Käthe Kollwitz, MoMA review — incandescent art fuelled by grief and rage

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Käthe Kollwitz, who understood how inseparable love is from grief, entwined the two in a lifetime’s worth of unsettling, darkly seductive images. She packed a whole range of incandescent feeling into black-and-white drawings, inky etchings and desaturated lithographs. “I have never done any work cold,” she once said. “I have always worked with my blood, so to speak. Those who see these things must feel that.” Well, not everyone who sees them: the implacable George Grosz dismissed her as “teary-eyed”.

Kollwitz, the subject of an ardent, insightful and melancholy retrospective at MoMA in New York, knew her way around pain. A sister who lost a brother, a mother who lost one child and nearly another, a witness to inconceivable loss through two world wars, Kollwitz wrenches the guts of all but the stoniest viewers. Yet her sheer technical confidence and emotional precision are cheering, too.

Born in 1867, she spent most of her life in Berlin, but didn’t hang with the artsy crowd. She and her physician husband, Karl Kollwitz, lived among his working-class patients and got a close-up look at poverty, exploitation and hunger. That experience provoked a constructive rage. In the 1890s, she published her first print portfolio, which chronicles a failed 1844 rebellion of Silesian weavers by portraying conditions that had changed little in 50 years.

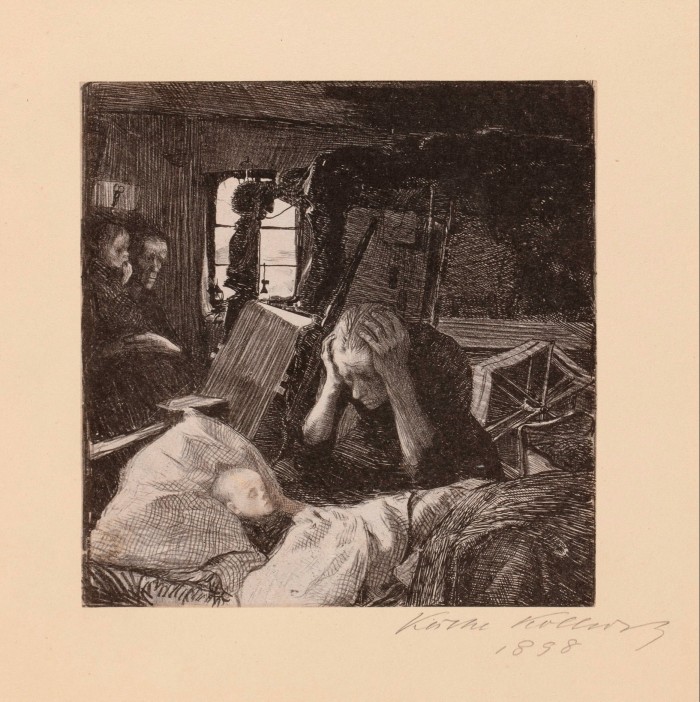

The series opens with “Need”. A woman in black hunches over a young boy so obviously sick that his features seem to be erasing themselves. She buries her head in fleshy, oversized hands; there’s nothing else for them to do. In one dim corner, a man hugs another sunken-eyed child, but the house hardly has room for sorrow. A loom and a spinning wheel hog the background, waiting for work to return. In subsequent scenes, collective action crowds out individual suffering: workers plot, storm the employer’s gates and, inevitably, lie dead in pools of darkness.

In 1898, the jury at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition nominated the series for a gold medal, but Kaiser Wilhelm II himself vetoed the honour. “A medal for a woman, that would be going too far,” he harrumphed. “Distinctions and medals belong on the breasts of deserving men.” Then, as now, a rescinded prize guaranteed attention, and suddenly Kollwitz had a persona to live up to.

Once again, she turned to the past to explain the present. In “Peasants’ War”, a brilliant seven-part suite of prints that came out in 1908, she illustrated the 1524-25 uprising that German leftists saw as a glorious episode in an ongoing revolution. Kollwitz, evidently not so sure about the glory part, treated both tyrants and freedom fighters as actors in crazed spasms of violence.

“Raped” is a scene of cruelty as Goya might have reported it: a semi-clothed woman’s body abandoned by the resident landowner in the backwoods of his estate. We see her foreshortened, splayed, her face obscured, already merging with the landscape. Other plates cut to the vengeful peasants. In one, a woman grips a scythe in one huge fist, resting the blade against her own cheek, honing schemes of slaughter.

Kollwitz appreciated the planned, deliberate outburst — it’s how she worked, too. MoMA lines up some of the many versions of the lady with the scythe, and we watch it become more concentrated and purified in each iteration. She edits out a man leaning over from behind to guide the whetstone, zooms in on the woman’s torso, then crops the image yet again, deepens shadows, gnarls knuckles and bulges veins, until you can feel the fury rising from her skin.

“Charge” features the peasants’ legendary leader, Black Anna, another aged embodiment of female wrath. We see her from the back, stooped and ancient but erupting with energy as she goads the mob to rampage. Her hands tell the story: sinewy and strong, they contort wildly, euphorically, demanding an orgy of retribution.

