European companies can close the valuation gap

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is European portfolio strategist at Goldman Sachs

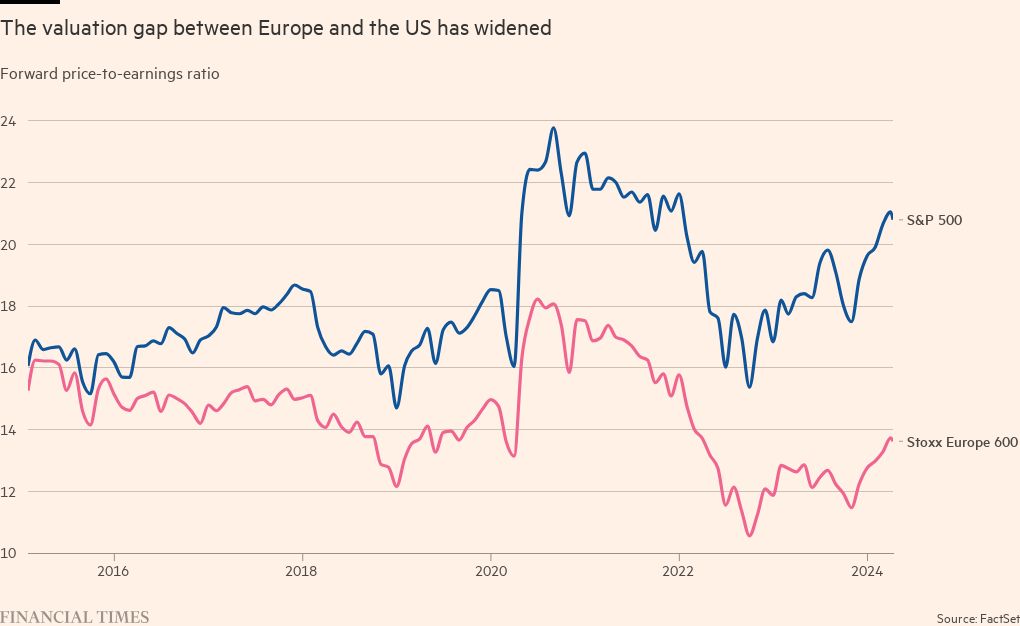

After a decade of stunning performance, outshining Europe and the rest of the world, the US equity market trades on a price/earnings ratio of more than 21 times. By contrast Europe trades on just 14 times and the UK is closer to 12. Of course, much of this valuation gap is a function of growth and sectoral differences. But not all of it. If we take companies with similar growth prospects, the US-listed stocks usually trade at a premium to Europe-listed peers. We also find that every single sector in Europe currently trades at a bigger discount to the US than they have in the past.

Certainly the valuation gap is a function of things outside the control of management teams. The war in Ukraine and the relative lack of energy independence have made Europe riskier for investors. European companies also tend to be more exposed to China, which is riskier than it was five years ago.

So what are the options for executives of European companies? They could de-risk their exposure, for example moving more of their business to the US. We have certainly seen this happen. European listed companies have about one-third of their assets in the US, up from 18 per cent a decade ago. In contrast, the march of investment towards China has largely halted.

Another possibility for managements is to buy back their own stock if they view it as undervalued. We see this happening especially among energy and financial stocks and we are not surprised. A common complaint about Europe is the lack of an equity culture. US households on average have roughly 30 per cent of their financial assets in the stock market compared with 10 per cent for European households, who prefer bank deposits, bonds and real estate investments.

Arguably, if capital is global this shouldn’t matter one iota. The shareholder rosters of the biggest European companies show they are largely held by international investors. But we think this lack of domestic interest in stocks does mean European citizens have less of a stake in equities and smaller caps have a lack of dedicated local buyers, while governments are more likely to regulate or tax than to support growth.

To change this, European companies themselves must invest in growth. US corporates spend roughly twice what European companies do on capex and R&D (as a share of cash flow). On the economic level much of the weakness in European productivity growth is a function of lack of investment and weak infrastructure. Greater corporate investment would benefit shareholders, employees and ultimately boost economies. That said, a lot of potential investment “leaks” out of Europe to places where subsidies or lower tax regimes make it more attractive.

There are other more direct solutions, such as relisting in the US. But this will only ever be applicable to those European companies with large US businesses, or in specific areas — such as biotech — where there is more analyst coverage in the US. Another possibility is for companies to spin off part of their business to list in the US. Again, this is only applicable to a few and might reduce the liquidity of a company’s main European listing. We increasingly hear from US investors that illiquidity is a factor that detracts from the appeal of European equities.

Going private is another option. Private European companies enjoy a higher valuation and a lower gap compared with those in the US. But this will again only be possible for a few companies and the valuation premium on private assets may simply reflect a lack of transactions rather than a genuine mismatch. Finally, M&A is an obvious catalyst to help push up European valuations, especially for mid and small caps. We have seen the beginnings of this already, but in our view more confidence in the interest rate outlook is needed to ensure it continues.

Ultimately, we think the valuation gap is likely to be here to stay. But there is scope for it to narrow. Better economic growth in Europe as manufacturing recovers from the doldrums and a focus by managements — but more importantly European politicians — on investment for growth and security (for example, in artificial intelligence, renewables and defence) are crucial. And in sectors where growth is lacking, buying back shares can be the right strategy; it’s a good sign that European managements are embracing this.

Investors themselves are increasingly concerned about the dominance of the megacap US tech stocks in their portfolios — finding interesting alternatives is moving up their agenda. Europe has value, it just needs to show it can deliver some growth.

Comments