Charlotte Salomon at the Jewish Museum London — Simon Schama on a modernist masterpiece

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Caveat visitor! This is no routine art show. Once you have been exposed to Charlotte Salomon’s shattering and profound Life? or Theatre? — which is by turns horrifying, ecstatic and tragic — her colour-drenched paintings and the family tragedy that they dramatise will stay with you forever.

Alone in a Côte d’Azur hotel room in the winter of 1941-42, scarcely stopping for food or drink, the German artist painted nightmares, suicides, erotic fantasies and heartbreakingly unrequited love to the drumbeat of the Nazi ascendancy. By the summer of 1942 she had completed 1,300 gouaches, as well as texts that were either semi-transparent papers overlaid on the sheets or painted directly on to the paper. She then edited the vast mass of words and images down to 769 — all part of a single, narrative work. From these, London’s Jewish Museum has made a generous, thrilling selection of 236, more than enough for deep immersion in the Singspiel (as she called it, the musical element crucial).

It is a Jewish story, but also a poignant document of the human condition — especially of women enduring extreme stress, from within individual minds or from the tortured madness into which the world descended before the war. Salomon’s family history is enacted on the rim of an abyss and, too often, sinks into its fathomless darkness. Her mother committed suicide when she was eight years old; on the same side of the family there were nine more suicides, including an 18-year-old aunt who drowned herself four years before Charlotte’s birth and for whom she was named, and her maternal grandmother whose leap from a window she witnessed.

The Salomons were secular, well-off Berlin Jews. Charlotte’s father Albert had served in the first world war, was briefly interned in Sachsenhausen concentration camp by the Nazi regime, then worked in a Jewish hospital until he and his second wife, singer Paula Lindberg (née Levy), went to Amsterdam in 1939. Charlotte was sent to live with her grandparents in the south of France. With the German occupation in 1943, Charlotte, five months pregnant, along with her husband (also a German refugee), were deported to Auschwitz, where she was immediately murdered on October 10. She was 26 years old, a prodigious talent snuffed out, but not before she had created a masterpiece of 20th-century modernist art.

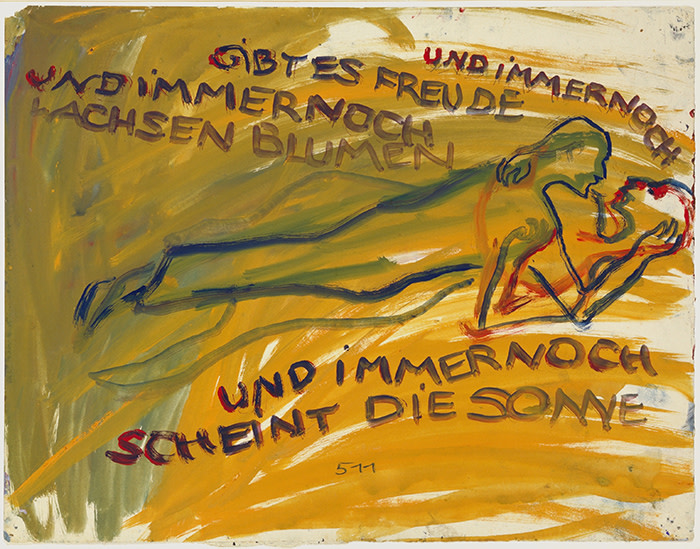

That is but the bare bones of the story. Because she was a casualty of Nazi mass murder, and because Life? or Theatre? presents itself as her life story, the temptation is to pigeonhole the huge, complex work as “Holocaust art”: a kind of illustrated Anne Frank. But this is to sell short its distinctiveness as an experimental modernist epic. The piece is a virtuoso Gesamtkunstwerk; flooded with writing, enigmatic or emotionally expressive, winding across or down the sheet; sometimes raising its voice from a strangled cry embodied in small insect-like trail-marks, the letters at other times expanding gigantically to crowd the space in bursts of howling anguish.

The theatricality alluded to in the title, with its teasing question marks, is not gratuitous. The cast of characters, all real figures in Salomon’s life, are given Singspiel names as if scripted to perform. Her stepmother, the contralto Paula Lindberg, becomes Paulinka Bimbam; the singing teacher with whom Charlotte falls in love was in fact the philosophising Alfred Wolfsohn but appears here as bespectacled, curly-haired Amadeus Daberlohn (skint Mozart).

