public services commission rejected a request by Equinor and its partners for billions of dollars in additional subsidies to account for rising inflation and scarce construction materials. The estimated cost of the Albany manufacturing plant had jumped from $357mn when the contract was signed to more than $600mn, according to Equinor.

Molly Morris, the president of Equinor Renewables Americas, expressed disappointment saying: “These projects must be financially sustainable to proceed.” On Friday, the company announced a $300mn writedown on the value of its US offshore wind portfolio.

While Equinor and others weigh their options — including walking away — New York officials insist they remain committed to building an offshore wind industry. In October, the state announced provisional contracts for a trio of offshore projects that would be its largest yet. The governor’s office also issued a 10-point “action plan” to address the cost challenges. Its suggestions include indexing contracts to inflation, helping companies access low-cost financing and moving to “backfill” contracts that are terminated.

“It’s fair to say we’re in a situation where there are market dynamics that have created headwinds for many projects . . . not only in New York, but writ large,” Doreen Harris, president of the New York Energy Research and Development Authority, told local media. The path towards the state’s ambitious clean energy goals, she acknowledged, “may not have a straight line”.

Despite the mounting uncertainties, offshore wind is stirring the promise of renewal at ageing ports and terminals along America’s eastern seaboard. As in Albany, European companies are centre stage. Having built a world-leading industry at home, they are now leading the development of what the administration of Joe Biden hopes will be an American equivalent. They have been encouraged by state and federal grants as well as tax incentives in the administration’s $369bn Inflation Reduction Act. Some of those projects are significantly further along than New York’s.

New Bedford, Massachusetts, a once-great whaling town that featured in Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, is trying to reinvent itself as an assembly point for offshore towers. They will be destined for the Vineyard Wind project, half-owned by Denmark’s Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners.

Just down the coast in New London, Connecticut, a German cargo ship arrived in August with a first shipment of Siemens-made turbine blades. It landed at a terminal that has been upgraded with $255mn in investments from the state and a joint venture between local utility Eversource and Denmark’s Ørsted. Together, they are developing the South Fork wind farm 35 miles east of Long Island.

In Portsmouth, Virginia, Siemens Gamesa has leased 80 acres — a quarter of the port — for a blade manufacturing facility that will serve a wind farm 27 miles off the coast of Virginia Beach.

Then there is the 73-acre South Brooklyn Marine Terminal site, currently used as an occasional overflow parking lot for the UN. It would be spruced up with $250mn in investments from Equinor and an equivalent amount from the state to serve as an assembly point for offshore turbines. It would also host a maintenance yard and the substation where power generated at one of Equinor’s offshore fields connects to the grid.

And, just 10 miles down the river from the Port of Albany, GE Vernova has proposed two factories at the privately owned Port of Coeymans. One would produce offshore blades and the other nacelles, the boxes that house turbines’ generating equipment. Meanwhile, a New York engineering company, Riggs Distler, has won an $86mn contract to build enormous foundations at Coeymans — some weighing as much as 120 tonnes — that will be used to anchor offshore turbines.

“There are jobs for people at every level,” said Kathy Sheehan, Albany’s mayor. “You don’t have to have a four-year degree.”

Albany is not the first place that comes to mind when one thinks of offshore wind. The state capital is more than 100 miles inland and is better known as a place where lobbyists come to do their bidding when the legislature is in session.

Its port is the last navigable stop on the Hudson for large ships before the way is blocked by bridges and then canals that lead into the industrial Midwest. The port handles everything from scrap metal bound for Turkey to incoming Australian molasses. Goods are stored in hulking silos, some dating from the Roosevelt era.

“This is a port of entry, so a ship can go from here right out to the world,” Daly said.

In 2014, the port had a banner year shifting GE generators produced in nearby Schenectady and bound for Africa. Like wind turbines, they are large and unwieldy objects that require specialised handling.

A few years later, the port’s board was searching for new growth just as the federal government began leasing sites off the north-east coast for possible wind farm development. Equinor won three lots off Long Island — known as Empire Wind 1, Empire Wind 2 and Beacon Wind 1. It then negotiated an agreement with New York state to supply power — some 3.3GW, or enough to power nearly 2mn homes.

