Ukraine’s urgent need for supplies lays bare Europe’s defence industry

Simply sign up to the Aerospace & Defence myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The UK’s war effort for Ukraine has its frontline on the site of a former Dunlop tyre factory in the north-east of England.

Here, at BAE Systems’ plant in Washington, workers are manufacturing hundreds of 155mm artillery shells for the Ministry of Defence. The British government, along with other Nato allies, has been sending thousands of rounds from national stockpiles to Ukraine to help its armed forces in their fight against Russia.

More than 16 months after Russia’s invasion, the artillery rounds have become the workhorse ammunition of the war and emblematic of the efforts of Europe’s defence industry to expand production of everything from munitions to tanks to meet the demands of their governments.

“‘I have seen this site go through Afghanistan and Iraq, and now Ukraine,” said Lee Smurthwaite, programme director for munitions at BAE Systems. “The site is as busy as it’s ever been and it’s going to be a lot busier.”

Ammunition crunch

This rush is mirrored across the continent as factories have stepped up output to replenish national stockpiles that are running low. EU foreign and defence ministers in March agreed an ambitious target to supply 1mn rounds of ammunition to Ukraine within a year.

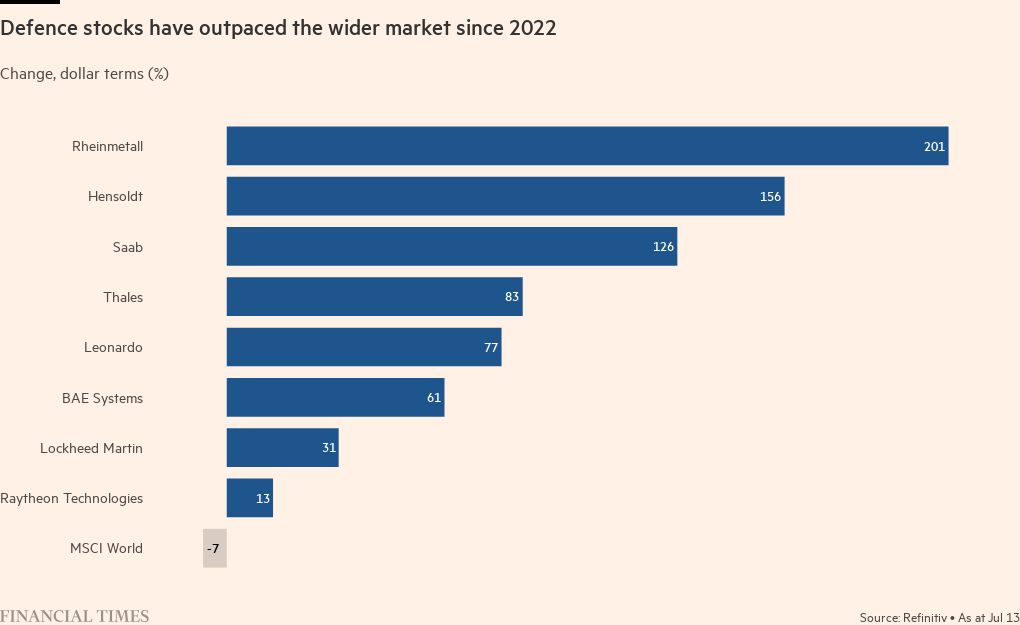

In Germany, defence manufacturer Rheinmetall is already working on new production lines and received a munitions order worth up to €4bn from the German government this week. BAE, meanwhile, secured a £190mn order from the UK to help it increase output of the 155mm-diameter rounds, although the company had already upped investment in its munitions production ahead of time. “We just got on with it,” said Smurthwaite.

A new previously planned machining line at Washington will now be dedicated solely to making 155mm shells. The site makes the shells for the rounds which are then filled with explosive at BAE’s site in Glascoed, south Wales. BAE does not supply Ukraine directly but has a long-term partnership with the Ministry of Defence that underpins production.

