The value of collecting is not in the dollar signs

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When the Titanic plunged into the frigid ocean waters south of Newfoundland more than a century ago, the musicians of the great ship’s orchestra stoically played on — upholding their art, but failing to acknowledge the world collapsing around them.

Today, you might wonder whether we are culturally, politically and ecologically arriving at another such moment of peril, with a world awash in unrest, a climate crisis devouring our coastlines, fires ravaging our forests, and existential questions about racial and income inequality.

And yet, amid it all, the art collecting world appears to thrive. Major galleries continue to expand, the art fair and auction circuits hum, and new generations of artists are rolled out like planes taxiing for take-off. The dollar signs can seem obscene.

One must then ask: How can collecting art — a personal passion and luxury — serve this world in turmoil, rather than become an emblem of excess in a stratified society of haves and have-nots? How might the art world play a more assertive role in what we see as the crisis in the culture? How should artists, collectors and gallerists grapple with this existential threat to the sustainability of the greater art world?

Let’s be clear: some artists, collectors and gallerists — myself included, as a gallerist for the past 30 years — benefit greatly from this gilded age, and I might be viewed as an odd messenger in urging a reconsideration of our role and responsibilities. But it is a false choice to suggest that we must be either art barons or principled paupers. I am neither, and I want the legacy of my time on earth to be shaped by meaningful things. That includes the art I so cherish.

To that end, the value of collecting for the greater good is not about hunting trophies, where the price of a work and the notoriety of purchasing a famous piece supersedes the meaning of the object. I am talking about understated, serious collectors who assemble collections in the pursuit of their passions, and who create legacies by nurturing and uplifting people, not things. What these people do with their collections can change lives.

The artist Kehinde Wiley epitomises this. Wiley’s sculpture “Rumors of War” is emblematic of his vision. This monumental bronze, dramatically unveiled in New York’s Times Square last autumn, was permanently installed in December at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, Virginia, once home base of the Confederacy. The sculpture — a contemporary African American man sitting unbowed atop a muscled horse — now confronts the prominent Confederate statues along Virginia’s Monument Avenue. The confluence of collectors that have supported Wiley for decades, alongside the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, have helped to create a new art ecosystem that moves beyond the relics of America’s chequered past and embraces a future that includes and celebrates all people, cutting through the noise on issues such as racism, inequity and justice.

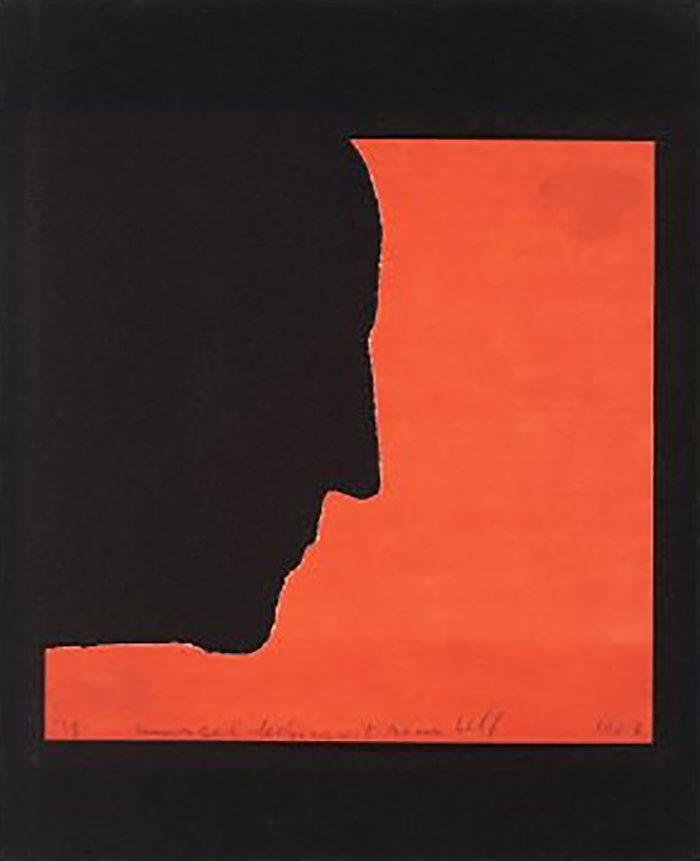

A hundred miles north in Washington, DC, the longtime collectors Barbara and Aaron Levine have made their own grand gesture, donating their treasured collection of works by the 20th century’s greatest artist, Marcel Duchamp, to the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum, which is free to the public. The gift includes an endowment for education, particularly intended for the young: generations of people will be enriched by this gift.

In 2017, Agnes Gund, one of the art world’s most beloved and generous philanthropists, set a remarkable example of how one’s passion for collecting can transform into meaningful social change. Selling a treasured Roy Lichtenstein painting for more than $150 million, she used the proceeds to establish the Art for Justice Fund, dedicated to reducing prison populations across America and bolstering employment and education opportunities for former inmates.

Then there’s Pamela J Joyner, a self-proclaimed “activist collector”, in San Francisco. She has assembled one of the pre-eminent collections of work by African American artists and artists from the African diaspora. As a vocal advocate for traditionally under-represented artists, Joyner works closely with institutions to advance demonstrable change in their acquisition and exhibition policies.

These are just a few of many changemakers who can get lost in headlines adorned with jaw-dropping price tags and other digital catnip. They are the art world’s real currency.

Responsible collecting today is about more than just taking an honourable approach and eschewing ego-driven acquisitions. It’s about creating new opportunities and even supporting entirely new art ecosystems. It’s about making decisions and taking actions that unleash the type of art, and artists, that can inform our public conscience and bend history.

Over the past two years, I’ve interviewed more than 25 collectors from all over the world for my podcast Collect Wisely. We don’t talk about the price of an artwork, and we don’t focus on artists we represent. Beyond that, everything is on the table. The conversations have focused on climate change and lamented the state of our world in crisis. One word, connoisseurship, has come up often. The collectors’ motivations vary greatly, but time and again, I’ve witnessed something that always seemed intuitive to me — that collecting is more than a desire to acquire. It’s about educating, sharing and investing in artists who have something to say.

As another season of auctions and art fairs unfolds, all this is worth careful consideration. Certainly, there are reasons to be cynical about the art world, the price of art, and what can seem like the frivolity of it all against the backdrop of this moment. But know, too, that art can shape history and change minds. Art can empower the powerless and hold the powerful to account. Art can educate, inspire, expose and elevate. Speaking personally, I can attest to the fact that art can nourish a young soul from a difficult and challenging childhood.

I’m not naive enough to believe that collecting is a life raft, but in a world dark with fear and beset with uncertainty, art can most certainly be our North Star.

Sean Kelly is a New York-based gallerist

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Listen to our culture podcast, Culture Call, where editors Gris and Lilah dig into the trends shaping life in the 2020s, interview the people breaking new ground and bring you behind the scenes of FT Life & Arts journalism. Subscribe on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you listen.

Comments