The first “act” — called “Prelude”, beginning with the drowned aunt, scenes of Berlin street and home life, the courtship and marriage of her mother and father — owes a lot to 1930s cinema; both expressionist and surreal, spooling across the sheet like a celluloid strip or, as with their apartment, seen top-shot, the planes of the rooms scrambled, off-kilter, the texts laid in like a sound strip.

Accordingly, these early scenes have a racy, animated character, figures in family gatherings or speeding through the frame. A holiday trip to the Bavarian mountains has the adult Salomon recovering a childhood idyll through artless classroom drawing: meadows bright with wildflowers, swaying conical hills and toy trains puffing through the frame: innocence unclouded by tragic knowledge. There are intimations: in a Chagall-like scene (above), mother in bed with daughter, asks her whether it wouldn’t be nice if Mummy became an angel and is seen ascending to a white-bearded welcome from a deity looking not unlike grandpa.

The format takes a sharp turn when Salomon’s mother sinks into depression. The genre scenes of family and street life close in to stationary portraits of faces and bodies that fill the picture space. Most astonishing is her mother, upside-down in death, as if flying to her doom, a bloom of blood pouring from her head, one broken leg protruding obscenely from her rucked-up nightgown, the whole body torqued like an agonised version of one of Michelangelo’s figures on the Sistine ceiling.

This is followed by images of family trauma: her father holding big hands to his tormented head; the grandmother Marianne, bereft of both her daughters, hunched in a dark block of despair; Salomon herself sitting on the rim of a bathtub facing a toilet seat and its suddenly sinister pull-chain. For years the artist was led to believe that her mother had died from influenza. Now that she re-enacts the truth, she adds the most laconic of postmortems: “Franziska died immediately, the apartment being on the third floor. There is nothing to be done about the tragedy.”

Five years later, her father remarries Paulinka: glamorously blonde and charismatic. Into the home also comes singing teacher Daberlohn, with whom the adolescent Salomon falls in love. A predictable emotional triangle develops; Paulinka alternately flirting with her musician pursuer and holding him at bay while he indulges Salomon’s passion in secret café conversations as he delivers gobbets of Nietzschean wisdom on art, death, song and redemption.

