John Gapper

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Three o’clock in the morning and a green sign looms above the highway: Weapons/Explosives Not Allowed. Two soldiers stand at a checkpoint, semi-automatic rifles slung on their shoulders. They flag down our car and take my passport. My family sits in the back, and I wonder: is this the wisest holiday destination?

When my wife Rosie Dastgir, whose father was Pakistani, was invited to the Lahore Literary Festival, it turned out to be half-term week. We could make a family trip to where our daughters’ grandfather was born, we realised. It sounded like fun. Now, just after arriving in the night from Dubai, it does not feel like that.

Eleven police have been killed in a suicide bomb attack in Karachi and talks between Nawaz Sharif’s government and the Pakistani Taliban are suspended when the latter execute 23 frontier troops. The UK Foreign Office notes “a high threat from terrorism, kidnap and sectarian violence throughout Pakistan”.

But this is Lahore, not Peshawar or even Islamabad. It is the capital and cultural centre of Punjab, where red sandstone buildings such as the Lahore Museum are dotted along wide avenues. Rudyard Kipling’s Kim sat astride the Zamzama cannon outside the museum, and we are staying at the Lahore Gymkhana Club, where you can eat a club sandwich with HP Sauce while watching the golfers.

As the week passes, we relax. Lahore is a friendly city and the security is more dutiful than urgent. In fact, it would help if the police took it more seriously – beeping scanners are ignored and they glance only cursorily into cars.

…

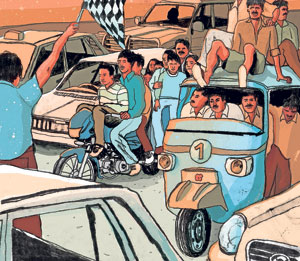

The clear and present danger is the traffic itself. At a rooftop restaurant by the magnificent 17th-century Badshahi Mosque, we can see smog sitting on the city. Kim took trams and trains with his Buddhist lama but public transport has been replaced by a fuming jam of motorcycles, cars, auto-rickshaws and so-called qingqis.

The rickshaws represent the old Lahore, thronging the stately parts of the city by the governor’s mansion. They are small-wheeled, steel-framed and fuelled by canisters of compressed natural gas. Riding beneath the canvas roof is smelly, noisy, and bumpy – like being in a dinghy on choppy seas – but exhilarating. The upstarts are qingqis – motorcycles with a passenger frame welded to the back, like brightly painted centaurs. They zoom around the old city, piled high with passengers, like racy minibuses. They are incredibly unsafe: corner at speed and the whole thing topples; any collision risks carnage. The qingqis (the name comes from a Chinese brand) seem to be supplanting rickshaws and there is talk of an amnesty, under which qingqi drivers could swap their steeds for rickshaws. But, so far, the bad is driving out the good.

As we tour Lahore, we marvel at the squish of humanity on the roads. It is common for a family of three or four to ride on a motorcycle, one child propped by the handlebars, and I see a qingqi carrying 11 souls. One local tells me she witnessed five men sitting in line on a motorcycle, with a sixth on their shoulders.

…

Rickshaw versus qingqi is one of Lahore’s cultural and economic divides. Another is language. Punjabi is the mother tongue and Urdu is the language of literature and state education, prescribed by British officers in 1874. English is, however, rising. The private schools that compete with Urdu language state schools use an English curriculum, with Urdu only as a language option. The children of the elite study in English and many then study at universities in the US, UK, Canada and Australia. Increasingly, young people speak some Urdu but cannot read the characters.

The new wave of Pakistani novelists, such as Mohsin Hamid, Mohammed Hanif and Kamila Shamsie, all write in English rather than Urdu. Urdu novelists such as 90-year-old Intizar Hussain, a finalist for the 2013 Man Booker International Prize, are the elderly champions of an ageing language.

Some feel sore about that, as becomes clear at an event for my wife’s novel, thrown by Mazhar ul Islam, an Urdu folklorist and writer. Mustansar Hussain Tarar, Urdu writer and columnist, talks of the “VIP treatment” given to younger English language writers. This division is exacerbated by an essentialist tussle over whether Pakistani writers who live abroad are really Pakistani writers. Both Hanif and Hamid have moved back to Pakistan after spells in the UK and US. Shamsie, who was brought up in Karachi but lives in London, responds that nobody questioned whether James Joyce, who lived in Paris, was an Irish writer.

…

Book festivals are springing up all over the subcontinent, from Jaipur to Dhaka (and Karachi), but Lahore’s has its own spirit. The security at the Alhamra Arts Centre symbolises why this is more than a writing celebration. The festival, now in its second year, is an effort at creative resurgence in a city where many feel worn down by unstable government, army machinations, economic uncertainties and fears over the future.

The threat from the Taliban, who would have no truck with the festival, and especially not with women artists, adds to the piquancy. Although 270,000 people visit Pakistan from the UK each year, most have family links. This is a rare way to pull the international crowd to the city, rather than exporting talent.

At the opening ceremony, Ahmed Rashid, the commentator and FT contributor who is one of the organisers, talks of wanting to “restore Lahore as a showcase of the dream of what Pakistan was in 1947 [at partition from India] …Do not be afraid to be with us today because we are not afraid of what we are trying to do.”

Fakir Aijazuddin, a historian, compares it with the wartime concerts held at the National Gallery in London in the 1940s by its director Kenneth Clark, who was asked: “Why are you doing this when doomsday seems to be a few days away?” He replied: “Because I want to remind people that these are the values that we are defending.”

Inside the barricades, where rickshaws painted with peace signs rest on lawns, young people line up to hear new writers. Middle-aged city dwellers, born into a moderate, pluralistic society, worry about a generational shift towards Islamic puritanism but there is no sign of it here.

After I take part in one discussion panel, a bearded youth asks me to sign the book he is clutching. It is Thomas More’s Utopia.

John Gapper is an FT columnist and author of ‘A Fatal Debt’ (Duckworth)

Comments