Danger and delight: a dispatch from Antarctica

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Leo Houlding, Mark Sedon and Jean Burgun are three weeks into a groundbreaking expedition to kite-ski across Antarctica and climb one of the world’s most remote mountains, the Spectre

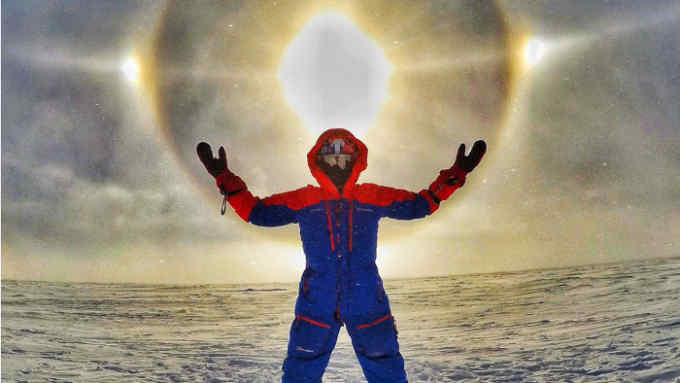

Finally, 13 days after the aeroplane dropped us in the midst of the high-polar plateau, we caught our first glimpse of the Spectre. Mark went ahead to film our glorious arrival, skiing behind our kites and hauling massive sleds across the glacier towards the mountain of our ambition.

Suddenly I was yanked violently backwards. I tried to use the kite to fight the pull but it was useless. I looked around and to my horror saw my pulk [sled] had vanished through the snow into a crevasse and was pulling me towards it. I was reaching down to try to release it when to my great relief I came to a halt — the pulk had lodged on a deep snow bridge before I had been pulled after it down into the icy depths.

Jean came to my aid and within a couple of hours we had descended into the crevasse and hauled out my heavy pulk. Remarkably nothing was damaged and I was fine. Had I lost my pulk, it would have been an evacuation scenario. Had I been pulled down the crevasse too, it could’ve been much worse. Less than 1km from the end of the kite journey we were so nearly struck by disaster. As Jean says: “Irony always wins.”

We are currently camped in one of the most spectacular and remote places one could possibly imagine. I’m typing on my iPhone in my tent, sending this through a 3.5 kbps satellite connection. The Spectre looms ominously above, both magnificent and menacing. When bathed in sunlight and free from wind, it is the most perfectly beautiful mountain. But when the sky darkens and the freezing wind blows, the Spectre’s towering ramparts cast a murderous shadow. You simply will not survive for long out here in a storm without shelter.

The weather has been far more unstable than we anticipated, changing drastically about every six hours. Our original objective, the South Pillar of the Spectre, is a huge and difficult wall. To attempt it in the light and fast alpine style for which we are equipped, when we are so remote and exposed, we would need a spell of stable, good weather. Without that, it is a level of commitment too far.

Therefore we decided to focus on the less imposing north side of the mountain, previously climbed only once, in 1980 (the year I was born), during a US geological expedition. Professor Edmund Stump and his late brother Mugs, one of the finest alpinists of his day, spent five weeks exploring the geology of these mountains by snowmobile after being dropped off by Hercules skiplane. They made several impressive climbs including the Spectre, for which they also suggested the name.

The day started out sunny and calm, making the peaks much less intimidating. We set off at 8am and accessed the upper part of the mountain via the same couloir as Ed and Mugs. It is a complex, steep face of rock walls and snow chimneys. Although there were clearly lots of possibilities, we could not see a continuous line to the top and from close up it appeared much steeper and harder than from afar. Following what we felt was the most logical line, we soon found ourselves in much more serious terrain than we were expecting. Jean led a difficult section of mixed climbing. Using crampons and ice axes designed for ski touring to climb vertical rock interspersed with ice and snow is extremely challenging. The sky clouded over worryingly fast, though it remained dead calm. I led up a snow chimney, wedging myself between vertical rock and snow that crumbled beneath my feet — falling not an option here — as the weather continued to deteriorate.

We began to feel extremely vulnerable and exposed. High on that difficult peak at the far end of the Transantartic mountains, it is fair to say we were probably the most remote humans on Earth, with no hope of help or rescue if anything were to go wrong.

Leo Houlding: Updates from Antarctica

Rules of exploration

As he sets out for the world’s most remote mountain range, the climber hopes to pioneer a new era of polar adventure

Life in the freezer

In his first dispatch, Houlding finds his meticulous plans coming up against the harsh realities of the coldest continent

When we felt for certain we must be close to the summit, we struck a 25-metre-tall vertical cliff. Already facing a long, complex descent from this point, pushing further started to feel deeply committing. Had the freezing wind kicked up then we would certainly have retreated, but even with thick cloud, the lack of wind gave us the confidence to continue with the hardest section.

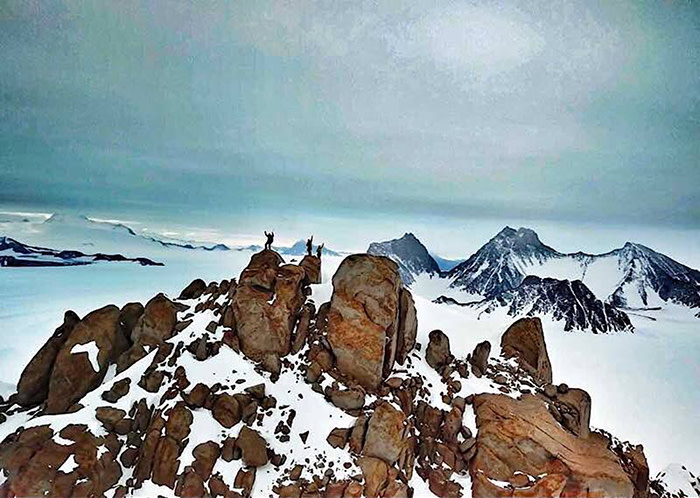

A long, spectacular ridge traverse led around a block the size of a house and then, finally, on to the summit. In truth, it was not a joyous moment. We all felt extremely anxious about our descent and being so completely at the mercy of the weather. We could see our camp, our survival zone, so tiny and so far below. With little celebration we turned and descended the final section of the ridge, then began rappelling down.

We arrived back at our tents after a 21-hour round trip, exhausted, relieved and happy. Almost immediately the wind began to blow again.

The bad weather that has dogged us meant the kite journey to get here took twice as long as expected and that has greatly limited our climbing time. Jean and I managed to grab the second sunny day in three weeks to make a difficult but enjoyable first ascent of one of the other Organ Pipe peaks — previously unnamed as well as unclimbed.

And now, so soon, we must depart this most beautiful and hard-to-reach arena. For $100,000 we could be collected by aircraft from right here, but we don’t have that money and that is not our quest. Tomorrow we begin a 300km walk on skis pulling 100kg pulks back up to the hostile high plateau. We hope to be at our drop-off point in 20 days. There we should pick up the favourable katabatic winds to enable us to kite the 1,100km we need to cover before our expedition is over. I am beginning to wonder what I was thinking. But spirits are high and we are proud of our time in these mountains. We have summited safely and cautiously and now we begin the long journey home to our families. That is a satisfying and wonderful feeling.

For the full background on the expedition see ft.com/spectre. For a live map, see spectreexpedition.com

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments