Its blockbuster cystic fibrosis treatment costs $300,000 a year. Now Vertex wants to solve the opioid crisis

Simply sign up to the Pharmaceuticals sector myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

So effective is Vertex Pharmaceuticals’ blockbuster cystic fibrosis (CF) drug, Trikafta, that studies project it could extend the lives of some young patients by up to 45 years. As such, it is not cheap: in the US, it costs $300,000 per patient, per year. But given the transformative nature of the treatment for a disease with a poor prognosis, the high list price has not held back sales for the pharma group.

And, now, the same team of scientists at Vertex’s San Diego laboratory have a second decades-long research project coming to fruition that could unlock another potentially huge market: non-opioid painkillers.

If patients live longer, “it’s good for business”, says David Altshuler, Vertex’s chief scientific officer. The number of people living with CF worldwide is now 105,000, up from 70,000 in 2012, according to estimates from US non-profit the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation — a rise that experts attribute both to Vertex’s drugs and improved diagnostics.

“If you take a life-threatening disease that shortens life and you have a transformative medicine, you not only have the benefit in the short run, but then people live a long time and it’s a positive thing for everyone,” adds Altshuler. These positive effects are evident in Vertex’s revenues, which more than doubled between 2019 and 2022, from $4.2bn to $8.9bn, the period covered by the FT-Statista ranking of the Americas’ 500 fastest-growing companies. Revenues then rose again, to $9.9bn, in 2023.

Since its launch in 2019, Trikafta has generated $26bn in revenues and is expected to hit $10bn in annual sales next year. The Boston-based biotech is also poised to seek regulatory approval this year for its fifth CF treatment, known as the vanza triple, which is also projected to generate nearly $10bn in annual sales, according to investment bank William Blair.

Vertex “is probably going to be one of the fastest-growing top lines outside of the weight-loss drugmakers [Eli] Lilly and Novo [Nordisk],” predicts Debjit Chattopadhyay, a healthcare analyst at Guggenheim Securities. “I’d put Vertex in my pharma top three [to invest in].” This year, Vertex’s market capitalisation surpassed $100bn for the first time.

Daniel Lyons, a portfolio manager at Janus Henderson, a top-25 Vertex shareholder, says the biotech faces “no real competitive threats” to its dominance in CF, with patents extending until at least 2039.

“That gives the company an incredibly profitable base business and they’ve basically reinvested a significant amount of those profits in their pipeline.”

Altshuler says Vertex learnt the importance of continued investment in research from the troubled rollout of its hepatitis C treatment, Incivek. After becoming the fastest drug ever to hit $1bn in annual sales, it was rapidly supplanted by a superior treatment from rival Gilead. “It’s never the case that the first or second medicine is the best — but most companies think that no one’s going to keep with them so they stop,” he says. “We learnt from that: never assume you’re going to win; keep building better and better medicine.”

However, Vertex has come under fire for the hefty price tag of Trikafta, which has meant only 12 per cent of CF patients worldwide have been prescribed the treatment, according to research published in the Journal of Cystic Fibrosis in 2022.

The researchers concluded that “the medicines are so expensive they are essentially unavailable unless reimbursed by government or health system authorities”. Altshuler says the “vast majority” of CF patients worldwide who meet the prescription criteria for Trikafta have been prescribed the drug.

The challenge for Vertex is whether it can reproduce its success in CF in other diseases. The company received regulatory approval last year for the first ever treatment based on Crispr gene editing, which targets sickle cell disease and beta thalassaemia. It also paid $4.9bn this month for Alpine Immune Sciences, which is developing a treatment for an autoimmune kidney disease.

But it is a new generation of non-addictive painkillers that analysts say are the most promising drugs in Vertex’s pipeline.