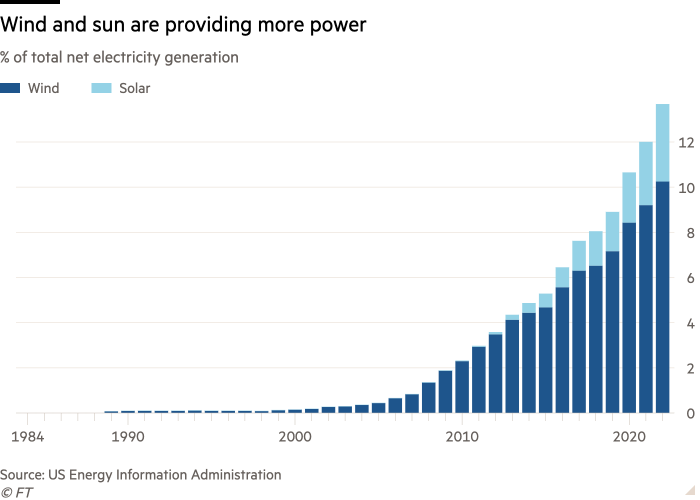

That contract is part of New York’s goal of generating 70 per cent of its electricity from renewable sources by 2030. The state has also set a target of installing 9GW of offshore wind capacity by 2035. It dovetails with the Biden administration’s own goal of US offshore wind capacity hitting 30GW by 2030.

But New York also wants offshore wind to bring economic development. The contract the state negotiated with Equinor, for example, mandated that the company help establish various links in the offshore wind supply chain — from factories to job training.

“We’re going to have the whole ecosystem, the supply chain, that’s been missing before,” said governor Kathy Hochul when she visited the port in January 2022 to announce a second tranche of offshore contracts, of which the wind tower factory was a part.

As Jennifer Granholm, US energy secretary, looked on, Hochul sketched out a vision of Bidenomics centred on 450ft, New York-made wind towers, floating down the river past Manhattan. “People are going to look at that . . . and say, ‘Wow! That’s the future heading down the Hudson River.’”

For now, the future is a vast, gravelly lot along the Hudson that was once covered in fly ash from a nearby power plant. It measures roughly 85 acres, large enough to host four factories totalling 600,000 sq ft. Those factories would be operated by Marmen Welcon, a joint venture of Canadian and Danish companies that specialise in offshore towers. Equinor would be their customer — although they could eventually supply other operators, too.

FT Live event: Investing in America Summit

7 November 2023

Can foreign multinationals continue to find opportunity in the US?

In-Person & Digital | Miami, PAMM | #FTInvestinginAmerica

Roddy Yagen, the head of construction at the Port of Albany, has been preparing the site in the hope that work can begin in earnest as soon as the cost dispute is resolved — assuming it is. (If Equinor opts to end its contract, one possibility is that it could be re-bid.) The port has already dealt with numerous rounds of permitting and environmental reviews, which required a plan to relocate sturgeon and protect underwater vegetation. It has also prevailed against a lawsuit filed by residents seeking to halt the project for further study of its impacts.

Richard Hendrick, the port’s chief executive, said that Albany was still committed to offshore wind, despite the dispute between the state and the developers. “Everyone understands that in real time, doing the same thing with less funding is incredibly difficult. However, the ultimate goal of creating renewable energy sources and a domestic supply chain to support that endeavour is worth the effort.”

On a recent afternoon, a dump truck rolled back and forth, smoothing ground that had been flattened and reinforced to sustain the enormous weight of the towers. Rusted train cars were parked to the side. A blue strip of river was visible in the distance.

Looking out over the site, Yagen explained how it would function: first, steel plates — many made in the US — would arrive by rail and then be rolled and welded in one facility before moving on for grinding and X-rays in another. Then comes special treatment to protect the towers from the ocean water, and then the ladders and platforms and other add-ons. When completed, the 450ft towers would be moved in three 150ft sections to a newly expanded wharf where cranes would then load them on to barges for the trip to Brooklyn and then the open sea.

“As with any new industry, it’s going to cost more than maybe what we initially had targeted pre-pandemic,” said Albany mayor Sheehan. She pleaded for the state and the energy companies to hold fast: “If we delay, it’s only going to be more expensive for us down the road.”

Comments