Who’ll buy the Treasuries? (Alphaville’s version)

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The US has been selling a whole lot of debt lately.

The Treasury Department expects to sell $962bn in Treasuries in the first half of this year, according to the latest quarterly borrowing estimates. That’s not unusual, at least by recent standards, as first-half issuance totalled $1.3tn last year. And neither sum comes close to the $3.2tn of Treasuries sold to finance Covid-19 relief in the first half of 2020.

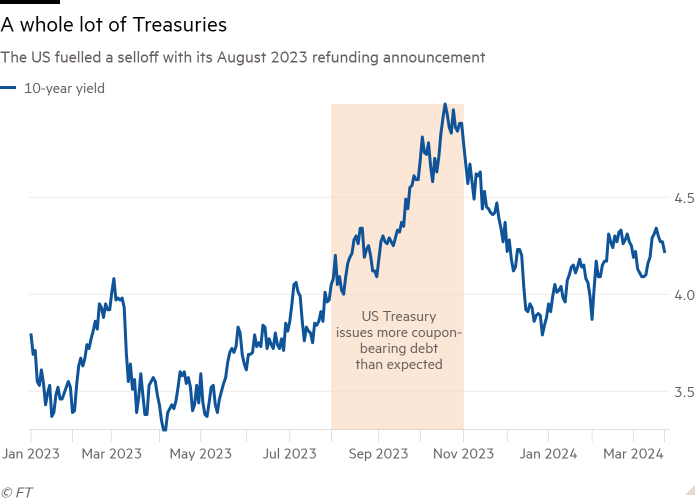

Still, the size of this year’s Treasury auctions clearly does matter: A punishing sell-off in long-dated Treasuries only abated after US officials announced a timeline for a slower flood of new notes and bonds in November 2023.

Now, macro markets are a big topic, so it can be tough to write about without getting too abstra —

[Enter KELLY, a fictional associate at a big-law firm]

Uh oh. What’s this about a “Liz Truss-style market shock”? What even is a Liz Truss?

Oh, uh, that’s a very long, very British story involving at least one lettuce, but it basically boils down to the Congressional Budget Office’s director saying that the US debt burden is on an “unprecedented” trajectory, which could at some point cause problems.

It took forever for me to get around to opening up a TreasuryDirect account, and now you’re telling me that this market is actually a mess?

Wait, no! Hahahaha no, no, the market is fine. I mean, it’s big, but it’s fine.

So first of all, when it comes to TreasuryDirect, you’re not alone. Regular people are buying the most Treasuries at auction on record, according to US data. And it’s almost always worth it to cut out unnecessary fees for standardised investment products like Treasuries or index funds.

As for the broader market and debt issuance . . . well, clear-eyed discussion can be difficult. That’s because macro markets — like sovereign debt and currencies — are a Rorschach test. Think debt is a mechanism of global oppression? There are multiple books for that. Dislike government spending and public goods? Many elected officials and high-profile executives argue there are simply too many Treasuries.

But FedSoc says — I mean, uh $962bn is a big number.

It is, though the US economy and the Treasury market are both so big that it’s kind of difficult to wrap your head around. This isn’t a corporate or municipal borrower we’re talking about.

Like do we measure annual US borrowing against economic output? If so, that leaves us with a projected deficit that’s more than 6 per cent of GDP. Remember, measuring total outstanding debt against GDP is a little weird, because it’s comparing a stock (debt) to a flow (GDP). If we do, though, total debt is more than 120 per cent of GDP.

Still, do we compare our outstanding debt levels to Japan’s, or Europe’s, or to another place entirely? The US is a giant country with a massive economy, so it makes sense that the number would be big. What value do we assign to the US’s role as global power, and to the dollar’s role as the predominant currency of trade? How much does that explain the debt stock?

All types of economists agree that issuing too much currency and/or debt can create inflation, and that’s a risk. Even so, inflation isn’t always driven primarily by government debt; there are plenty of external factors, like commodity supply shocks and corporate pricing power that can cause consumer prices to rise.

And honestly, the whole debate over whether debt is inherently Good or Bad is pretty tiresome. Debt is a tool, like anything else. We all use it.

Even without getting into whether that’s good or bad . . . it’s still a little worrying right?

I mean . . . it is a big number! But what’s the consequence here? Why is the big number scary?

But how are they going to sell all of it? What if something goes wrong?

Well, what might be most striking about Treasury auctions is how heavily stage-managed the whole process is. They’re not actually allowed to fail, because primary dealers — a club of big banks — provide a backstop.

