Sleep deprivation can hit companies’ bottom lines

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The corporate world is full of stories of employees shunning sleep and working into the night.

In Japan, which is known for its pervasive corporate culture, a recent government survey revealed a fifth of companies had employees who were clocking more than 80 hours’ overtime a month. It also has been well reported that investment banking interns and juniors globally are working punishingly long hours .

But internet connectivity means increasing numbers of employees from all kinds of companies across the globe continue to work long hours after they have left the office. Two years ago, Jeff Bezos, chief executive of Amazon, was quick to say that he could not “recognise” anecdotes in a New York Times report which revealed, among other things, that Amazon staff were receiving work emails after midnight followed by text messages asking them why they had not been answered. The company declined to comment on the issue for this article.

Regardless of whether companies themselves are to blame, research shows workers who sleep less than six hours a night are less productive than people who sleep between seven and nine hours, according to research institute Rand Europe. In the US, sleep deprivation causes the loss of about 1.2m working days every year resulting in financial losses of up to $411bn a year (2.3 per cent of GDP), Rand Europe estimates.

“Many people feel they need to bust a gut every minute of the day fuelled on caffeine and sugar but as a result suffer from insomnia, stress and anxiety and struggle to sleep at night,” says sleep coach Nick Littlehales, author of Sleep: The Myth of 8 Hours, published last year. “You can’t just take some sleeping tablets before you go to bed and expect to force yourself into having a good quality sleep.”

Mr Littlehales, who has worked as a sleep coach for Premier League football teams such as Manchester United and for elite athletes including British Olympians, says he increasingly advises corporate clients. “A number of companies have been in touch to try and find a way to educate their employees,” he says. “Sleep deprivation in the workplace has become more of a concern.”

“How well you sleep at night depends on what you do throughout the day from the point of waking onwards,” says Mr Littlehales, whose book seeks to challenge some of the received wisdom about snoozing. “The idea that we should sleep in one eight-hour chunk is a relatively modern concept that gained currency with the invention of the lightbulb,” he says, pointing out that for most of human evolution we have slept more often and in shorter periods.

Mr Littlehales believes we sleep in 90-minute cycles — from dozing off, through light sleep, deep sleep, to the Rapid Eye Movement dream stage, to waking up and falling back to sleep again — and says we should aim to achieve an optimum number of cycles a night (for the average person 35 cycles per week is ideal). By viewing our sleep time as flexible, he says, we should not become overly worried by the occasional bad night.

In his consultations, Mr Littlehales advises staff to leave their desks and take short breaks every 90 minutes to aid mental and physical recovery from their work so they sleep better at night. He suggests redesigns of office space to improve workers’ access to natural light and recommends the use of daylight simulator lamps, which emit a bright flicker-free light close to natural sunlight, for use in the winter.

He also encourages companies to allow staff to take occasional short naps in the office. “After we’ve been awake for a certain amount of time we get to a point where we need to take a rest to boost alertness and improve performance,” he says. “If you show staff how they can nap naturally it can bring big benefits to your company.”

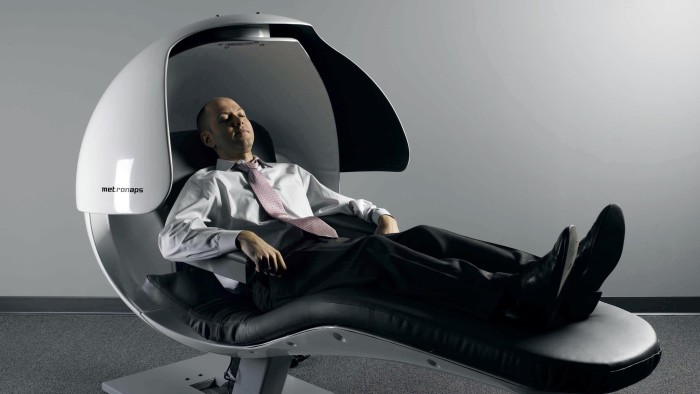

In response to advice such as Mr Littlehales’, a number of US companies have introduced on-site napping including Google — which has installed futuristic-looking sleep pods in its offices — Nike and Ben & Jerry’s.

Accountancy firm PwC, meanwhile, has introduced in-house programmes to teach staff good sleep practices. “The impact of sleep problems are often underestimated,” says PwC’s mental health leader Beth Taylor. “But apart from doing the right thing by our staff, there’s a hard commercial edge here — sleep is fundamental to performance.”

Comments