More orders are now being placed, but it has taken time to get here.

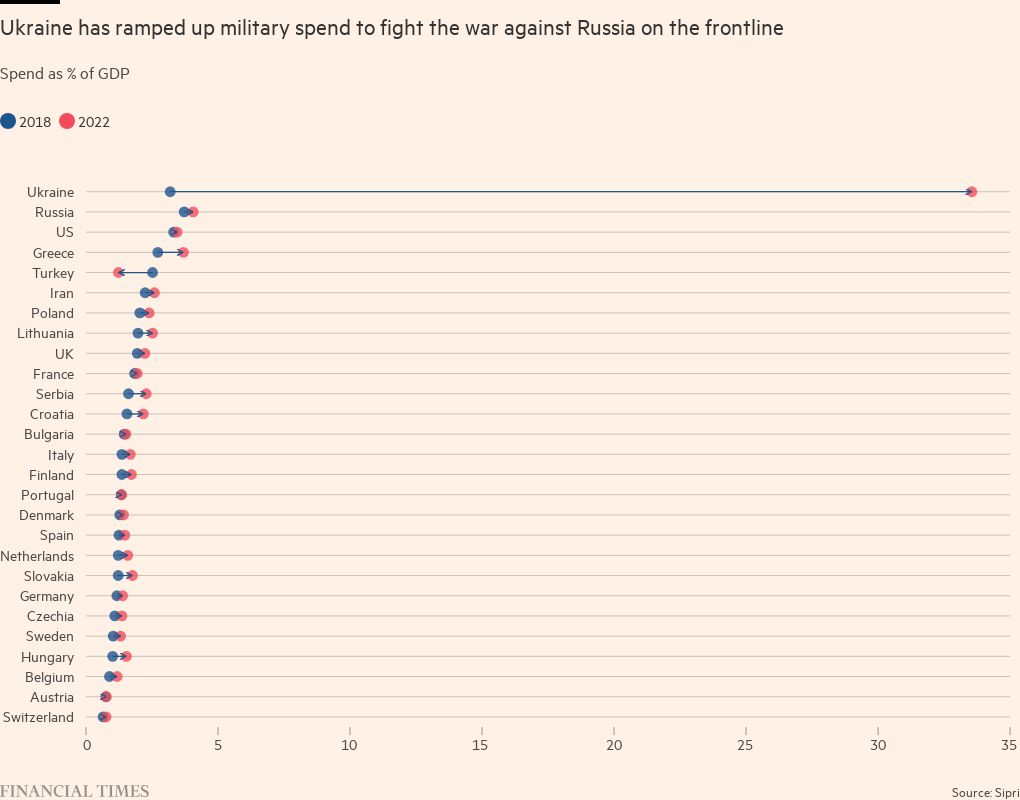

Industry executives say that despite national pledges to increase defence spending — it hit an all-time high of $2.24tn globally last year — and new procurement initiatives by both Nato and the EU, progress has been slow.

European industry is “more or less still facing the same challenges and roadblocks” some 16 months since the war started, according to Jan Pie, secretary-general of regional trade body ASD.

While the situation is very urgent in Ukraine, European countries are “still operating by peacetime processes”, he said.

Efforts to move production lines to a war footing have also been frustrated by supply chain problems and fragmented policymaking.

Micael Johannsson, chief executive of Swedish defence group Saab, said the industry needed to co-operate more closely on supply lines to reduce bottlenecks. Companies should work together to figure out “how do we prioritise, can we schedule it, can we co-invest” and to help inform governments about bottlenecks and where to prioritise investment, he told the Financial Times last month.

Alex Cresswell, UK chief executive of French defence group Thales told an industry conference last month that governments should move away from a generic weapons “stockpiling” and focus instead on “genuine sharing [of] supply chains”.

Susanne Wiegand, chief executive of Germany’s Renk, which makes transmissions for tanks, including the Leopard 2, said the industry needed “more planning certainty from policymakers”. Renk, she added, was in favour of a permanent government and industry task force that would work together on speeding up procurement and delivery.