We’ve written about how policymakers have historically worked with primary dealers to stabilise trading in Treasuries. Well beyond that, primary dealers are required to bid for their pro-rata share of Treasury auctions. Today that’s 4.2 per cent for each of the 24 firms.

So if a bond auction can’t fail, how do I know the US government isn’t taking on a disastrous amount of debt? Or, uh, borrowing for the wrong reasons, to put it differently?

Ha, trust me, you’d know! The primary dealers mostly only buy on behalf of investors, and there’s a clear process to decide what they want to pay for newly issued Treasuries. If the US government really screwed up, yields would go nuts, the way they did in the UK . . .

So that was what the CBO stuff was about, that we could end up like the UK?

Well, yes, but they didn’t say it’s going to happen imminently. He just said it was possible. And remember, it’s basically his job to say that sort of thing.

Also, it’s easy for Europeans and Brits and even Americans to forget that the US is really big. Like, really really big. Our economy can absorb a lot more debt and other types of nonsense than the UK’s.

But you said the sales were stage-managed.

Yes, it is, and you could argue that’s just good governance.

The Treasury Department is heavily involved months before any sale happens, and has committed to “regular and predictable” issuance. That means that any significant changes to issuance have to be telegraphed clearly in advance.

First, officials do lots of consulting with industry groups. An important one is called the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee, which includes some of the biggest players in the market: Think global banks, Vanguard, Fidelity, hedge funds, and even a public pension fund.

The TBAC meets quarterly to discuss debt management with US officials, including stuff like the reintroduction of the US’s 20-year bond. Primary dealers also meet quarterly to discuss issuance, but their main relationship is with the New York Fed.

The most important takeaway here is that even minor changes to the Treasury’s debt-management policies aren’t a surprise. If anything, it’s rarer for an idea to move out of the perpetual-discussion stage and into a policy shift. For example, Treasury’s plan to repurchase off-the-run bonds to improve liquidity has been floating around (albeit without much signal of seriousness) for years, if not decades.

Still, what happens when the US actually has to borrow—I mean, sell all these new bonds? Can you talk me through the process?

The auctions themselves come with varying amounts of advance notice. Sales of bills, which mature in a year or less, are announced several days beforehand.

For longer-dated notes and bonds, the Treasury publishes tentative auction sizes and calendars weeks or months ahead of time, in its quarterly refunding announcements. That’s because notes and bonds are a bit riskier to buy — due to called duration risk — so they require more preparation from investors and bond dealers.

The pricing process begins before the sale, too. Many auctions are “reopenings”, or additional sales of securities that are already trading, so those notes/bonds should in theory reflect the extra supply when it’s officially announced.

And when the detailed announcements are published, primary dealers start to make markets in “when-issued” securities, which trade ahead of the actual sale and help with price discovery.

So there are a ton of guardrails.

Yep. But it’s still possible to see changes in demand, with some context about what auction statistics can and can’t tell us.

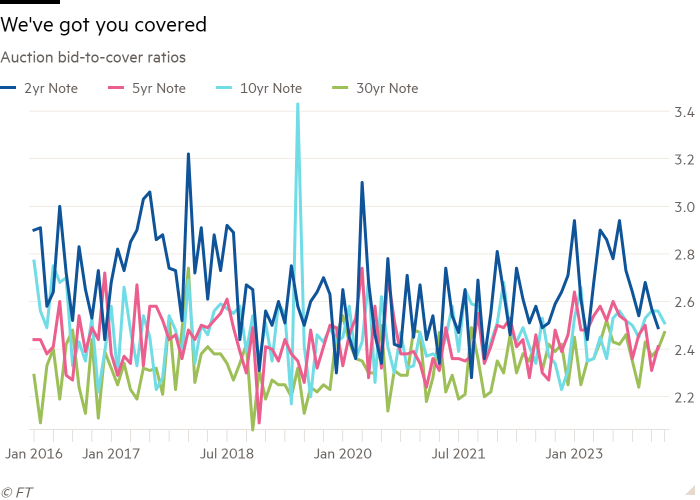

The simplest US auction stat is the bid-to-cover ratio. That’s the total dollar amount of bids entered compared to the dollar amount of Treasuries being sold.

This number is greater than 2, as a general rule, because the primary dealer provides a backstop bid and because the Treasury manages the process closely enough to be confident there’ll be enough additional demand — at whatever price — to cover the auction itself. (For example, one 2021 auction of 7-year bonds was considered exceptionally bad because its bid-to-cover ratio was 2.04.)

Anyway, bid-to-cover ratios can get a lot higher than 2:

Another measure of demand is how the final yield compares to the presale yield from when-issued markets.

Most of the trading in that market happens after the sale, but it’s still worth watching because it provides a sense of how actual demand compares to market expectations.

