Cleveland’s civic leaders say ‘you can change the city’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

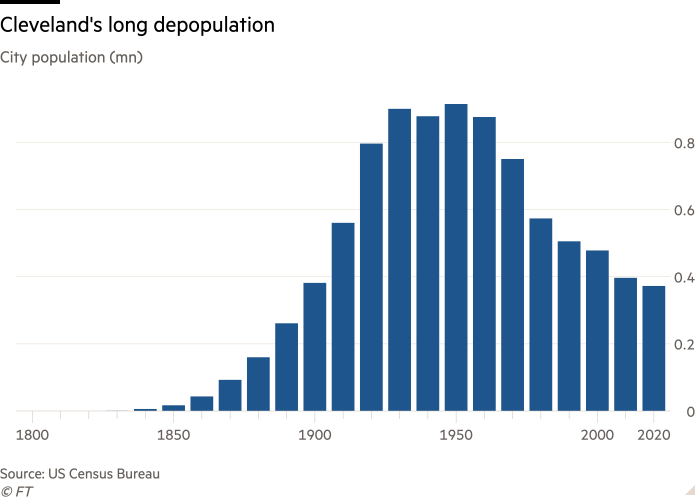

Cleveland stands quietly in north-east Ohio on the shore of Lake Erie. The city was raised on Standard Oil and steel mills, and being a great transportation hub of waterways and railroads. In its heyday, it was the sixth most populous city in the US and, for that reason, became known as the Sixth City.

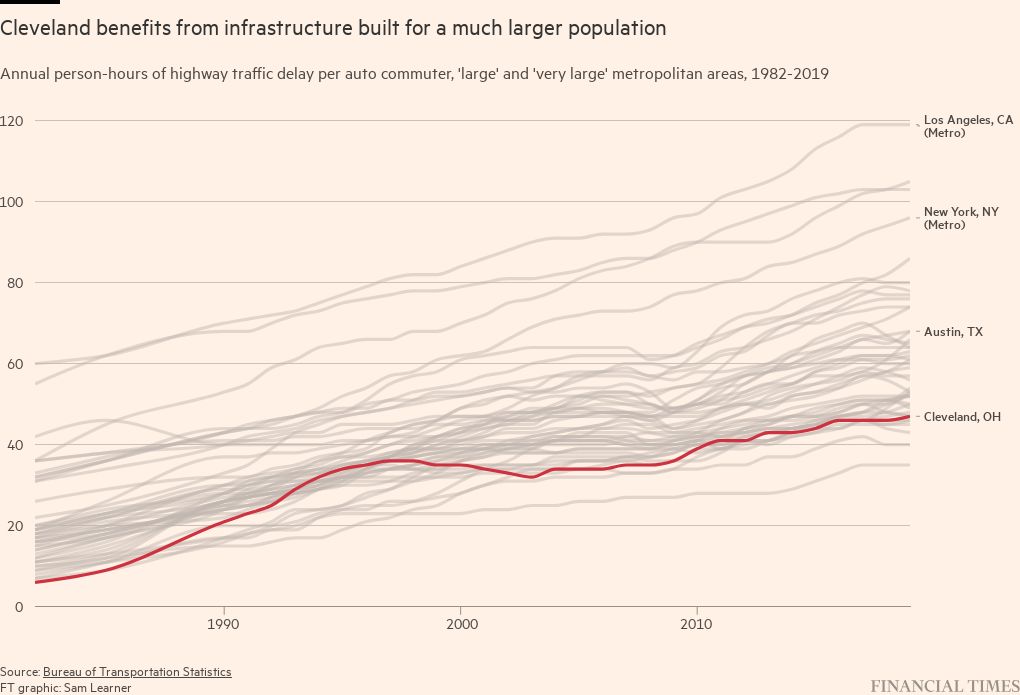

It is now 54th for population but stands at 18th in the latest FT and Nikkei Investing in America ranking, largely on the back of three criteria: affordability, for both individuals and businesses; quality of life, including culture and leisure; and strong scores for climate resilience. It ought to score highly, too, for its residents, who feel empowered to change the place for the good. “This is the era of the midsize city,” says Justin Bibb, Cleveland’s mayor.

The city’s downtown is muscular and handsome, as upper Midwestern cities often are. Art Deco “Guardians of Traffic” sculptures still stand tall on a prominent city bridge, holding vehicles in their stone hands, a nod to the past.

“Cleveland is small enough that you can get your arms around it, but big enough to matter,” says Dan Moulthrop, chief executive of the City Club of Cleveland, an august civic institution.