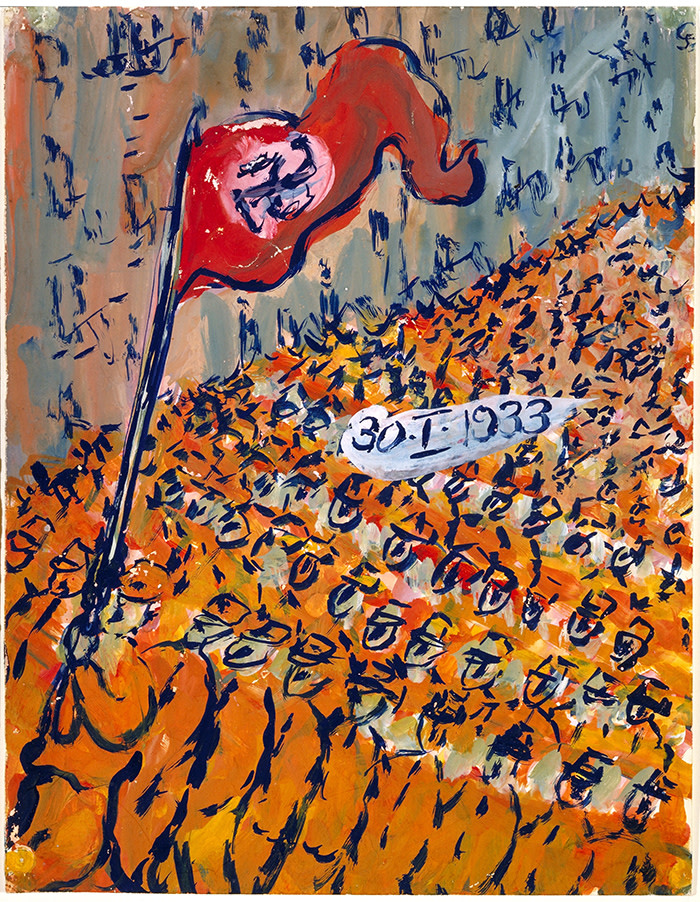

Beyond this domestic opera of sensual manoeuvre, Nazis parade through the streets; massed crowds roar their brutal acclaim. Paulinka sings “when thou art near, I go to my death with joy” while a storm of expressionist colour spatters the audience. Daberlohn departs; Salomon gives him her drawing of “Death and the Maiden”, which won the art school competition, though as a Jew (the only one in her class) she was precluded from receiving it. Images of sexual consummation, fantasies or memories pour forth: she and the skint Amadeus boating along in a stream of desire; coupling awkwardly on the beach. In an otherwise empty room painted in Van Gogh’s lurid yellow and sour green, Salomon sits on a closed suitcase while another gapes open on her bed. It is one of the great images of the Jewish tragedy.

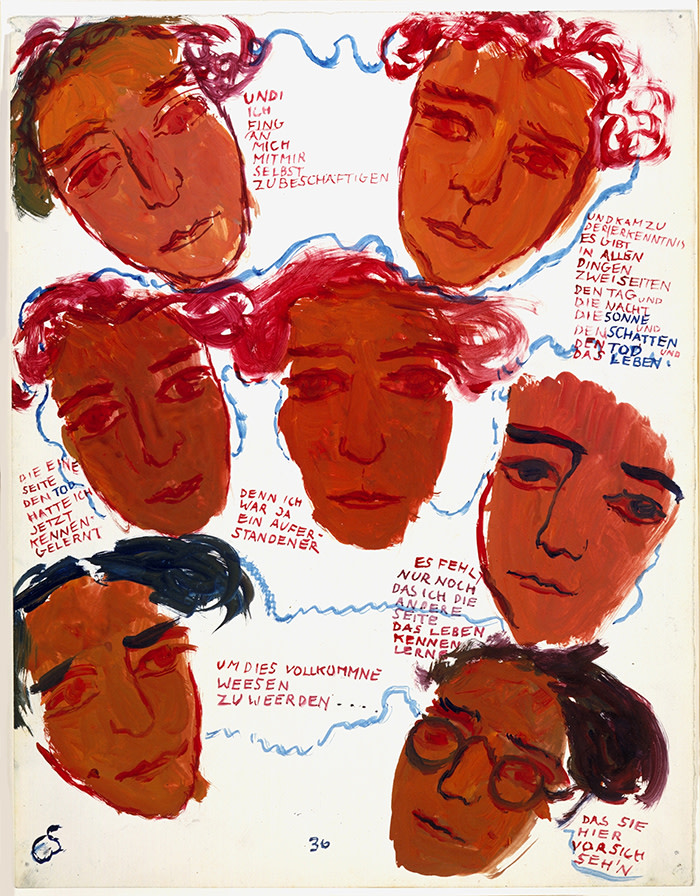

Deeper into the sunshine and the darkness she goes in an “Epilogue”, the fatal climax of the immense work. Salomon and her grandparents are lodged in a guesthouse. But the grandmother, Marianne, sucked into the vortex of depression that had already killed her daughters, tries and fails to hang herself — but then, despite Salomon’s intervention, succeeds in throwing herself to the street below. Over three pages of mask-like faces, her grandfather lays before her the whole epic story of the women’s self-destruction, suggesting at one point that Salomon might as well follow suit to “end the babble”.