If a sale “stops through”, that means the yield is lower than the when-issued security. A “tail” means that the actual auction yield is higher, which can leave primary dealers with losses. If it was “on-the-screws”, that means the yield matched up with the when-issued security.

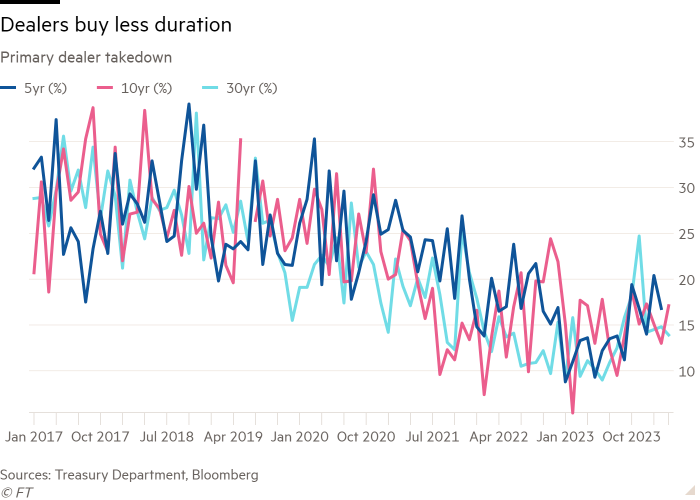

And finally, it’s seen as kind of a bad sign if a big proportion of an auction is won by the primary dealers.

That’s because they have to bid, right?

Yep! So an unusually high takedown from those 24 firms usually means that other investors were only willing to buy at prices lower than what the market (and dealers) had been expecting.

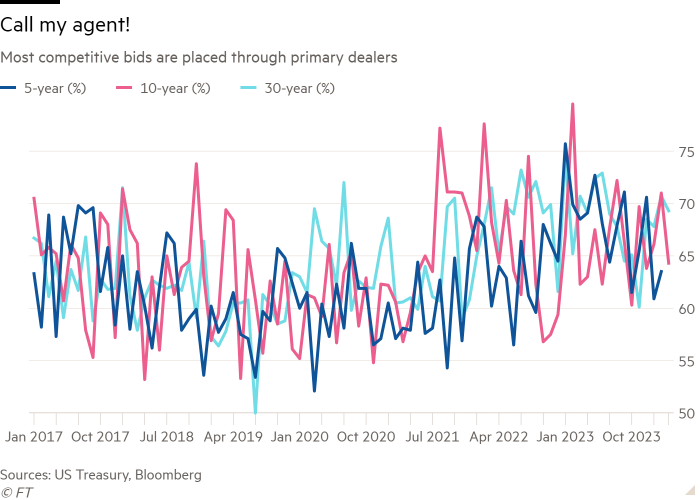

By that metric things seem like they’ve been OK lately. Primary-dealer takedown of longer-dated bonds has been pretty subdued over the past few years:

The other two competitive-bidding categories are what indicates real investor demand.

The first is indirect bidders: institutional investors who place orders through the primary dealers ahead of an auction. That’s historically been the main way (or only way) that big investors could buy, so indirect bids usually make up most of the auction takedown.

Of course, submitting your bids too early comes with some slightly elevated risk of, uh, “information leakage”. (Trading desks are run for profit, after all.) So they usually don’t bid too far ahead of the sale.

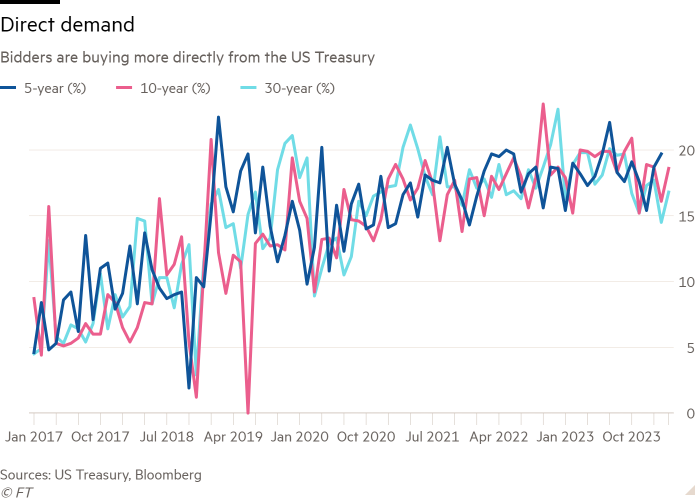

And institutions who are extra big, or extra paranoid, can also submit “direct bids” straight to the Treasury. The introduction of this was rather controversial at the time, because it disintermediates dealers and removes some of their ability to price their own bids.

