FTSE 100 falls flat as UK misses global stock rally

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

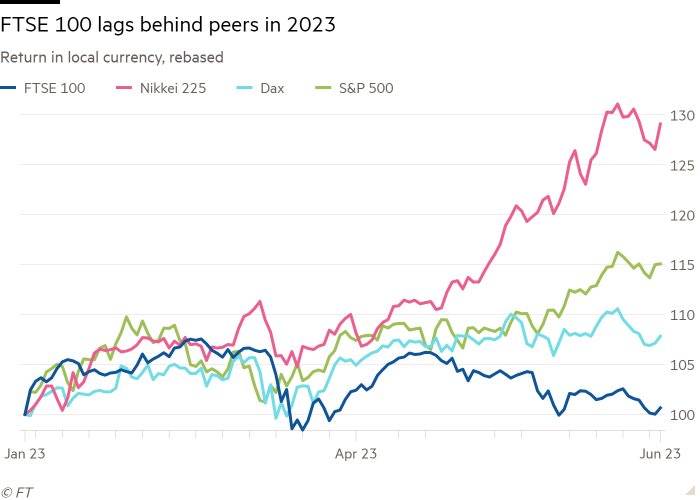

The UK has missed out on a global stock market rally so far in 2023 as the Bank of England’s rush to raise interest rates and falling oil prices hold back the FTSE 100.

London’s main benchmark has lagged well behind other big developed market indices, up less than 0.5 per cent from the level at which it finished 2022 by Thursday’s close, having fallen 2 per cent this quarter. The latest setback for a market that has long been out of favour with investors at home and abroad has dashed hopes that last year’s relative resilience heralded the start of a longer period of catch-up for the FTSE.

Rich in oil majors and other cash-generative value stocks but lacking large technology groups able to benefit from the recent hype around artificial intelligence, the UK makes for a relatively hard sell, analysts say. Meanwhile, relatively turbulent politics and uniquely stubborn inflation act as further deterrents to international investors.

Weak oil prices, rising rates and doubts over the BoE’s ability to rein in inflation have all contributed to the FTSE “putting up such a pedestrian show”, said Russ Mould, investment director at AJ Bell. “There’s not much tech or AI hoopla to be had,” he said.

Indices in Europe and the US have fared far better. France’s Cac 40 is up 12 per cent for the year, powered by a rally in luxury goods companies, while Germany’s Dax has gained 14 per cent. In the US, gains for Big Tech have pushed the top-heavy S&P 500 14 per cent higher. Japan’s Topix has surged to a 33-year high, as investors have looked to gain exposure to Chinese growth while minimising geopolitical risk.

Investors who in the past might have been attracted by the market’s chunky dividend payments may have had their heads turned by rising yields on lower-risk government bonds and the high returns offered by money market funds in the US and the UK, Mould said. The yield on UK two-year government bonds is 5.1 per cent, compared with a dividend yield of 4.3 per cent on the FTSE 100.

The FTSE’s glut of interest-rate sensitive housebuilders, banks, insurers and utility groups has meanwhile compounded the market’s vulnerability to higher rates. The energy and mining-heavy index has also been hit by falling commodity prices, with miners Fresnillo, Anglo American and Glencore among the FTSE’s worst performers this year.

Many investors have headed for the exit. Funds focusing on UK equities have experienced outflows equivalent to roughly 6 per cent of their total assets since the start of the year, according to calculations by Barclays using EPFR figures. Outflows have totalled less than 1 per cent of assets in the US, Japan and the rest of Europe.

The BoE’s struggle to tame inflation has also been a headwind. While rising interest rates battered stocks around the world last year, markets in Europe and the US have recovered as inflation recedes from its peak.

But rising prices have proved tougher to curb in the UK, forcing a bigger than anticipated rate rise from the BoE last week. Markets now expect UK rates to rise above 6 per cent by the end of the year, higher than borrowing costs are set to climb in other developed economies.

The BoE’s relative hawkishness has, at least until recently, boosted the pound: sterling is the best-performing developed market currency year-to-date. Sterling was also helped by meagre but steady economic growth and UK fiscal policy having regained credibility in the eyes of investors following former prime minister Liz Truss’s shortlived tenure last year. That is bad news for the FTSE, whose companies earn roughly 75 per cent of revenue overseas and therefore suffer a hit in sterling terms when the currency gains.

The strength of sterling means that the FTSE’s performance has been better in foreign currency terms, although domestic investors have suffered the poorest returns in the developed world.

Some analysts point out that recent cracks in sterling’s strength could actually provide a glimmer of hope for UK equities. Analysts at JPMorgan said it was “notable . . . that [the pound] did not broadly outperform” following the BoE’s surprise 0.5 percentage point rate rise last week, suggesting that the currency is becoming less responsive to moves in short-term rates and increasingly sensitive to concerns of an impending economic downturn and the health of the UK’s ailing housing market.

JPMorgan expects the pound to underperform, helping the index rise roughly 9 per cent to 8,150 — a record high — by the end of the year.

Others are less hopeful about an end to the FTSE’s long-term woes. “Despite seeing historic outflows over the past year, UK equities, and domestic-exposed plays in particular, remain out of favour,” said analysts at Barclays. “With no easy way out the stagflation quagmire and no apparent positive catalysts visible near term, the ostracism by investors may persist for now.”

Comments