The framing of the Fed call on rates is too narrow

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is president of Queens’ College, Cambridge, and an adviser to Allianz and Gramercy

The US Federal Reserve has three primary options for interest rates when its top policymaking committee meets this week. None of them is optimal, and the one that the Fed has guided the markets to expect could potentially be the least desirable. Furthermore, all three reflect broader challenges that require a significant supply-side improvement in the economy and institutional reforms.

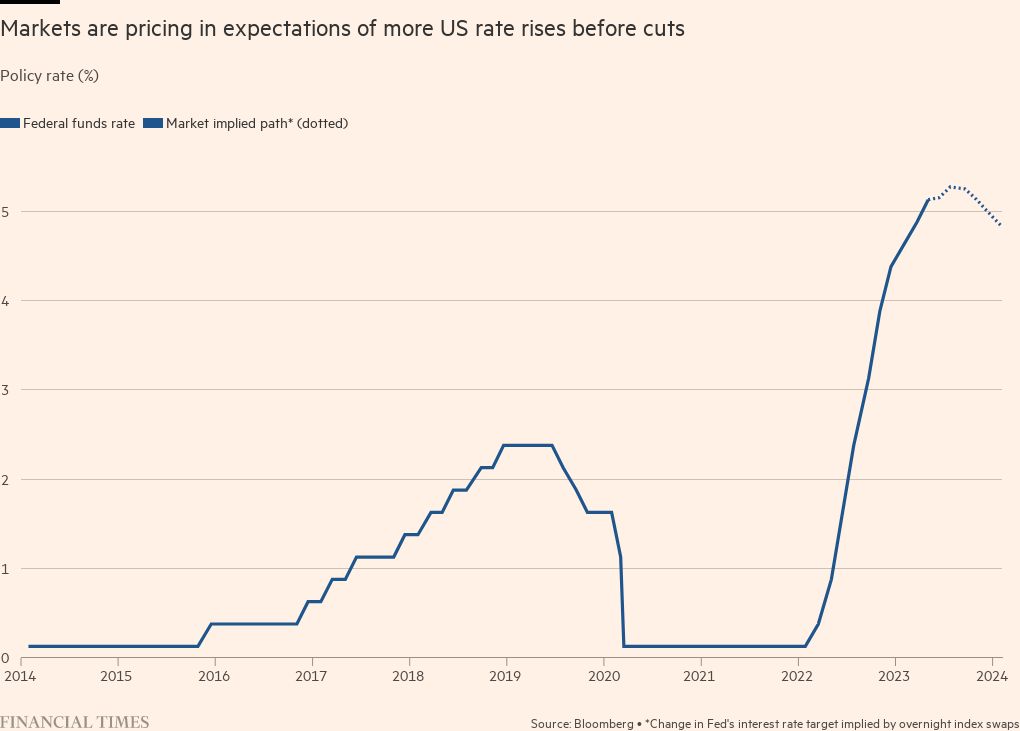

Based on guidance from a top Fed official, market expectations are that the central bank will “skip,” maintaining rates unchanged with an inclination to resuming hikes at the following meeting in July (similar to what Australia and Canada ended up doing).

This approach is seen as providing officials with more data to evaluate the effects of the most concentrated set of rate hikes in decades. As a result, the implied market probability of a June hike has fluctuated around 20-30 per cent in the last week, having previously peaked above 70 per cent before the latest guidance.

There are two issues with this approach. First, an additional month of data is unlikely to significantly enhance the Fed’s understanding of the effects of a policy tool that acts with variable lags. Second, recent data favours a hike for a central bank that has repeatedly insisted that it is “data dependent”.

No wonder some other Fed officials favour a hike this week. Their viewpoint points to the series of data surprises, including most recently higher job vacancies and robust monthly employment creation, as well as the lifting of immediate concerns regarding the US debt ceiling and banking instability.

But at least one Fed official believes that the May rate hike may have already erred on the side of being excessive as some forward indicators of economic activity have been signalling weakness. In this view, a pause would be followed by a rate cut as the next change.

Much has been written about why the Fed finds itself in this uncomfortable situation. The most commonly cited reason is that the Fed misjudged the inflation threat for most of 2021 and first quarter of 2022 before being forced into 10 successive rate hikes.

As a result, the Fed has experienced a significant erosion of its public standing and policy credibility. There has been a prolonged discrepancy between the Fed’s communication on the path of rates for 2023 and what markets expect. Moreover, a public disagreement has arisen between the Fed chair and the central bank’s staff regarding the likelihood of a recession. The Fed’s reputation has been further undermined by costly slips in bank supervision, lack of a suitable strategic policy framework, weak accountability, and susceptibility to groupthink.

Given the multiple causes, the Fed is unlikely to resolve its predicaments any time soon. Moreover, unless the CPI inflation data due out on Tuesday shows significant weakness, its proposed course of action — the “skip” — would end up as the muddled middle option, rendering future decisions even more challenging.

If the Fed is genuinely data dependent and truly committed to achieving its current inflation target of 2 per cent, it should raise rates by 0.25 percentage points and leave the door open for additional hikes. Recent data surprises, combined with the balance of risks associated with Fed’s policies, both suggest that this route is preferable to a “skip.”

However, if the Fed believes, as I do, that it is operating with an outdated inflation target due to significant changes on the supply side of the economy — and that the modification of the target requires a lengthy and delicate process — then it should opt for a pause with an inclination to cut when appropriate.

This would allow the effects of the previous rate hikes to permeate through the economy, and reduce the likelihood of both undue damage to economic growth and unsettling financial instability.

Recall that the Fed’s policy mistakes over the past two years and its institutional weaknesses are not the only factors that have undermined its effectiveness. Changing patterns of globalisation, the restructuring of corporate supply chains, the energy transition, and labour market mismatches all indicate that the Fed is operating with an inflation target that is probably too low for durable economic wellbeing.

In this context, the current framing of the policy debate is overly narrow. It is more likely to confuse matters than to stimulate the type of deliberations that can rebuild the foundation for the Fed to contribute to high inclusive growth and financial stability.

Comments