From Africa to Asia, political frontiers are no barrier to art flow

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Exquisite 15th-century bronze figures from the kingdom of Benin were first exhibited in Europe as high art, rather than anthropological artefacts, in 1939. According to Neil MacGregor, the director of the British Museum, the realisation that bronze of such quality was being created in Nigeria before the sculptures of Benvenuto Cellini, and at the same time as Donatello, “caused a sensation — a transformation in Europe’s understanding of Africa. It undercut all the racist assumptions that had made the colonial venture possible.”

Yet decades before that exhibition in London, Henri Matisse had spotted a wooden African head in a Parisian antique shop on his way to see the writer Gertrude Stein. Rather than pausing to debate whether the exhilarating sculpture constituted art or not, he grabbed it “for a few francs” and took it to Stein’s house, where Pablo Picasso was similarly “astonished” by it. As Matisse later wrote in 1953, “that was the beginning of the interest we have taken in Negro art and we have shown it, to a greater or lesser degree, in our own pictures”. His oil painting The Italian Woman (1916) is but one example of that influence; the development of cubism another.

Such seminal moments are a reminder that, however slow Europe may sometimes have been to accord the status of great art to the creativity of others, many artists have done so more readily, not to say rapaciously. The incessant borrowing and flow of art has never been halted by political frontiers. Art forms beyond Europe and the western world have had a stimulating, at times decisive, influence, not always acknowledged or remembered, on the development of western art and modernity.

Matisse Arabesque, a recent exhibition at the Scuderie del Quirinale in Rome, traced the far-flung inspirations behind one painter’s art. Not only did Matisse marvel at west and central African sculpture, but in Notes of a Painter on His Drawing (1939), he acknowledged the “arts of the Orient”, after the great masters in the Louvre, as decisive in his artistic education. Other stimuli ranged from sojourns in Algeria and Morocco and an exhibition of “Mohammedan” art in Munich in 1910, to Chinese painting, Japanese woodcuts and the jade-green of Korean chongja glaze.

“Not knowing ourselves too well yet,” Matisse later recalled of his youth, “We felt no need to protect ourselves from foreign influences, for they could only enrich us and make us more demanding of our own means of expression.” As he also realised, “I am made of everything I have seen.”

Visual art from Latin America and the Caribbean has as surely had an impact beyond the region. Rather as Matisse developed his palette through contact with north African and eastern arts, Impressionism had a founding father in Camille Pissarro, who brought to 19th-century Paris the tropical light of his Caribbean upbringing. Diego Rivera, a founder of the post-revolutionary Mexican muralist movement of the 1920s, alongside David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco, combined the techniques of the European masters and Italian Renaissance fresco painting with the aesthetics of pre-Columbian civilisations, whose art he amassed in his private collection. His murals in the US, often on public buildings, not only reinvigorated the mural as an art form, but reinvented public art, arguably paving the way for the Federal Art Project of the Depression-era 1930s.

FT Special Report

Contemporary art from the continent has the lure of the new, but African economies’ double-digit growth is also driving the market

Read more

Writers, too, are made of everything they have seen — and read. If Don Quixote was the first modern European novel, then its origins owe much to the Arabic epics that Miguel de Cervantes knew well and which filled the libraries of Andalucía. The tales of Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron are similarly beholden to the Thousand and One Nights. While later European writers have celebrated these sources, from Federico García Lorca to Juan Goytisolo, the Arab contribution to European literature tends to be forgotten. When the 1988 Nobel Prize in literature was awarded to the Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz, the sole Arab recipient to date, the Palestinian-American critic Edward Said wrote that “of all the major literatures and languages, Arabic is by far the least known and the most grudgingly regarded by Europeans and Americans”.

The influence of Asian literatures and philosophies on European and American modernist literature is, conversely, well documented, from Ezra Pound’s Cathay sequence interpreting Chinese poetry and TS Eliot’s debt to the Bhagavad Gita in Four Quartets, to WB Yeats’s admiration for Rabindranath Tagore, the Bengali poet and 1913 Nobel laureate. Long before Salman Rushdie and Vikram Seth, Indian writers were championed by western contemporaries: EM Forster wrote a preface for Mulk Raj Anand’s 1935 novel Untouchable; TS Eliot praised GV Desani, whose 1948 novel All About H Hatterr, with its revolutionary “rigmarole English”, was in turn an influence on Rushdie.

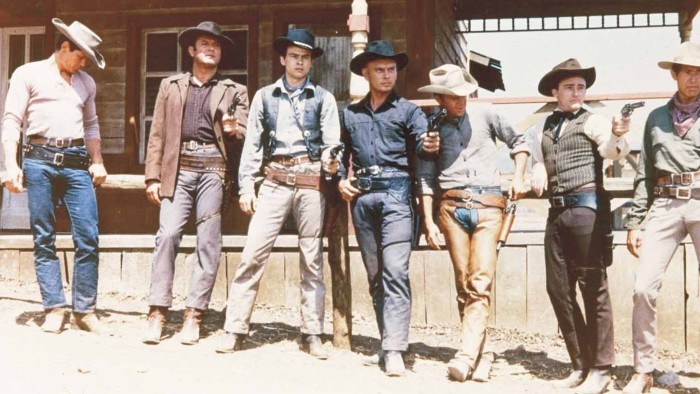

The pioneering development of cinema in Europe and the US might seem immune to seminal input from the rest of the world. Yet two of the “four greats” named by the director Martin Scorsese are Asian auteurs: Satyajit Ray and Akira Kurosawa (the others being Ingmar Bergman and Federico Fellini). The Sicilian-American Scorsese saw his first Ray film, Pather Panchali (1955), one Sunday night in New York in the 1950s and never forgot his introduction to Indian culture and Bengali cinema. More recently, Wes Anderson dedicated his fifth feature, The Darjeeling Limited, (2007) to Ray. As for Akira Kurosawa, his 1954 film Seven Samurai was reincarnated six years later as John Sturges’s The Magnificent Seven. The Japanese tale of a group of peasant rice farmers terrorised by bandits later had a discernible influence on George Lucas’s Star Wars.

Günter Grass, the German Nobel laureate who died earlier this year, once told me that Kurosawa’s film Rashomon (1950), winner of the Golden Lion at the Venice film festival, was an inspiration for his most famous novel The Tin Drum (1959), along with Rabelais, Grimms’ fairytales and (back to Cervantes) the Spanish-Arab picaresque, in whose character of the picaro “the era is reflected in concave and distorting mirrors”. Yet it was to the Japanese filmmaker’s medieval mystery, told from varied perspectives, that Grass confessed he owed his greatest insight, that “there is no such thing as The Truth”.

Maya Jaggi is an award-winning cultural journalist and critic who has profiled many global writers and artists, and been a judge of international awards including the Man Asian and Dublin Impac literary prizes.

Comments