Francis Bacon at Monaco’s Grimaldi Forum

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Sometime between 1948 and 1950, Francis Bacon won £1,600 at the casino in Monaco and splashed it all on renting a villa there. The Côte d’Azur, Somerset Maugham’s “sunny place for shady people”, was perfect for Bacon.

“Nobody here is at all interested in ART, which is perhaps a comfort,” he wrote to Graham Sutherland. On the other hand, gambling “is for me intimately linked with painting” — the studio and the gaming tables shared dramas of chance, accident, risk — and “I love being on this coast, with this light, one always seems to be on the edge of the real mystery”. He kept revisiting the principality for the rest of his life.

Francis Bacon, Monaco and French Culture, the summer exhibition at Monte Carlo’s Grimaldi Forum, is pure pleasure: visual, emotional, intellectual. In this glassy seafront gallery, Bacon’s art of sensation and excess is staged in an extravagant mise-en-scène of purple velvet curtains, red carpets and, at the centre, an enormous black room with light filtering through blinds, reminiscent of the shuttering device in the dark early canvases.

In this cavernous installation, you feel dizzyingly as if you are walking into an airless 1940s Bacon painting. Ghostly striated renderings from 1949 here include “Figure Crouching”, an abject form in a space frame leaking a greenish shadow, never shown before; a little-known snarling “Head”, compressed by tight collar and tie and confined in a cage; and the famous “Head VI”, a screaming Pope with phallic gold tassel mockingly swinging above his nose — Bacon’s first composition to converge imagery from Velázquez’s “Portrait of Pope Innocent X” with a still of the howling nurse from Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin.

“It is thrilling to paint from a picture which really excites you,” Bacon told Sutherland. It was in 1949 that, at 40, he really found his subject of a figure isolated in a room or constrained abstract space. “I do absolutely understand what Giacometti meant when he said ‘why ever change the subject?’” he said. “Because you could go for the whole of your life painting the same subject.”

Nevertheless, variety early on, and the references to Monaco and to French painting as explored here, are revelatory. The unstable forms against a Mediterranean blue ground in “Figure with a Monkey” (1951), where both the chimpanzee and the human spectator, manacled in white collar and cuffs, seem imprisoned by a chain fence separating them, was inspired by endocrinologist Serge Voronoff’s experiments with monkeys at the Chateau Grimaldi. “Study of a Dog” (1952) swirls menacingly within a giant roulette wheel set on Monaco’s coastal road with a single palm tree; an azure line denotes the Mediterranean.

That line reappears in “Fragment of a Crucifixion” (1950): two bloodied falling forms, sourced from a photograph of a barn owl carrying its prey, are placed on a canvas left half-unpainted. On this raw surface, small abbreviated walking figures recall the calligraphic taches of Henri Michaux — a pen and ink sketch similar to one Bacon owned is on display — and cars purr through the heat: death amid banal, quotidian reality.

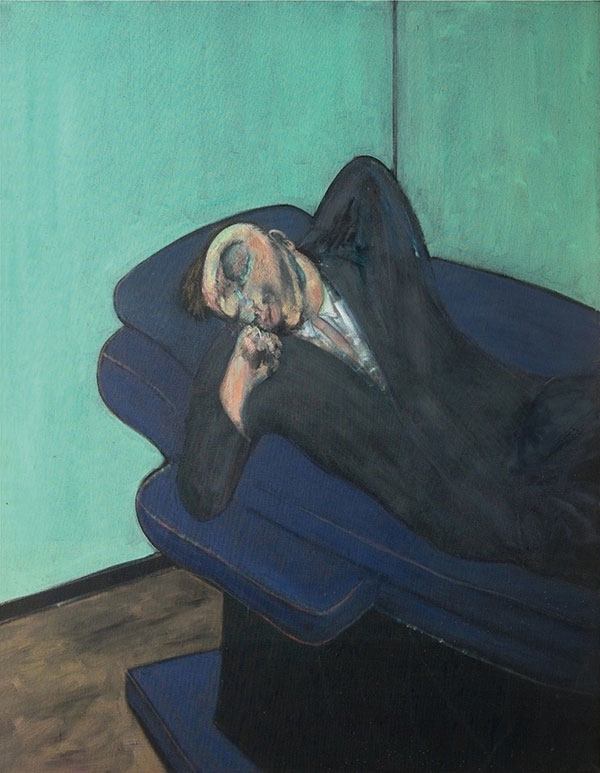

Emerging from the black box of these early works, you enter a brilliant display of the deformed 1960s-80s portraits on shrill coloured grounds: bright yellow for three distorted heads of Henrietta Moraes, shocking pink overwhelming a curled up John Edwards.

The highlights are the paintings composed for Bacon’s 1971 retrospective at the Grand Palais (“Paris is the supreme test”) including “Lying Figure in a Mirror”, an androgynous twisted form evoking Michelangelo’s “Leda and the Swan”, and the gender-bending lilac “Triptych — Studies of the Human Body”, where Bacon contorts and isolates figures derived from a Picasso nude, the Belvedere Torso — the absent head concealed by a black umbrella, another shadow of death — and Caravaggio’s “Narcissus”.