OK so when it comes to the investors . . . how do we know who’s buying? Doesn’t that matter for national security?

The implications for national security can be, uh, mixed.

We’ve had many phases where various pundits worry about the amount of Treasuries owned by China or Japan or whoever, but the dollar is still the predominant currency of global trade. And that means it’s helpful for governments and companies to hold on to plenty of reserves of dollar-denominated investments.

Like . . . remember when Saudi Arabia threatened to sell all its Treasury holdings if Congress passed a bill that meant it could be held liable for the 9/11 attacks?

Yes, that’s what I mean!

So, after that, the US Treasury started breaking out Treasury ownership of individual Gulf states. The Kingdom had around $177bn, which was not even 1 per cent of the Treasuries that were outstanding at the time.

Oh. Right.

Anyway, the what-if-we-sell-Treasuries threat is the subtext of a lot of news and worries about competing currency blocs that aim to replace or provide a substitute for the dollar. And of course these types of currency blocs tend to be popular among countries trying to escape the wide net of US sanctions. But nothing’s really caught on yet.

It’s a little weird that I’m bidding for Treasuries against the Saudis, isn’t it?

Well, you might actually want to bid against them, depending on where oil prices are at the time. But no, you’re not setting prices in a Treasury auction with your bids. Together with any other normies you get grouped in the “non-competitive” category, so you end up getting whatever the “competitive bidders” determine is the price at auction.

Competitive bidders are big institutional investors that either have trading relationships with primary dealers, or access to a direct line to the Treasury Department’s auction book.

The sale itself is a “Dutch auction”, meaning the Treasury accepts bids starting at the lowest yield (highest price), and continues on to bids with lower prices/higher yields until the sale is fully allocated. The winners’ curse is avoided because the highest yield accepted is the price that every bidder gets, both competitive and non-competitive.

So I don’t really matter?

Usually, noncompetitive individual bidders are an afterthought. That’s because they’re mostly regular-ass people who use the TreasuryDirect system to buy bonds for their retirement accounts.

Not anymore, though! Turns out that higher interest rates have led to a record amounts of auction takedown and bids from individuals (since 2009 at least). That has been very helpful in absorbing all those Treasuries. But you don’t actually set the price at which the US borrows.

If we’re not determining the price, who is?

So it’s tough to tell what the breakdown looks like between different types of investors right away, because the “direct” and “indirect” bidder categories are so broad.

There was a time when market watchers tried to draw real conclusions from the shifts in indirect bids, but the direct bidding technology (called TAAPS) is available to all institutions. So the only thing you can really say about them is that they’re the type of sophisticated investor who thought it was worth the time to set up a direct line to Treasury.