National rivalries

The ammunition crunch is driving much of the current debate about resilience but there will be demands for new weapons in the longer term.

Ukraine’s armed forces will need to be rebuilt after the war, while Nato has already indicated that it wants to increase its high-readiness forces. All of this implies more weapons and more investment.

Yet pan-Europe defence collaboration faces significant hurdles. The EU has been trying to develop the bloc’s capacity for independent military action and strategic autonomy since the launch of its common security and defence policy in the late 1990s. Defence spending, however, is still controlled by each member state, while national rivalries continue to dominate, undermining joint procurement initiatives.

One European defence official said: “When we say in Brussels to each other that we . . . [want] better co-operation . . . nations are still promoting and procuring their own stuff.”

“There was no real European co-operation in times of austerity, when the defence industry was small and everyone said they had to protect national autonomy,” commented an executive at a German defence group.

“Now we have the opposite situation, where there’s a lot of money but everyone’s saying let’s keep the money in the country and not give it to others — even if they’re allies. It didn’t work in bad times and it doesn’t look like it’ll work in good times.”

Michael Schoellhorn, chief executive of Airbus Defence and Space, said that there needed to be more collaboration across Europe, adding that new money coming into the sector because of the Ukraine war had fuelled a tendency to focus on national champions.

Although Airbus is benefiting from the higher spending, “we have to concede that the European card that we play is currently not resonating so much with our home countries right now”.

There are also concerns that procurement decisions in favour of the US will undermine any European plans to bolster its industrial base.

“What I’m asking for is balance,” said Schoellhorn. “If there is a need to buy off the shelf because it’s a crunch need, and that’s the only thing available and it works, fine.”

Europe needs to decide whether “we want long-term core competencies that we will develop over a long horizon”.

A Germany-led plan announced last year, dubbed the European Sky Shield initiative, to buy Patriot missile systems from the US, Iris-T missiles from Germany and the Arrow from Israel, blindsided France and excluded MBDA, a pan-Europe group that has been making a Patriot competitor.

Schoellhorn said the initiative was a “good thing in my view” given that the Ukraine war had “amplified the need to do more on air defence”. Nevertheless, he said he wished there had been “more discussion and ultimately collaboration . . . also between France and Germany”.

The Sky Shield initiative “should ideally also entail some of the capabilities that we have in Europe with MBDA and others because we can contribute”.

He added that although the importance of an industrial strategy for defence was now being recognised in Germany, the country “has had a deficiency . . . in terms of long-term strategic thinking when it comes to defence and foreign policy and security”.

Airbus is a partner of Germany’s Diehl on the Iris-T missiles. It also has a stake in MBDA.

Access to finance

For European industry, there is another significant challenge: access to finance as banks and fund managers have bought into the trend for socially responsible investing. Before the war, executives had begun to worry that the sector was in danger of becoming “uninvestable” for funds because of ethical questions around defence investment.

Although the war has changed the view of some investors, industry body ASD says more needs to be done. “If you want to see this increased production, then also you need access to private finance,” Pie said.

The association has been calling for a change in the lending policy of the European Investment Bank to encourage private investors. It also wants the European Commission to make a joint statement with the EU diplomatic service that “investment in defence is compatible with EU sustainable finance regulation”, Pie added.

After Ukraine

The war may have spurred Europe’s policymakers and companies into action but the reality is that production will take years to match the sudden jump in demand. Industry also needs to persuade governments that defence is not just an insurance policy at times of war.

When the cold war ended, the result was “shrinking defence budgets, shrinking orders and a reduction in force structure and a much smaller home market”, said Bastian Giegerich, director of defence and military analysis at the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

“That is what companies will have in mind — the threat environment had changed and EU armies turned themselves into contributors to non-essential crisis management missions around the world. It is no surprise that they are now thinking, should this war end, will we see the same thing happen?”

Comments