Tata: Boardroom divide in Mumbai

Simply sign up to the Indian business & finance myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

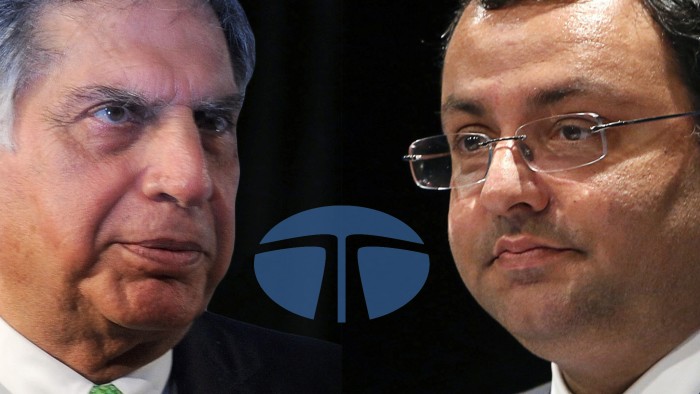

Less than a month before they forced the dismissal of Cyrus Mistry from the helm of India’s Tata conglomerate, a searing memo circulated among the trustees of the Tata Trusts, the group’s dominant shareholder.

The document, handwritten by 81-year-old trustee NA Soonawala, gives a powerful insight into mounting unhappiness in the inner circle of Ratan Tata, the patriarch who returned on Monday as chairman of the group’s holding company Tata Sons.

Mr Soonawala, who served as Mr Tata’s vice-chairman for a decade, warned of a deteriorating situation at three “major problem companies” — Tata Steel Europe, Tata Teleservices and Tata Motors’ Indian operations, which he said were facing huge losses and declining market share.

His memo — a copy of which was obtained by the Financial Times — lambasted a lack of relevant experience among the members of Mr Mistry’s senior team. It also accused Mr Mistry and his colleagues of using the media to exaggerate problems they inherited from Mr Tata’s 21-year tenure.

“One wonders why the eminent board of the parent company, Tata Sons, and its majority shareholders are seemingly sitting back and letting things ride,” Mr Soonawala wrote, urging them “to protect their financial interests and the values associated with the Tata name”.

Mr Soonawala’s desire for action was soon satisfied. On Monday the Tata Sons board voted to remove Mr Mistry from the chairmanship, sparking a vicious war of words that has raised speculation of a possible legal fight.

This week’s dramatic events have thrown into question the leadership of India’s largest business group with more than $100bn in annual sales and businesses, ranging from the country’s leading IT services company to the UK’s Jaguar Land Rover carmaker.

“There was a feeling that Cyrus was taking very small incremental steps,” says Prabodh Agarwal, president of IIFL Holdings, a financial group. “But this is an extraordinary event. Nobody could have predicted this.”

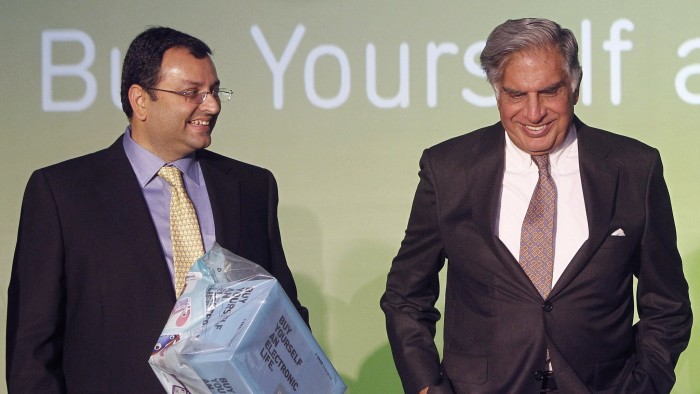

The scion of a family that controls 18 per cent of Tata Sons shares, connected to the Tata clan through his sister’s marriage, Mr Mistry became the first chairman drawn from outside the founding family in its 148-year history when he took charge in December 2012. He had been bolstered by a ringing endorsement from his predecessor, who promised to give him “space” to run the group.

The old guard became alarmed within just a few months, as Mr Mistry assembled his “group executive council” — five advisers who were younger than the industrial veterans that had surrounded Mr Tata.

Two of the team were longstanding group employees, but senior figures at Tata Trusts and on the Tata Sons board grew worried about the experience of the three outsiders, a former management consultant, an ex-banker and a professor at the London Business School, according to two people with knowledge of the concerns. “The biggest thing against Cyrus was that he never had a strategy beyond what these business school people gave,” says one person who was briefed on the growing concerns. “That basically ruined him.”

In his angry email to the Tata Sons board on Tuesday, Mr Mistry dismissed the idea that he lacked a strategy, pointing to the “Vision 2025” framework he unveiled in July 2014. That strategy sought to align objectives with targets based on the number 25: by 2025 Tata would seek to reach 25 per cent of the world’s population, to be one of the 25 most admired global brands, and to become one of the 25 most valuable groups by market capitalisation.