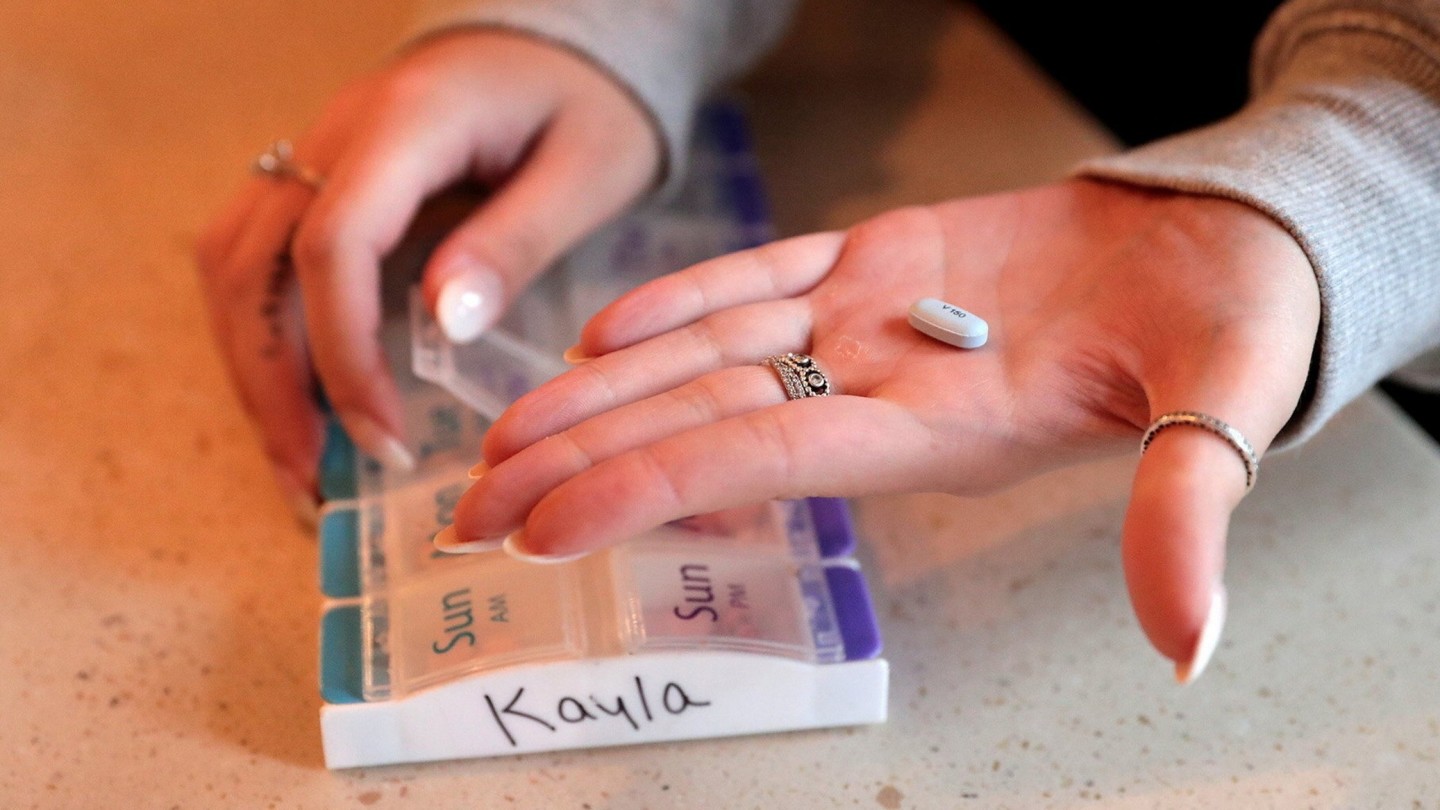

Vertex hopes to receive US Food and Drug Administration approval for a non-opioid painkiller, known as VX-548, this year after a late-stage clinical study showed it lowered pain with a far lower incidence of side-effects such as nausea and vomiting — and without the risk of addiction.

“Each year, we’re layering on evidence that we’re going to crack another disease open,” says Stuart Arbuckle, Vertex’s chief operating officer. He says Vertex’s $4.8bn R&D budget is not about maximising “shots on goal”; it is instead focused on “a set number” of diseases where Vertex has “super-high conviction that they’re going to work”.

Vertex’s acute pain drug is projected to generate $2.3bn in annual sales by 2030, according to analysts’ consensus forecasts, but the much bigger opportunity is an approved non-opioid painkiller that can serve as an alternative to the prescription opioids that have led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Americans.

“Wall Street is all over the place with how to handle chronic pain, because of the dirtiness of the opioid crisis and because people have gotten bullish on pain launches and the pain launches have failed,” says a person at a biotech fund with a shareholding in Vertex.

To overcome competition from cheap generic opioids, Vertex has hired a salesforce of several hundred people — much larger than its team focused on CF — to work on the product’s launch.

Some analysts say non-opioid pain medication could be the next blockbuster class of drugs, with an impact on the industry similar to the weight-loss medications. “Pain could be analogous to another GLP-1 scenario,” says Hartaj Singh, a biotech analyst at equity research company Oppenheimer — referring to the hormone targeted by the weight-loss drugs. “If you can go from acute to chronic pain, we could be talking about a $10bn-$20bn revenue potential.”

Altshuler recalls how experts dismissed GLP-1s. “What they said . . . ten years ago, was that no medicines for diabetes and obesity are needed — they’re all generic, nothing really works, it’s not going to happen. That turned out to be untrue . . . I can’t promise but, to me, [the pain franchise] looks like [CF] in 2012.”

Comments