Speaking in the club’s library overlooking Playhouse Square — a theatre district that features one of the world’s largest outdoor chandeliers — Moulthrop points to the city’s major league sports teams, its world-class arts, its food and craft beer, and the fact that it is all easy to enjoy. “Chicago without the hassle, Detroit without the bankruptcy,” he says. “It’s just fine — in fact, it’s better than fine.”

Of course, Cleveland has its urban problems: lack of affordable housing; vacant commercial property; underfunded transportation and education; and pollution. Bibb says his biggest concern is public safety and gun violence. And the city is grappling to improve its liveability. For example, there is a plan to install bike lanes and trees in the middle of Superior Avenue.

There has also been a change in City Hall — Bibb, 36, took over as mayor last year from the incumbent of 16 years, Frank Jackson, who mournfully stated in 2020: “Cleveland is perceived to be the butthole of the world sometimes.” Moulthrop had wanted to hire Bibb, but did not act fast enough.

“You can come here from elsewhere and join in civic life and make a difference,” Moulthrop says. “I think that is really one of the coolest things.”

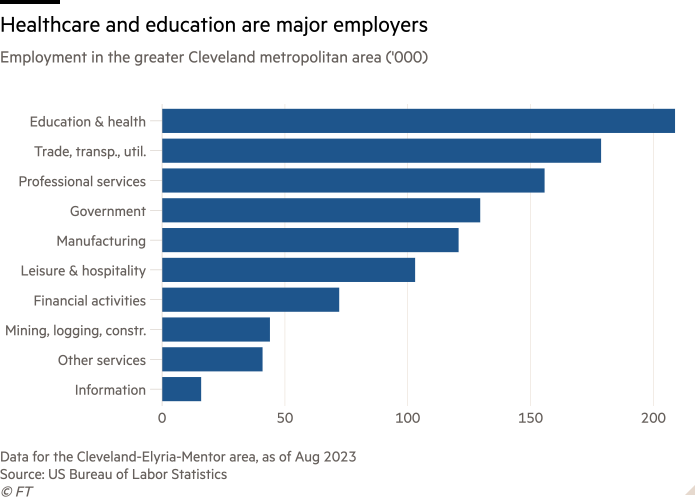

Today, the healthcare industry dominates Cleveland’s economy, which boasts three major hospital systems — Cleveland Clinic, University Hospitals and MetroHealth. Cleveland Clinic is the largest employer in the city and the state. “We are where people come when they lose hope,” says Dr Tomislav Mihaljevic, its chief executive and a heart surgeon by training.

The Healthline bus runs from the chandelier through a long thicket of facilities with glass facades — the so-called Health Tech Corridor — on to the impressive Cleveland Museum of Art. “In the 18, 19 years that I’ve been here, healthcare has been the thing that endures in a way that is always growing, and increasing its market share, and its significance to the broader community,” Moulthrop says.

“If you show up here and are willing to do work, you can change the city,” says Rebecca Maurer, a Cleveland city councillor. “That is just not true in other cities.” Talking at the Red Chimney, a diner in the Slavic Village neighbourhood, which she represents, Maurer says she was elected last year on a platform of “bread-and-butter city services like ‘how long does it take to get a garbage can?’”.

She says she was radicalised years ago by a terrible landlord and a cold apartment. “When I turned in that demand letter and got my heat fixed, I felt like I had a superpower,” she explains.

A Stanford Law graduate, she rejected a “white shoe” law career and entered public service, working for a time on eviction defence at a law clinic. She returned to her hometown to “put in the time and love and effort it takes to try to make a difference here”.

The collective efforts are bearing fruit, argues Maurer. “We have a lot of energy in the city with our new mayor; we have a lot of energy with investments,” she says.

Japanese group Canon, one of whose activities is making medical devices, is eyeing a healthcare subsidiary in the area, describing Cleveland as “a key hub in the country’s medical industry”. Also moving to town from abroad are Seinsa, a Spanish auto parts manufacturer, and Isaac Instruments, a Canadian fleet management company. There is excitement, too, about a new downtown headquarters of Sherwin-Williams, a paint company, and extended bike paths and overdue improvements to the lakefront.

Bibb and Maurer’s goal is to ensure all 360,000 residents reap the benefits of revival. The councillor rattles off a tally of urban problems on her to-do list. “We have seniors who have not seen the lake in 10 years because they have no transportation,” she says. Her aim is to make sure that such facilities “are accessible to everybody”.

“This whole city is filled with people who are trying to make their dreams and their lives happen, despite all of those circumstances,” Maurer adds. But, then, she has to leave, to meet a person suggestive of a similar campaigning spirit: a constituent named Vendetta.

Comments