New-generation Palestinian artists use birdsong and bonsai trees to cross boundaries

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A smuggler netted at a checkpoint pulls up a trouser leg, opens a pouch strapped to his shin and releases a series of goldfinches. Liberated from their mobile prison, the particoloured birds — lucrative goods on the black market — take flight under the eye of a customs official, as though the captive were a magician conjuring beauty from desperation.

The scene is from Dina Mimi’s short film “The melancholy of this useless afternoon chapter II”, which samples footage of contraband seizures on the crossing from Jordan to the West Bank, cut with shots of finches lured into traps or windswept grass filmed from a plane during take-off, to a soundtrack of birdsong. The video forms one element of a poetic installation exploring affinities between smugglers and fugitives, their daring escapes and the nets in which both are caught.

The innovative piece is running at the Mosaic Rooms in London as part of In the shade of the sun, a group show of freshly commissioned work by new-generation Palestinian multimedia artists. They were proposed by Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, artistic collaborators born in the diaspora and now working between New York and Ramallah in the West Bank. Their own show, May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth, rethinking the archive in the internet age, was at MoMA in New York last year.

The four chosen artists are part of Bilna’es (“in the negative” in Arabic), an initiative they helped found during the pandemic, Abou-Rahme says, to expand support for “emerging artists, musicians and writers with a Palestinian focus”. The aim is self-sufficiency through publishing — both physical and online — from pamphlets to music and video games. Makimakkuk, a pioneering female vocalist-rapper in Ramallah’s thriving electronic music scene, was to have opened the Mosaic Rooms show with the premiere of a new sound work, “What remains in the museum”, but was denied a British visa.

“We haven’t curated this show,” Abou-Rahme says of In the shade of the sun, which emerged from the duo’s own struggles to gain institutional support for cross-disciplinary art forms. “We’re trying to question rigid separations, to make a space where musicians, artists and writers can be together.” The experimental approach of the four artists makes funding precarious, wherever they are based, she says. Or else, Abbas adds, they “veer towards something they can sell to survive. Palestine is an extreme case of what happens everywhere; the conditions are amplified.”

Opposite Mimi’s 11-minute film of bird-smugglers, another screen shows chapter one of her installation. Shot in Amsterdam, where the Jerusalem-born artist is resident, this video has silent footage of birdsong competitions inspired by a Surinamese custom, using caged songbirds. The spoiled 16mm film creates an abstract blizzard, whose random flashes recall birds in flight, set to an upbeat, rhythmic soundtrack of revolutionary songs from Oman, Yemen and Palestine.

The artist’s voiceover recalls her first experience of loss, alluding to the political barriers and spatial engineering of the occupied territories: “As a child I listened but never understood.” Moving, aged nine, “from one city to another”, she was separated from a friend, Dalia, whom she phoned only once. “It felt she was too far away, but it was only half an hour.”

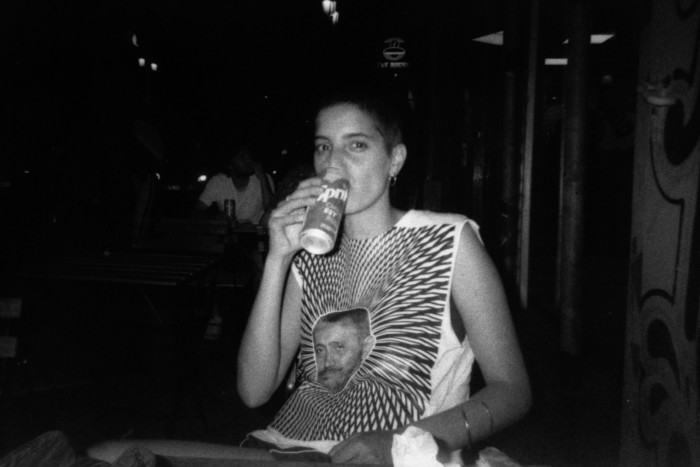

The films were inspired, Mimi says, by her brother’s obsession with birds, her own experiences of the Jordan crossing and the 2021 escape from a high-security Israeli prison of Zakaria Zubeidi, a leader in the second intifada of 2000-05 and co-founder of the Freedom Theatre in Jenin, who tunnelled out with a spoon before being recaptured. Between the two screens is a framed relief: a beige vest incorporating a net, like those in which finches are hidden, though here sculpted from a dried cactus. The unifying sculpture hints that what is also being smuggled and caged is the human body, as the work’s focus of identification shifts between bird, black-marketeer, displaced child and hunted fugitive. One film is dedicated “to all the goldfinch smugglers”.

By contrast, “Tomorrow, again” (2023), a 10-minute video by the Haifa-based artist Mona Benyamin, presents itself as “breaking news from Palestine”. Part mordant skit, part meditation on time and trauma, the film uses the artist’s parents in its surreal take on a prolonged state of emergency in which facts are endlessly disputed. A newsreader weeps, eyewitnesses clash and talking heads yell as a Palestinian person is reported to have “executed an operation” in East Jerusalem. Footage inside a bus of a man boarding and planting an already smoking device repeats on a loop. Clock hands whirl. The absurdist work pushes to disturbing limits a tradition of darkly comic political satire whose roots can be traced to a 1974 novel by the Palestinian-Israeli Emile Habibi, The Secret Life of Saeed: the Pessoptimist.

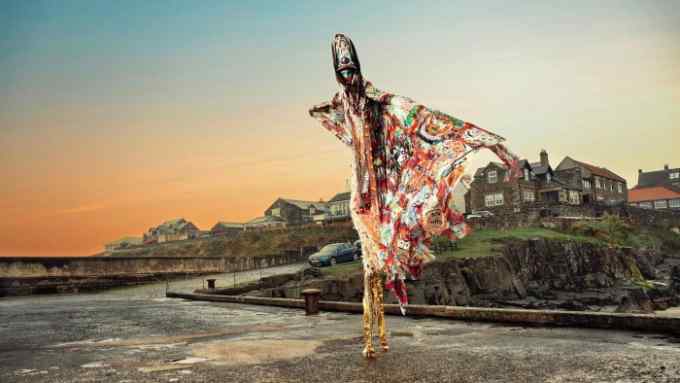

Bilna’es’s “adisciplinary” approach is epitomised by Xaytun Ennasr, an artist schooled in Jenin and based in Washington, DC, who works across text, drawing, sculpture, ceramics, embroidery, games and even horticulture, describing their tools as “sci-fi-folklore”. The centrepiece of their beguiling, protean installation, “Revolution is a forest that the colonist can’t burn” (2023), is a gnarled, 150-year-old olive tree, flanked by bonsai fig trees in ceramics made by the artist. The pots’ stylised symbols of landscape and stars are harmoniously echoed in textiles and in 12 drawings, each bearing an Arabic line from a poem by the artist which gives the work its title.

A touchscreen video game allows visitors to plant a virtual tree in a barren landscape, collectively restocking a forest with their fingertips. Replicating the therapeutic effect of actual horticulture, the deeper aim is to challenge rapacious attitudes towards the land, through an aesthetic the artist terms “radical softness”.

Ennasr, whose day job is as a UX (user experience) designer, says that whereas trees tend to be depicted in video games “as resources to be extracted or obstacles to be removed”, here you “start with an already extracted landscape, grow a tree and give it stewardship”. The real plants, meanwhile, form a “living sculpture of Palestine”. For this versatile artist, as perhaps for Bilna’es, “using different mediums and materials helps create a world of the imagination outside the forces that present themselves as immutable, but are more fragile than they might seem.”

To January 14 2024, mosaicrooms.org

Comments