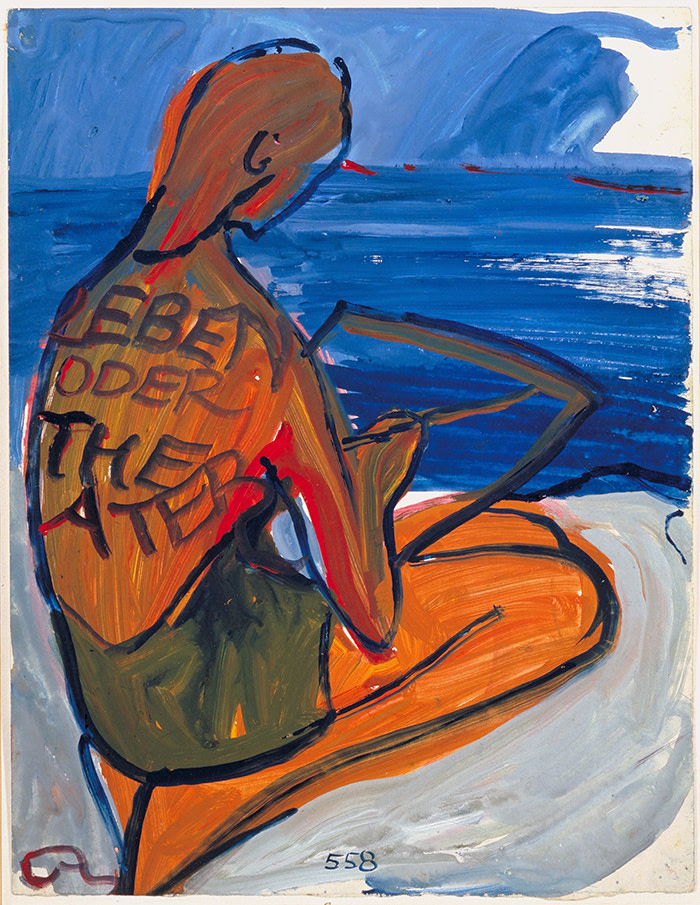

The final sheet, poignantly beautiful, is also a beginning. The artist sits beside the cobalt-blue Mediterranean, knees tucked under her, beginning to paint her story, its title painted in broad letters across her sun-tanned back. But the framed sheet is transparent, like the frames of windows against which many of the doomed figures populating her story set themselves.

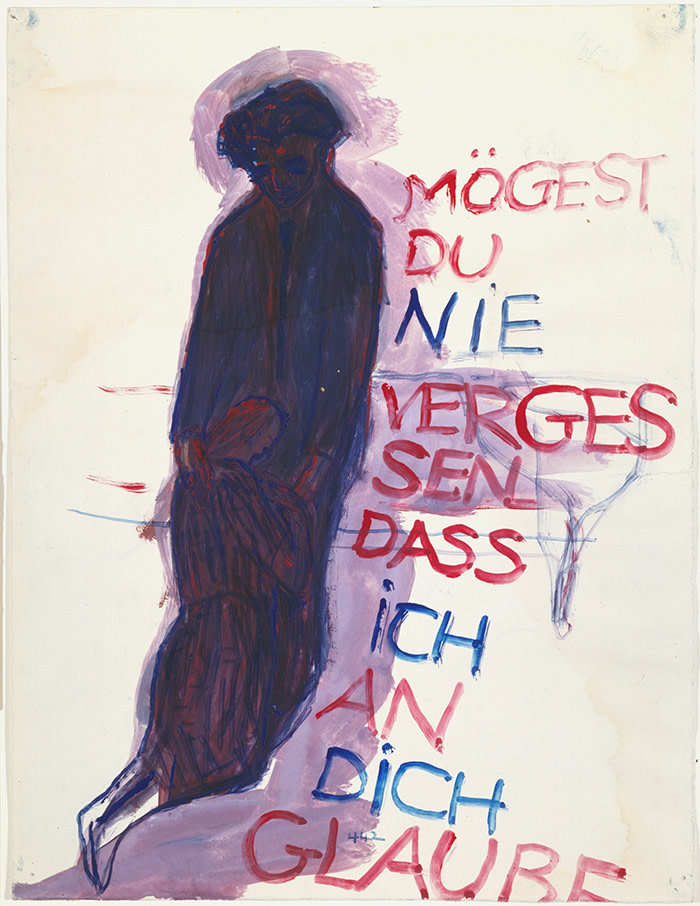

The idyll was provisional. Salomon would disappear up one of the chimneys of Auschwitz as smoke blown into its poisoned wind. But — and this is a whole other, miraculous story — her staggeringly beautiful masterwork would survive her. “I have set before you life and death, blessing and curse,” says Deuteronomy, “therefore choose life.” She did so, and was killed nonetheless. Yet her torn-up life persists forever in this extraordinary work.

To March 1, jewishmuseum.org.uk

Simon Schama is an FT contributing editor

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Listen and subscribe to Culture Call, a transatlantic conversation from the FT, at ft.com/culture-call or on Apple Podcasts

Comments