These “nice-sounding phrases” came “with no indications on how these ambitious targets are to be achieved”, Mr Soonawala said in his memo. The claim was disputed by people who noted detailed strategy documents presented to Tata Sons’ board, one of which has been seen by the FT.

Deterioration in relations

Concerns about a lack of strategic direction mounted as margins and market share eroded at key businesses. Mr Mistry defended his record in this week’s letter, noting that operating cash flows had grown strongly during his tenure and that the group’s market capitalisation had outperformed the BSE’s Sensex index . But his critics focused on the fact that it had become dangerously reliant on a single unit: Tata Consultancy Services, the largest of India’s successful IT services groups.

According to S&P Capital IQ, aggregate net profit at Tata group’s listed companies was 21 per cent higher in the financial year ending this March than during Mr Tata’s final year in charge, four years before. But 69 per cent of earnings for the period came from TCS, and net profit for the other companies fell 42 per cent over the same period.

In a December 2015 letter to Mr Mistry, Mr Soonawala raised concerns that profit margins for the group had shown a sharp deterioration, if the contributions from TCS and Jaguar Land Rover were excluded.

Mr Mistry responded with a presentation covering about 100 pages showing signs of improving performance in granular detail.

The pressure from Mr Tata’s camp added to Mr Mistry’s concerns about persistent undermining of his authority. The relationship further deteriorated with a series of sharp disagreements in recent months.

The first of these concerned an attempt to roll back Mr Tata’s boldest move as chairman: Tata Steel’s 2007 acquisition of Anglo-Dutch group Corus for $13bn. After a slump in steel prices left the UK division losing £1m a day, Mr Mistry oversaw the decision in March to close the business. “Most people were telling Cyrus to get out much earlier, and he persevered because he really believed he could turn things around,” says a person close to Mr Mistry.

But the decision rankled Mr Tata, who saw it as reflecting a “short-termist” philosophy tilted towards unnecessary asset sales and writedowns instead of investing and turning around struggling businesses, according to two people with knowledge of his thinking.

These people used a similar logic to dismiss Mr Mistry’s claim this week that the group faces potential asset writedowns of up to $18bn, although the warning was taken seriously by investors, who sent the share prices of several group companies sharply lower.

In fact, an identical warning had been presented to the Tata Sons board in a confidential annual strategy document, seen by the FT, in April 2015 — although much of the $18bn has now been written down, according to a person with direct knowledge of Mr Mistry’s calculations.

A further spike in tensions came in May, when Mr Tata learned of Tata Power’s plans to make a $1.4bn acquisition by reading about it in the newspaper. Tata Power, chaired by Mr Mistry, had not informed the Tata Sons board of its plans, and did so only on May 31.

In an email, Mr Tata accused the company of a “breach” of its responsibilities to the group holding company. Mr Mistry dismissed this interpretation in a statement on Friday, where he said the Tata Sons board was “adequately informed” before the transaction was completed.

One of the final blows to Mr Tata’s confidence in his successor stemmed from a dispute with NTT DoCoMo, the Japanese mobile phone operator, which accused Tata Sons of trying to escape a commitment to buy out its stake in Tata Teleservices for $1.2bn.

Tata Sons protested that it had been denied permission to make the payment by India’s central bank, and Mr Mistry’s top team were eager to pay up and put the dispute behind them, according to two people with direct knowledge of their discussions.

But Mr Tata grew unhappy with the situation. In a July letter to Ryuji Yamada, NTT DoCoMo’s former chief executive, Mr Tata wrote of his regret that their joint investment had “degenerated” into conflict, adding that this would not have happened had they both still been in charge of their groups.

By the time Tata Sons’ directors assembled for a regular board meeting at its Mumbai headquarters on Monday, they were braced for the chairman’s dismissal. So was Mr Mistry, having spoken minutes before the meeting to Mr Tata, who invited him to leave quietly, according to two people with knowledge of the encounter.

“He said: ‘Look, both of us know it’s not working, and if it’s in the best interests of the organisation, you should consider stepping down,’” says a person familiar with Mr Tata’s version of events.

But Mr Mistry instead chose to condemn his dismissal as illegal — an argument that rests largely on the argument that Tata Sons’ articles of association require him to be given 15 days’ notice of the motion to dismiss him, according to a person with knowledge of his position.

The group denies this interpretation. The articles state that any motion must be heard at a board meeting if a director gives 15 days’ notice, but do not explicitly say motions cannot be heard without such notice.

Tata Sons has already appointed a committee to find a new permanent chairman within four months. But some senior figures in Mumbai’s business world warn that it may struggle to attract top-drawer candidates after the chaotic nature of Mr Mistry’s departure.

“How this was done was completely unbelievable,” says one. “The mind of the next chairman will be drawn from managing the group companies to managing the board — and surviving.”

Additional reporting by Amy Kazmin in New Delhi and David Keohane in Mumbai

Comments