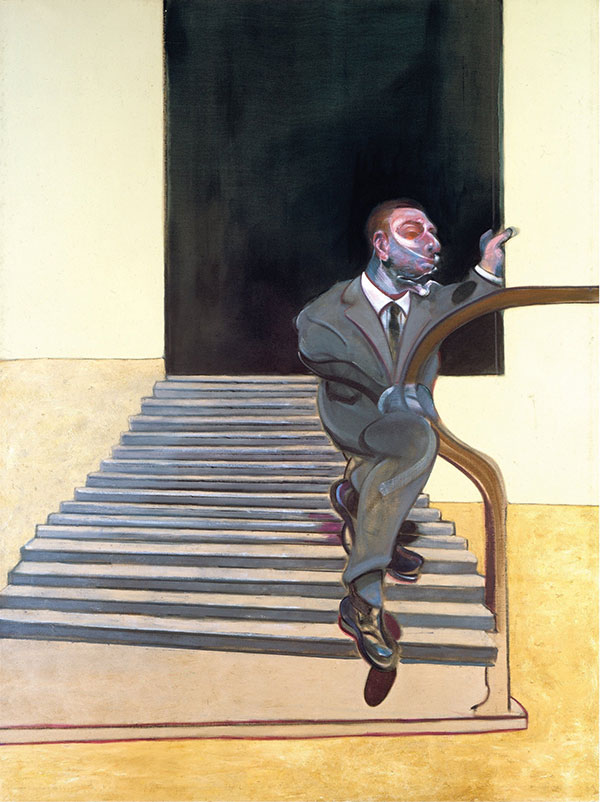

“Portrait of a Man Walking Down the Steps” (1972), unseen for 40 years, depicts Bacon’s lover George Dyer, tentatively holding a blackened window frame as blood drips beneath him on a staircase resembling that of the Hotel des Saint-Pères, where Dyer committed suicide on the eve of the retrospective.

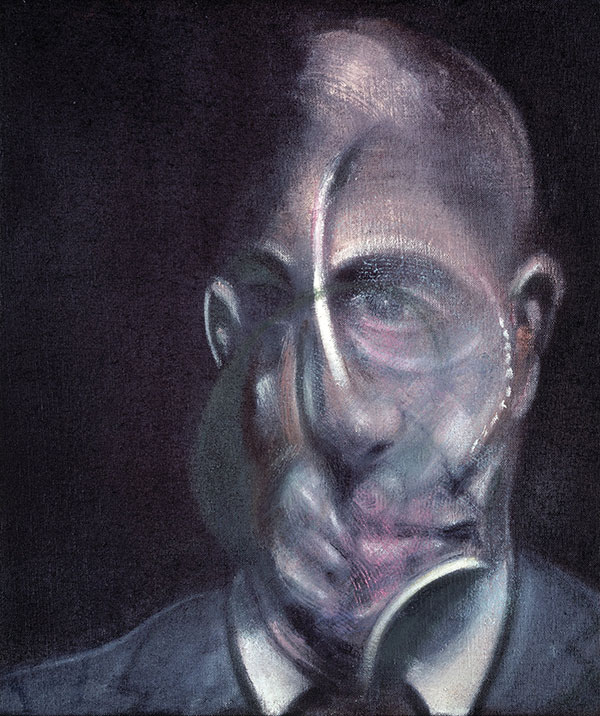

It is among many later rarities: “Study for Self-Portrait” (1980) in a pale, diffused blue reminiscent of Degas’ pastels (“there, this is my Impressionist period”), comes here from a private collection for the first time; “Study of a Bull” (1991), a monochrome of a magisterial, threatened beast receding through a white mirror, on a canvas sprinkled with aerosol paint and dust, is Bacon’s last painting and has never been exhibited before.

Such trophies keep the show startling until the end. Although not all have direct French connections, the École de Paris context, with Giacometti, Soutine and Picasso, favoured by Bacon for “un sens très fort de la tragedie” also on display, resoundingly positions Bacon as the last great European modernist.

Benefiting from years of research unearthing paintings across four continents, Monaco’s exhibition is curated by Martin Harrison, whose definitive five-volume catalogue raisonné (The Estate of Francis Bacon £1,000) appeared last month. The most significant work of 20th-century art history this decade, it is also lively, engaging and, in a defiantly biographical approach, illuminates works with gossip and anecdote, as well as with iconographic and literary reference.

It features 100 previously unpublished and unseen paintings, ranging from “Landscape with Pope/Dictator” (1946), in which Bacon sets an early version of his recurring motif against a classical colonnade and decorative purple flowers, to “Self-portrait with Injured Eye” (1972), painted after Bacon “suffered many beatings, which as a masochist he may not have found entirely uncongenial . . . the injured eye . . . stands as an autobiographical symbol”.

There are fewer homosexual couplings (11) than one imagined, more female nudes (18), and an unexpected menagerie of animals alive, dead and ornamental. Bulls, gorillas and dogs predominate, plus a camel with a thrown rider in “Unseated Picador”; “Chicken”, modelled from a Conran cookbook illustration but recalling Soutine in blood-smudged pathos, on display in Monaco; an idiosyncratic ceramic cat, worked up from a photo of a London cat’s-meat seller, in a malevolent, unique double portrait of Dyer and Lucian Freud.

“Flesh and meat are life,” Bacon said in his final interview. And “I’m like an albatross: I take in thousands of images like fish, then I spit them out on the canvas.” Harrison, in book and exhibition alike, eloquently enhances our understanding of the process, by which Bacon sustained 20th-century figuration with paintings “that can carry over from the sensation to our nervous system”, and continue to disturb and astonish.

Grimaldi Forum, Monaco, to September 4. grimaldiforum.com; ‘Francis Bacon: Catalogue Raisonné’ is published by The Estate of Francis Bacon

Photographs: Estate of Francis Bacon/Ordovas; Estate of Francis Bacon/Kunstmuseum; Estate of Francis Bacon; Estate of Francis Bacon/Musée national d’art/Centre de création industrielle; Estate of Francis Bacon/Arts Council Collection

Comments