Catastrophe bond returns rebound as hurricanes miss US east coast

Simply sign up to the Capital markets myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

A mild hurricane season in Florida and soaring interest rates have propelled catastrophe bond returns to record levels this year, reversing a slump in the prices of these niche debt instruments late last year.

Catastrophe bonds were first created in the 1990s as a way of transferring risk from insurers to investors. It was realised there was a need for such a risk transfer after Florida was hit in 1992 by the category five Hurricane Andrew — at the time, the highest category, and the most expensive, hurricane ever to hit the US. It caused eight insurance company collapses.

On one side of the trade are the insurers (or businesses and governmental bodies) seeking protection from catastrophe-linked losses. On the other are investors willing to take on that risk, and those losses, with their own capital, in return for regular interest payments.

According to the Swiss Re catastrophe bond index — the main benchmark for this market — today’s investors in outstanding bonds enjoyed a record 16.2 per cent return between the start of the year and the second week of October.

“With just over two and half months of returns to add to the 16.2 per cent already delivered, the catastrophe bond market is now in sight of a stunning roughly 20 per cent, or even more, in total investment return for 2023,” noted Artemis.bm, a specialist provider of information on insurance-linked securities, in a report last month.

Artemis also pointed out that the Swiss Re catastrophe bond index had already recorded a 10.3 per cent return by the end of June, setting a new record for any half-year.

In the US, losses between now and the end of 2023 are unlikely. Although the north Atlantic hurricane season does not officially end until November 30, so far only one major hurricane has hit Florida this year — and it struck in a relatively remote part of the state.

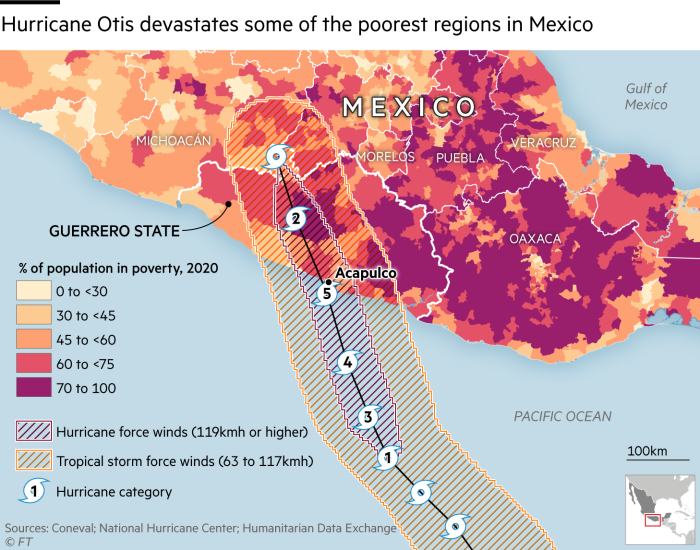

However, the record strength Hurricane Otis that smashed into Acapulco in late October could be costly for insurers. Damage estimates are still being worked on, says Moody’s, although the rating agency has already compared this hurricane’s intensity to a similarly strong storm that hit Mexico in 2005, causing insured losses of about $2.7bn — making it the costliest hurricane in the country’s history.

These days, catastrophe bonds may be bought by big pension funds and hedge funds, but they can still leave investors with huge losses. Once an insurer is hit by a catastrophe that causes a preset amount of damage, the investor becomes liable. Last year, Hurricane Ian caused an estimated $35bn-$55bn of damage, Fitch Ratings found — second only to the damages left behind by Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

Catastrophe bond prices fell sharply after the losses incurred from Hurricane Ian. The market had been relatively stable over the previous 20 years, but Hurricane Ian “will go down in history as one of the costliest storms” — with the largest negative impact on the Swiss Re index — Credit Suisse explained last year.

Many big investors “pulled back” after that scare, recalls James Eck, a vice-president and senior credit officer for financial institutions at rating agency Moody’s. And climate change is now expected to act as a continuing headwind for the market, as weather becomes more extreme. Between 1980 and 1989, the average number of natural catastrophes a year, worldwide, was more than 70 — but between 2013 and 2022, it jumped to about 200 a year, according to Swiss Re.

As more vulnerable areas on the US east coast are being insured, “the trends [in extreme weather] frequency and severity are headed up”, Eck suggests.

Despite this, in 2023, the catastrophe bond market has enjoyed a comeback. Issuance in the first six months of the year was a record $10bn, according to rating agency Moody’s. That is more than the total for the calendar year 2022, according to Swiss Re.

One reason for the resurgence of demand was that Hurricane Ian losses were not as acute as initially estimated, according to Swiss Re in a recent report. “In fact, there have been minimal losses to [catastrophe] bonds due to Hurricane Ian,” the reinsurance group said, adding that many bonds that primarily cover Florida were heavily marked down after the hurricane but continued to regain value in 2023.

Another big catalyst for catastrophe bonds has been rising interest rates. The vast majority of catastrophe bonds offer floating rates, meaning that their yields can be put up in line with Treasury bond yields, without their prices falling. So, while the US Federal Reserve’s interest rate rises have been punishing for fixed-rate bonds, they have “been a big benefit for the last year” for catastrophe bonds, says Eck.

With the north Atlantic hurricane season now winding down, the catastrophe bond market looks set to remain strong going into 2024. This year’s hurricane season has been “benign”, says Charles-Marie Delpuech, an associate director at S&P. “We did not really have a major hurricane this season,” he observes. As a result, “we don’t see why the issuance of cat bonds would decelerate. There is definitely demand.”

The benefit from higher interest rates “will override concerns that the growing frequency of extreme weather is ratcheting up the risk of loss”, argues Claude Brown, a partner at law firm Reed Smith. “There has been a recent surge in interest in catastrophe bonds.”

Catastrophe bonds are still prone to volatility when extreme events follow one another in quick succession, Brown warns. “But we’re talking about mature investors who will have priced in, and accepted, potential losses when making investment decisions,” he adds. “This isn’t a kind of ‘wild west’ of weather, but rather an established product growing in popularity.”

Comments