Emerging markets borrowers sell debt at record rate in January

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is part of the FT’s Runaway Markets series.

When Saudi Arabia announced it would sell $5bn of international bonds this week, investors scrambled for a piece of the action.

The gulf nation drew in about $20bn of orders for its 12- and 40-year bonds, helping it reduce the borrowing costs it paid on the debt, people familiar with the matter said.

Saudi Arabia’s feat is just the latest in a string of successes for emerging-market borrowers, who have rushed to tap international capital markets this year in an attempt to lock in low interest rates.

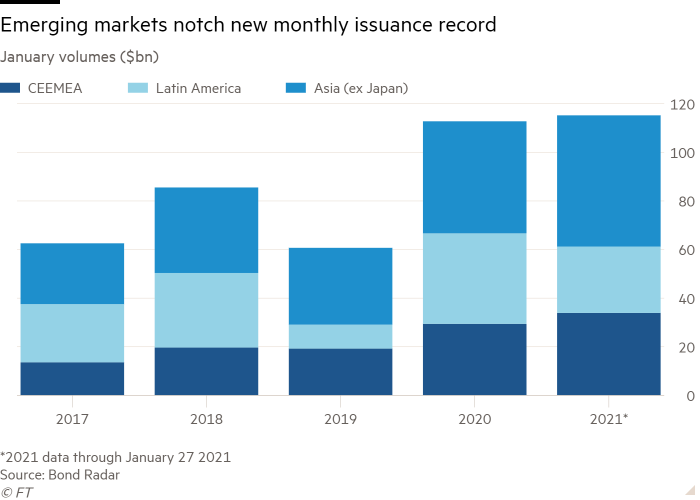

Governments and companies in the developing world have sold a record $115.23bn of international bonds in the first 27 days of 2021, surpassing the previous all-time monthly high of $112.78bn set last January, according to Bond Radar data stretching back to 2003.

“For all intents and purposes, this is a tsunami we’re facing now,” said Sergey Goncharov, an emerging markets portfolio manager at Vontobel Asset Management.

Two factors have supercharged the typical January bond rush, bankers and investors say. First, cash-strapped governments had to increase their borrowing as the coronavirus crisis battered public finances.

Second, an early-year sell-off in the US Treasury market, which sent benchmark 10-year yields to their highest level in roughly 10 months, served as a reminder that the era of rock-bottom bond yields in the developed world — which has driven investors into the emerging world in search of returns — may not last for ever.

“From a borrower’s perspective, it’s a great time to lock in rates before yields move up,” said Stefan Weiler, head of central and eastern Europe, Middle East and Africa debt capital markets at JPMorgan. “It’s hard to imagine the market getting any better. We have probably seen the bottom on rates, and a lot of spreads are close to all-time lows.”

Saudi Arabia sold its 12-year bond at a yield of 1.3 percentage points above 10-year US government debt. The 40-year issue was priced at a yield of 3.45 per cent. The country joins borrowers such as Mexico, Colombia and Indonesia in issuing big chunks of new debt in the first few weeks of 2021.

Many of its fellow Middle Eastern governments have done the same — including lower-rated issuers like Oman and Bahrain, which both sold 30-year debt.

“Some of those Middle Eastern borrowers have had the double hit of Covid and the oil price so they account for a lot of the increase in issuance this year,” said Anthony Kettle, a senior portfolio manager at BlueBay Asset Management.