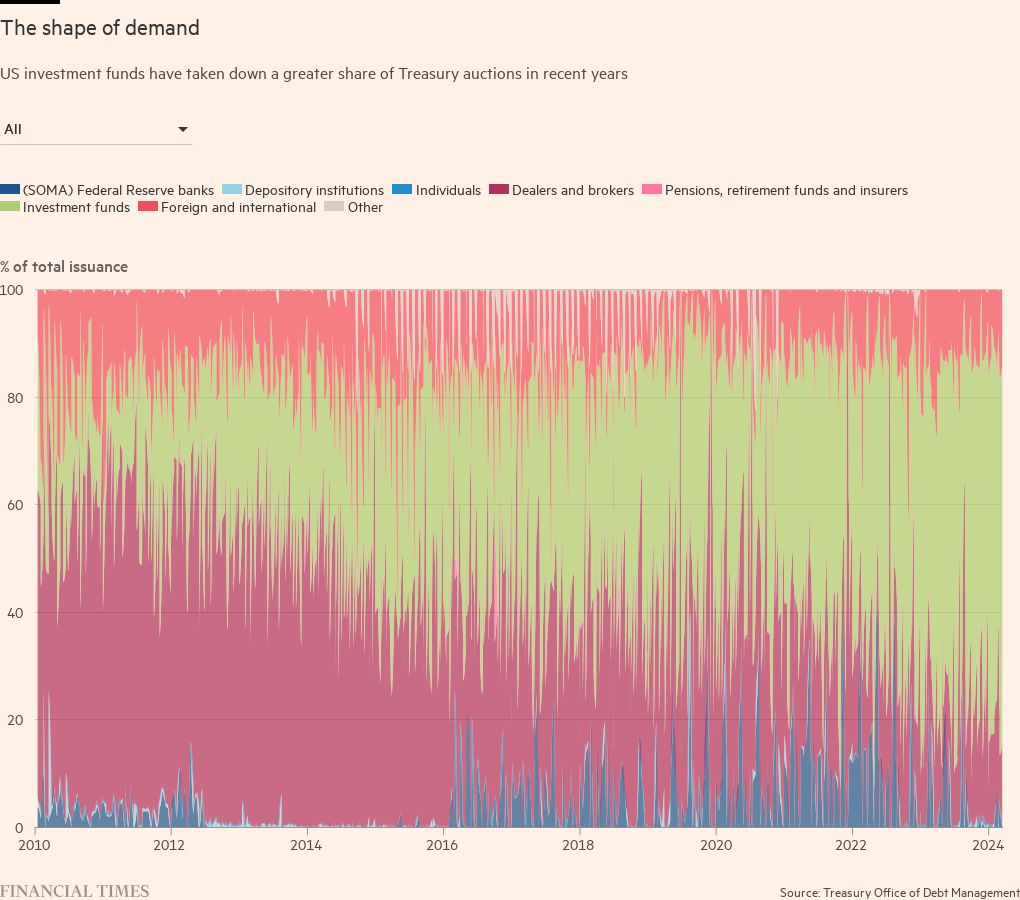

But twice a month, the US Treasury releases data showing categories of investors who bought at auction. And investment funds increasingly dominate.

You can see the breakdown over time here:

It’s tough to see the individual bidders, but they have been buying more; the increase has been especially notable in bills, which aren’t included in the Treasury data above.

Beyond that, investment funds have taken down a whole ton of extra paper as US rates have climbed in the past few years.

And foreign bidders have started to step in again as the Fed steps back from bond purchases. Those purchases aren’t active quantitative easing, as that happens in secondary markets, but replacing some of bonds on their balance sheet that are maturing. (Unlike the BoE, the Fed isn’t actively selling paper to shrink its balance sheet, but just buying fewer bonds at auction to replace those that are maturing.)

OK, so all of this makes sense. But I still don’t know why markets sold off last year!

Whoops, you’re right! Sorry about that.

The big issue here is the ongoing shift from short-term Treasury bills — in 2021 the US issued the most since Covid-19 relief to finance legislation like the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the CHIPS Act, etc — into notes and bonds, meaning longer-term debt that pays regular coupons.

Last year the Treasury Department started on a “terming out” path, and did it kind of aggressively. Like I mentioned earlier, long-dated Treasuries sold off last summer in part because of the sheer size of auctions of Treasury notes and bonds. Plus usual stuff like worries about inflation and higher interest rates etc, which is what mainly pushed up yields in 2022 as well.

Why make the change at all if it’s going to freak markets out like that?

Well, it’s usually pretty helpful to lock in longer-term financing, just for predictability reasons. And right now the yield curve is inverted, so longer-term borrowing is actually a bit cheaper than short-term financing — assuming you’re rolling over the debt for the same period of time.

Bills are more liquid and there’s been an absolute ton of demand; you know how everyone has been moving cash out of their bank accounts and into money-market funds?

That’s on my list of things to do.

Well, money-market funds are really big buyers of Treasury bills. And because there’s been so much demand for money-market funds, there’s also been lots of demand for bills.

What’s interesting is that the biggest risk of buying longer-term bonds seems to be past us . . . they usually experience the biggest losses when the Fed raises rates. The Fed is expected to cut this year, but the sheer supply of longer-term notes and bonds surprised markets last year.

In general, though, the Treasury’s debt-management moves are pretty clearly telegraphed ahead of time. Officials were able to reverse last year’s sell-off by giving a date when they would stop increasing the size of note and bond auctions.

Ah, I see. You know, it’s kind of wild that we have this whole Byzantine process for auctions that aren’t even allowed to fail.

I know, right?!

The funny thing is that failed government auctions aren’t always world-ending events. Germany’s bond auctions failed multiple times during the eurozone crisis in 2011. Sure, the eurozone is still a bit of a mess, but not in crisis, and Germany is fine.

You could argue that, when it comes to US Treasury auctions, primary dealers are glorified middlemen who give the appearance of private-market sales, without the Treasury actually having to risk any of the consequences of private-market sales . . . I’d say Cold War propaganda is a hell of a drug, but a broader look at history shows US policy has almost always been that way.

To be fair, big companies with investment-grade ratings haven’t had any trouble selling bonds lately, either. But there’s always some chance that the market will freeze up when it’s time to borrow. That’s a pretty big risk, especially if the Fed isn’t willing to step in and buy bonds the way it did during Covid-19.

That risk just doesn’t exist for Treasuries.

Well that’s comforting at least.

Yeah, you should be able to use that TreasuryDirect account without fear for a while still.

Comments