The appliance of science now centres on Luxembourg’s domestic research

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

At secondary school in Luxembourg in the 1980s, Marc Schiltz was determined to become a physicist — something that would require him to study abroad, like every other would-be scientist in the country.

Amazingly, a prosperous nation with more than half a million inhabitants had no university until the beginning of this century and had spent very little on research.

After a 20-year academic career elsewhere in Europe — France, the UK and Switzerland — Mr Schiltz returned in 2011 to lead what had become one of the world’s fastest-growing scientific programmes, FNR, Luxembourg’s National Research Fund.

During his time abroad, the country had at last established the University of Luxembourg (in 2003) and set public research spending on a path that saw it rise about 15-fold to about €400m a year between 2000 and 2018.

“Although it meant moving from academia into research management, I liked the challenge of coming back to my home country and helping to set up a new research system,” the 49-year-old says. “From a build-up phase that really commenced at the turn of the millennium, public research has now entered its consolidation phase, during which it will have to prove its excellence and quality in a tough worldwide competition.”

For the four-year period of 2018-2021, Luxembourg expects to spend a total €1.5bn on research and development, including block grants to the university and other institutions. FNR’s budget over that period will be €340m.

Luxembourg’s public spending on R&D is now around 0.7 per cent of GDP “which is close to the EU average”, says Mr Schiltz. “We can do a bit better in the future. There is a multi-party political consensus and wide public support for research spending.”

That consensus emerged during the 1990s when Luxembourg was enjoying an economic boom, thanks to its financial sector which thrived as a low-tax haven within the EU.

The country had reinvented its economy twice before, first during the late 19th century when steel production replaced farming as the biggest source of wealth and employment, and then again after the collapse of the steel industry in the 1970s when banking and finance took over. While the latter continue to thrive, Luxembourg’s government began investing in science and innovation to reduce the economy’s reliance on finance through building a high-tech sector.

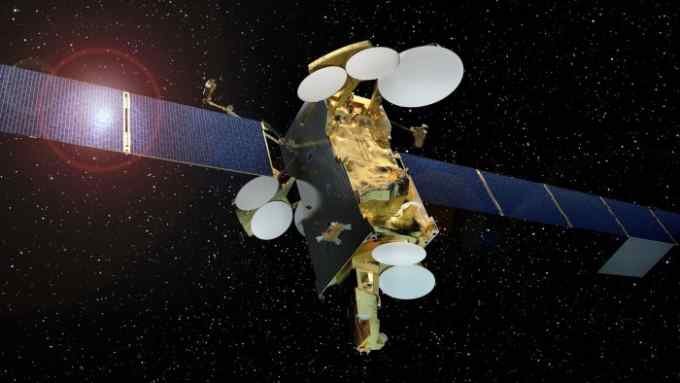

One sign of this diversification was the establishment of the Luxembourg Space Agency last year and the promotion of the country as a destination for space businesses, from innovative satellite operators, to companies that aim to extract resources from asteroids.

“I have to explain to researchers that, as a small country, we cannot do everything,” says Mr Schiltz. “There is flexibility in the system, which helps us to attract scientists to Luxembourg. They tell me it’s a place where they can help to shape the system. We don’t want to be too restrictive but we do have priority areas.”

Some of the priorities reflect the nature of the Luxembourg economy, including the needs of the service sector and now space too. The country is home to SES, one of the world’s largest satellite operators.

Information and communications technology (ICT) is important, with an emphasis on security and data communications in finance and satellite communications. FNR is also funding research into “autonomous systems” including command-and-control technology for robots working in space.

In biomedicine, the emphasis is on “bringing together the life sciences and data sciences”, says Mr Schiltz. A showcase is research into Parkinson’s disease. FNR supports a national study cohort of Parkinson’s patients, whose samples are analysed to find “biomarkers” that indicate different forms of the disease, with different prognoses and different recommendations for treatment. For Parkinson’s, he says, “this is the highest-quality data in the world”.

The geographical heart of Luxembourgish science is the Belval Innovation Campus south-west of the capital. It is the centrepiece of a €1bn urban regeneration project, one of the largest in Europe. Belval houses the university, research centres and business incubators.

A feature of national life is its outward-looking cosmopolitan attitude. Non-Luxembourgers make up almost half of the population and Mr Schiltz was determined that an outward-looking attitude should apply to science, too. “There was a certain risk in setting up a research system in Luxembourg that could become inward-looking,” he says. So international links were emphasised from the start. That was demonstrated in 2017 when Mr Schiltz was elected head of Science Europe, the association of European research funding organisations. “Their collaboration can impact the future of Europe in a way no single organisation would be able to achieve on its own,” he says.

Over the past 15 years, the outflow of talented Luxembourgish students to the rest of the world has been reversed. No less than 80 per cent of scientists in Luxembourg are foreign nationals. The Marc Schiltz equivalents at school today will be able to experience an international scientific programme as students in their own country.

Comments