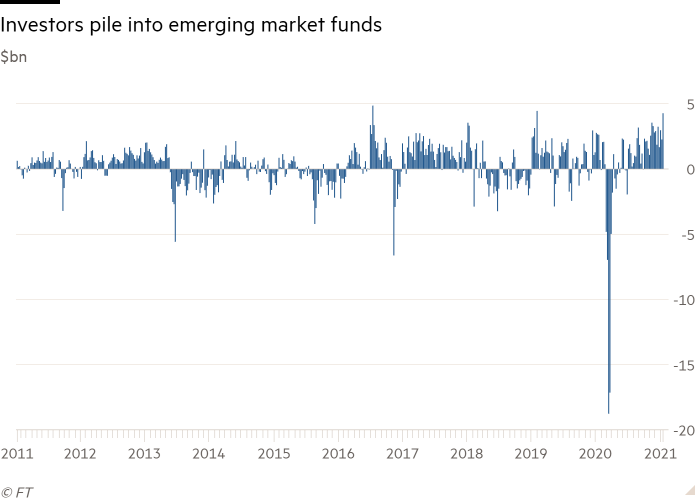

Investors have eagerly snapped up the new supply, according to Andrea DiCenso, a portfolio manager at Loomis Sayles. Data from EPFR show that investors have poured $4.3bn into funds that invest in emerging market bonds for the week ending January 20, the largest sum in nearly two years and the 16th consecutive week of inflows. That brought the total for the first three weeks of 2021 to roughly $9bn.

The clamour from investors underscores their confidence that the recent Treasury sell-off will not snowball into a rerun of 2013’s “taper tantrum”, when a spike in US bond yields battered emerging market bonds.

Runaway Markets

In a series of articles, the FT examines the exuberant start to 2021 across global financial markets

Fears of a redux percolated earlier this year when a handful of regional Fed presidents signalled the possibility that the US central bank could begin to withdraw its support from financial markets as early as this year. Most market participants assumed the Fed would hold off on scaling back its $120bn-per-month asset purchase programme until at least 2022.

Senior Fed officials — including chairman Jay Powell — have since gone to great lengths to damp down speculation of an earlier-than-expected retreat, but some investors fear the issue will rear up again, especially as the economic recovery gains pace.

“It is not hard to see that with the vaccines being rolled out we are unambiguously going to get stronger growth going forward,” said James Barrineau, head of global emerging debt strategy at Schroders. “You put that together with where yields are, with supply being incredibly abundant and the Fed potentially responding to stronger growth by dropping hints that they might be tapering towards the end of this year, and all of this lends some urgency to issuers to get their business done.”

Tell us. What else would you like to learn about this story?

Complete a short survey to help inform our coverage

What is notable about the recent spate of bond sales, according to Mr Barrineau, is that many countries have sought to sell longer-dated bonds. Beyond Saudi Arabia’s 40-year bond sale, Mexico and Indonesia opted for 50-year notes, while Chile joined its Middle Eastern counterparts in selling 30-year debt.

“The incentives are to go as long in maturity as you possibly can,” he said. “It is best to tap [the market] now and then not have to worry about having to refinance any time in your lifetime.”

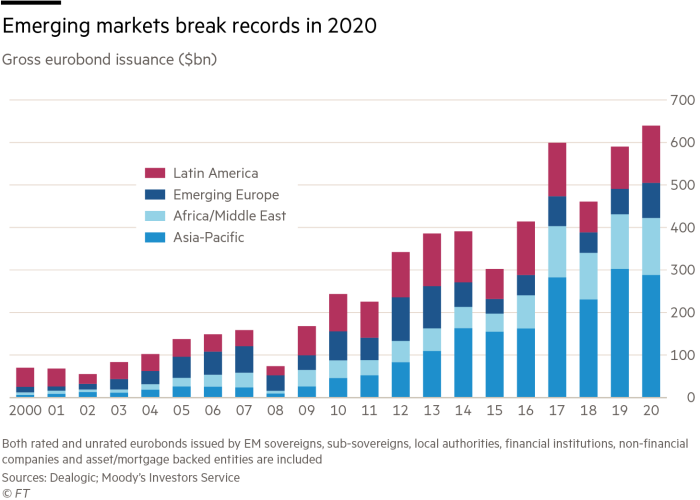

The record pace may slow, however, as the year progresses and economies globally begin to heal, analysts at Moody’s predict. While they still forecast robust issuance in 2021, they project volumes will fall short of the all-time high of $639bn emerging market borrowers raised on international markets last year.

Vaccine delays and lengthier lockdowns that stunt the economic recovery could also damp activity and dent demand for riskier assets, investors warn.

“Countries realise they better satisfy their financing needs when the sky is blue because you never know what will come your way,” said Alejo Czerwonko, chief investment officer for Latin America at UBS Wealth Management.

Additional reporting by Nikou Asgari

Comments