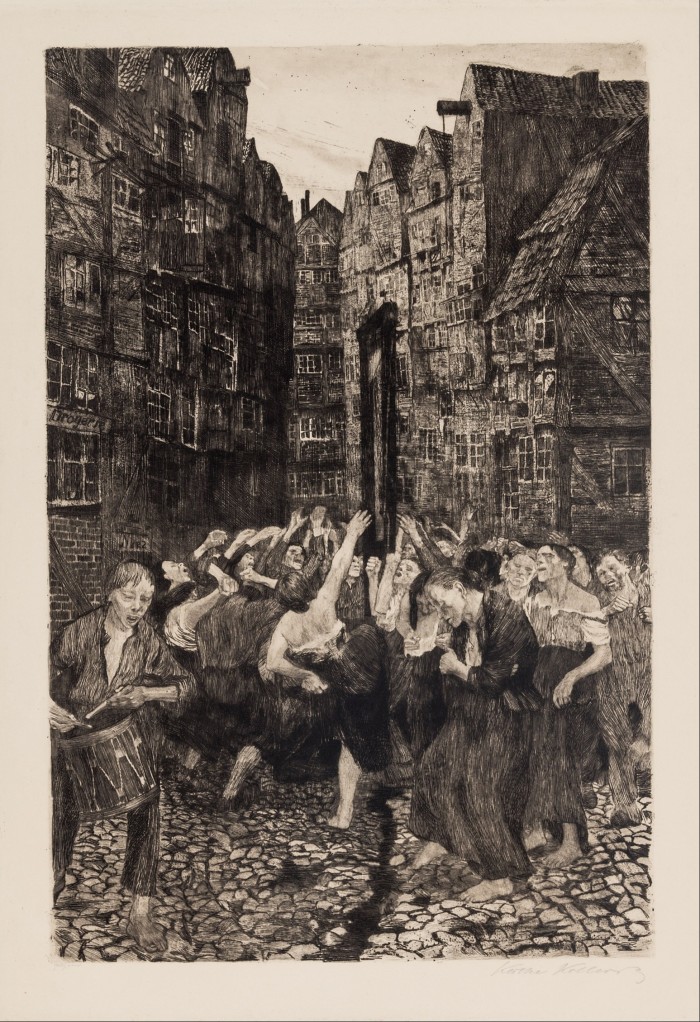

A related print, “The Carmagnole” (1901), was inspired by Dickens’s description in A Tale of Two Cities of hordes cavorting around the guillotine: “No fight could have been half so terrible as this dance . . . a healthy pastime changed into a means of angering the blood, bewildering the senses and steeling the heart.”

With Dickens as her guide, Kollwitz’s sympathy for the victims of oppression shaded into outrage at their savagery. Dipping into caricature, Kollwitz populated her scenes less with individual sufferers than with ugly, lowdown types bent on destruction. She never forswore the socialist struggle but, a few years later, abandoned her allegiance to the cleansing power of force.

Her solidarity came bundled with empathy and a measure of distance. She was not a prole, but a middle-class believer, the daughter of a lawyer who gave up the profession to work with his hands alongside men who had no choice. She, too, surrounded herself with members of a class that was not her own.

“It was only when I became acquainted with the women, who came to my husband seeking aid and incidentally also came to me, did I truly grasp, in all its power, the fate of the proletariat,” she recalled. The social misery she saw troubled her, and also furnished her material. Even in her most inflamed images, she was telling someone else’s story.

But not for long. Kollwitz’s shell of privilege dissolved in stages. Her 16-year-old son Hans contracted diphtheria in 1908; he survived, but the ordeal of uncertainty worked its way into the etching “Death, Woman and Child”. A mother with the artist’s face holds fast to her son’s feeble body while a skeletal arm reaches into the frame and wraps itself around the boy, pulling him away.

War broke out six years later and her younger son Peter, not yet of age, requested his parents’ permission to enlist. Karl refused but Käthe agreed. Her assent was all he needed. Two months later, Peter was killed. She slid into a bog of depression and self-blame, emerging a fully-fledged pacifist and an expert on grief.

“I have been through a revolution, and I am convinced that I am no revolutionist,” she wrote. “My childhood dream of dying on the barricades will hardly be fulfilled, because I should hardly mount a barricade now that I know what they are like in reality.” Her subject matter didn’t change, but the emphasis did. A set of woodcuts from the early 1920s, “War”, concentrates on grieving wives, mothers, and children.

The Weimar years brought temporary respite and respect. Kollwitz was the first woman to be elected to Berlin’s Prussian Academy of Arts. Then the Nazis came to power, forced her to resign her post, stifled her ability to exhibit and threatened to ship her to a concentration camp. In the mid-1930s, she channelled this latest round of horrors into the late, magnificently gloomy “Death” cycle, which proved unbearably prescient. Her husband died in 1940, and two years later her grandson was killed on the eastern front. She didn’t quite live to see the war end, but died a few days before her ruined country surrendered.

If anyone has ever understood what it means to die, she did. Death appears as a bony figure, alternately fearsome and seductive. The final print in the series is a self-portrait, done in 1937. Long fingers of mortality tap her on the shoulder and, though the artist looks gaunt and hollow-eyed, she also seems unfazed, raising her own hand as if to complete a thought. One more gentle nudge, perhaps a tap on a watch face, and she will get up from the table, ready to meet the terror she had always known.

To July 20, moma.org

Comments